ConcinN, etal. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2021;31:12–39. doi:10.1136/ijgc-2020-002230

12

ESGO/ESTRO/ESP guidelines for the management

of patients with endometrialcarcinoma

Nicole Concin ,

1,2

Xavier Matias- Guiu,

3,4

Ignace Vergote,

5

David Cibula,

6

Mansoor Raza Mirza,

7

Simone Marnitz,

8

Jonathan Ledermann ,

9

Tjalling Bosse,

10

Cyrus Chargari,

11

Anna Fagotti,

12

Christina Fotopoulou

,

13

Antonio Gonzalez Martin,

14

Sigurd Lax,

15,16

Domenica Lorusso,

12

Christian Marth,

17

Philippe Morice,

18

Remi A Nout,

19

Dearbhaile O'Donnell,

20

Denis Querleu ,

12,21

Maria Rosaria Raspollini,

22

Jalid Sehouli,

23

Alina Sturdza,

24

Alexandra Taylor,

25

Anneke Westermann,

26

Pauline Wimberger,

27

Nicoletta Colombo,

28

François Planchamp,

29

Carien L Creutzberg

30

For numbered afliations see

end of article.

Correspondence to

Nicole Concin, Department of

Gynecology and Obstetrics,

Innsbruck Medical University,

Innsbruck 6020, Austria; nicole.

concin@ i- med. ac. at

For ‘Presented at statement’

see end of article.

Received 7 November 2020

Accepted 16 November 2020

Published Online First

18December2020

To cite: ConcinN,

Matias- GuiuX, VergoteI,

etal. Int J Gynecol Cancer

2021;31:12–39.

Joint statement

© IGCS and ESGO 2021. No

commercial re- use. See rights

and permissions. Published by

BMJ.

Original research

Editorials

Joint statement

Society statement

Meeting summary

Review articles

Consensus statement

Clinical trial

Case study

Video articles

Educational video

lecture

Corners of the world

Commentary

Letters

ijgc.bmj.com

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF

GYNECOLOGICAL CANCER

ABSTRACT

A European consensus conference on endometrial

carcinoma was held in 2014 to produce multi- disciplinary

evidence- based guidelines on selected questions.

Given the large body of literature on the management

of endometrial carcinoma published since 2014, the

European Society of Gynaecological Oncology (ESGO), the

European SocieTy for Radiotherapy and Oncology (ESTRO),

and the European Society of Pathology (ESP) jointly

decided to update these evidence- based guidelines and

to cover new topics in order to improve the quality of care

for women with endometrial carcinoma across Europe and

worldwide.

INTRODUCTION

Endometrial carcinoma is the most common gyneco-

logical cancer in Europe, with a 5- year prevalence of

34.7% (445 805 cases).

1

The estimated number of

new endometrial carcinoma cases in Europe in 2018

was 121 578 with 29 638 deaths, and the incidence

has been rising with aging and increased obesity of

the population. The EUROCARE-5 study, published in

2015, reported a 5- year relative survival of 76% for

European women diagnosed with endometrial carci-

noma in 2000–2007, ranging from 72.9% in Eastern

Europe to 83.2% in Northern Europe.

2

The observed

geographic difference might be partially attributable

to tangible differences in the prevalence of endome-

trioid sub- types among regions. Furthermore, differ-

ences in patient characteristics and histopathologic

features of the disease impact both on patient prog-

nosis and the recommended treatment approach.

A consensus conference including representa-

tion from the European Society of Medical Oncology

(ESMO), the European Society of Gynaecological

Oncology (ESGO), and the European SocieTy for

Radiotherapy and Oncology (ESTRO) was held in

2014 with the aim to produce multi- disciplinary

evidence- based guidelines on 12 selected questions

in order to complement the ESMO clinical practice

guidelines previously published.

3–6

ESGO, ESTRO,

and the European Society of Pathology (ESP) jointly

decided to update these evidence- based guidelines

and, moreover, to cover new topics in order to provide

comprehensive guidelines on all relevant issues of

diagnosis and treatment in endometrial carcinoma

in a multi- disciplinary setting. These guidelines

are intended for use by gynecological oncologists,

general gynecologists, surgeons, radiation oncolo-

gists, pathologists, medical and clinical oncologists,

radiologists, general practitioners, palliative care

teams, and allied health professionals.

RESPONSIBILITIES

These guidelines are a statement of evidence and

consensus of the authors regarding their views of

currently accepted approaches for the management

of patients with endometrial carcinoma. Any clinician

applying or consulting these guidelines is expected

to use independent medical judgment in the context

of individual clinical circumstances to determine any

patient’s care or treatment. These guidelines make no

warranties of any kind regarding their content, use, or

application, and the authors disclaim any responsi-

bility for their application or use in any way.

METHODS

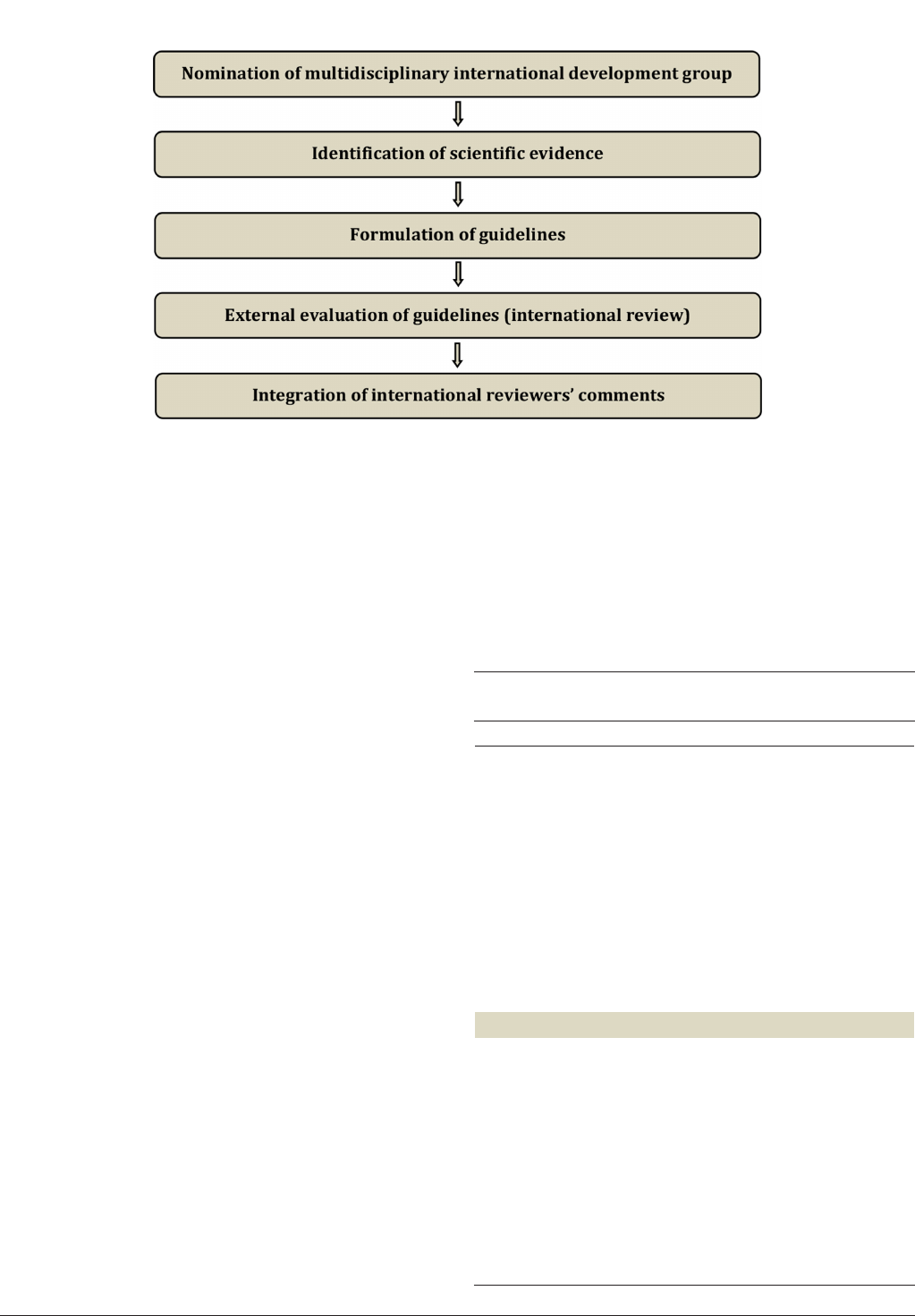

The guidelines were developed using a ve- step

process as dened by the ESGO Guideline Committee

(see Figure1). The strengths of the process include

creation of a multi- disciplinary international devel-

opment group, use of scientic evidence and inter-

national expert consensus to support the guidelines,

and use of an international external review process

(physicians and patients). This development process

involved three meetings of the international devel-

opment group chaired by Professor Nicole Concin

(Medical University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria/

Evangelische Kliniken Essen- Mitte, Essen, Germany,

for ESGO), Professor Carien L Creutzberg (Leiden

University Medical Center, Leiden, the Nether-

lands, for ESTRO), and Professor Xavier Matias- Guiu

(Department of Pathology, Hospital Universitari Arnau

de Vilanova and Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge,

on August 30, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://ijgc.bmj.com/Int J Gynecol Cancer: first published as 10.1136/ijgc-2020-002230 on 18 December 2020. Downloaded from

13

ConcinN, etal. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2021;31:12–39. doi:10.1136/ijgc-2020-002230

Joint statement

Irblleida, Idibell, Universities of Lleida and Barcelona, CIBERONC,

Spain, for ESP).

ESGO/ESTRO/ESP nominated practising clinicians who are

involved in the management of patients with endometrial carcinoma

and have demonstrated leadership in the clinical management of

patients through research, administrative responsibilities, and/or

committee membership to serve on the expert panel. The objective

was to assemble a multi- disciplinary panel and it was therefore

essential to include professionals from relevant disciplines (gyne-

cological oncology and gynecology, medical, clinical and radiation

oncology, pathology) to contribute to the validity and acceptability of

the guidelines. To ensure that the statements were evidence based,

the current literature was reviewed and critically appraised. A

systematic literature review of relevant studies published between

January 2014 and June 2019 was carried out using the MEDLINE

database (see online supplemental appendix 1). The literature

search was limited to publications in English. Priority was given to

high- quality systematic reviews, meta- analyses, and randomized

controlled trials, but studies of lower levels of evidence were also

evaluated. The search strategy excluded editorials, letters, and in

vitro studies. The reference list of each identied article was also

reviewed for other potentially relevant articles.

The development group developed guidelines for all the topics.

The guidelines were retained if they were supported by a suf-

ciently high level of scientic evidence and/or when a large

consensus among experts was obtained. An adapted version of the

'Infectious Diseases Society of America- United States Public Health

Service Grading System' was used to dene the level of evidence

and grade of recommendation for each of the recommendations

7

(see Table1). In the absence of any clear scientic evidence, judg-

ment was based on the professional experience and consensus of

the development group.

ESGO/ESTRO/ESP established a large multi- disciplinary panel

of practicing clinicians who provide care to patients with endo-

metrial carcinoma to act as independent expert reviewers for the

guidelines developed. These reviewers were selected according to

their expertise, had to be still involved in clinical practice, and were

from different European and non- European countries to ensure

global perspective. Patients with endometrial carcinoma were also

included. These independent reviewers were asked to evaluate

each recommendation according to its relevance and feasibility in

clinical practice (only physicians), so that comprehensive quantita-

tive and qualitative evaluations of the guidelines were completed.

Patients were asked to evaluate qualitatively each recommen-

dation (according to their experience, personal perceptions, etc).

Figure 1 Development process.

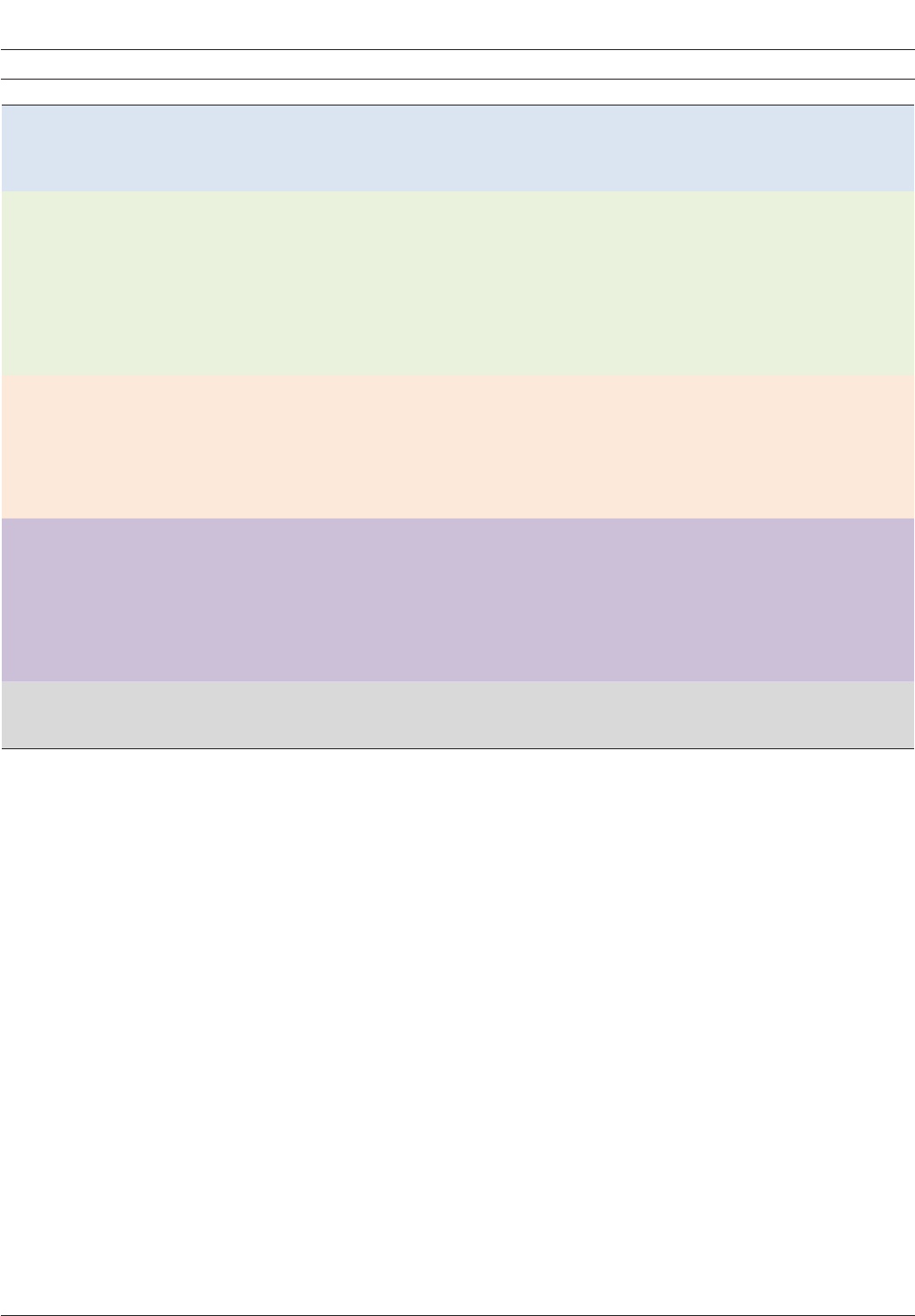

Table 1 Levels of evidence and grades of

recommendations

Levels of evidence

I Evidence from at least one large randomized

controlled trial of good methodological quality

(low potential for bias) or meta- analyses of well-

conducted randomized trials without heterogeneity

II Small randomized trials or large randomized trials

with a suspicion of bias (lower methodological

quality) or meta- analyses of such trials or of trials

with demonstrated heterogeneity

III Prospective cohort studies

IV Retrospective cohort studies or case–control studies

V Studies without control group, case reports, expert

opinions

Grades of recommendations

A Strong evidence for efcacy with a substantial clinical

benet, strongly recommended

B Strong or moderate evidence for efcacy but with a

limited clinical benet, generally recommended

C Insufcient evidence for efcacy or benet does not

outweigh the risk or the disadvantages (adverse

events, costs, etc), optional

D Moderate evidence against efcacy or for adverse

outcome, generally not recommended

E Strong evidence against efcacy or for adverse

outcome, never recommended

on August 30, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://ijgc.bmj.com/Int J Gynecol Cancer: first published as 10.1136/ijgc-2020-002230 on 18 December 2020. Downloaded from

14

ConcinN, etal. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2021;31:12–39. doi:10.1136/ijgc-2020-002230

Joint statement

Evaluations of the external reviewers (n=191) were pooled and

discussed by the international development group before nalising

the guidelines. The list of the 191 external reviewers is available in

online supplemental appendix 2.

GENERAL RECOMMENDATIONS

► Planning of staging and treatment should be made on a

multi- disciplinary basis (generally at a tumor board meeting,

composed according to local guidelines) and based on the

comprehensive and precise knowledge of prognostic and

predictive factors for outcome, morbidity, and quality of life (V,

A).

► Patients should be carefully counseled about the suggested

diagnostic and treatment plan and potential alternatives,

including risks and benets of all options (V, A).

► Treatment should be undertaken in a specialized center by a

dedicated team of specialists in the diagnosis and manage-

ment of gynecological cancers, especially in high- risk and/or

advanced stage disease (V, A).

IDENTIFICATION AND SURVEILLANCE OF WOMEN WITH A

PATHOGENIC GERMLINE VARIANT IN A LYNCH SYNDROME-

ASSOCIATED GENE

Approximately 3% of all endometrial carcinomas and about 10%

of mismatch repair decient (MMRd)/microsatellite unstable endo-

metrial carcinomas are causally related to germline mutations of

one of the MMR genes MLH1, PMS2, MSH2 and MSH6.

8

Testing

for MMR status/microsatellite instability (MSI) in endometrial carci-

noma patients has been shown to be relevant for four reasons: (1)

diagnostic, as MMRd/MSI is considered a marker for endometrioid-

type endometrial carcinoma; (2) pre- screening to identify patients at

higher risk for having Lynch syndrome; (3) prognostic, as identied

by The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA, see below for molecular clas-

sication); and (4) predictive for potential utility of immune check-

point inhibitor therapy. The International Society of Gynecological

Pathology (ISGyP) has recommended testing for MMR status/MSI in

all endometrial carcinoma samples, irrespective of age.

9

This has

also been recommended in other society statements and recom-

mendations, such as the Manchester International Consensus

Group recommendations, whenever resources are available.

10

The preferred approach (widely available and cost- effective) to

identifying patients with a higher chance of having Lynch syndrome

is by MMR- immunohistochemistry (IHC) on well preserved tumor

tissue. MMR- IHC is a reliable method to assess MMR status, and

in addition provides information on the altered gene/protein. ISGyP

guidelines therefore recommend MMR- IHC as the preferred test.

9

MMR- IHC consists of the assessment of the expression of four

MMR proteins (MLH1, PMS2, MSH6, and MSH2). A simplied two-

antibody (PMS2 and MSH6) approach has been proposed as a cost-

effective alternative.

11–13

This procedure still requires performing

MLH1 and MSH2 IHC in cases with any abnormal staining of PMS2

and/or MSH6. Molecular analyses for the microsatellite status

(MSI- test) are an alternative, but are more laborious, require non-

neoplastic tissue, are more expensive, and do not provide infor-

mation on the gene affected. For optimal pre- selection of patients

at risk for having Lynch syndrome, both approaches require the

analysis of MLH1 promoter methylation status in cases with loss of

MLH1/PMS2 expression. Testing for MMRd by IHC or MSI by PCR-

based methods does not allow direct identication of patients with

Lynch syndrome since MMRd/MSI is frequently due to sporadic

events such as bi- allelic somatic mutations or hypermethylation.

In the absence of hypermethylation, referral to genetic counseling

is recommended to evaluate the presence of a germline muta-

tion. When familial history is highly suspicious of Lynch syndrome,

genetic counseling is recommended independent of the MMR

status.

The cumulative incidences for cancer depend on the specic

mutation in women with Lynch sydrome. For endometrial carci-

noma, the cumulative incidences at 70 years are 34%, 51%,

49%, and 24% for MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2 mutation

carriers, respectively, and for ovarian cancer 11%, 15%, 0%,

and 0%, respectively.

14

Furthermore, the age of cancer onset in

Lynch syndrome varies among specic mutated genes and types

of mutations.

15

Ryan et al suggest gynecological surveillance to

be appropriate from age 30 years for those with MSH2 mutations,

from age 35 years for those with nontruncating MLH1 mutations,

and from age 40 years for those with MSH6 and truncating MLH1

mutations. Women with heterozygous PMS2 mutations do not

warrant gynecological surveillance because their absolute risk of

gynecological cancer is very low. As part of a retrospective study,

Lachiewicz et al reported a risk of any occult malignancy during

prophylactic surgery for women with Lynch syndrome or heredi-

tary non- polyposis colorectal cancer to be up to 17%.

16

Thus, these

patients should be counseled about the risk of detection of gyneco-

logical cancer at prophylactic surgery.

Recommendations

► To identify patients with Lynch syndrome and triage for germline

mutational analysis, MMR IHC (plus analysis of MLH1 promotor

methylation status in case of immunohistochemical loss of

MLH1/PMS2 expression) or MSI tests should be performed in

all endometrial carcinomas, irrespective of histologic subtype

of the tumor (III, B).

► Endometrial carcinoma patients identied as having an

increased risk of Lynch syndrome should be offered genetic

counseling (III, B).

► Surveillance for endometrial carcinoma in Lynch syndrome

mutation carriers should in general start at the age of 35 years;

however, individual factors need to be taken into consideration

(tailored surveillance programs). The decision on the starting

age of surveillance should integrate knowledge on the specic

mutation and history of onset of events in the family (IV, B).

► Surveillance of the endometrium by annual transvaginal ultra-

sound (TVUS) and annual or biennial biopsy until hysterectomy

should be considered in all Lynch syndrome mutation carriers

(IV, B).

► Hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo- oophorectomy to prevent

endometrial and ovarian cancer should be performed at the

completion of childbearing and preferably before the age of

40 years. All the pros and cons of prophylactic surgery must

be discussed including the risk of occult gynecological cancer

detection at prophylactic surgery. Estrogen replacement

therapy should be suggested if bilateral salpingo- oophorectomy

is performed in pre- menopausal women (IV, B).

on August 30, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://ijgc.bmj.com/Int J Gynecol Cancer: first published as 10.1136/ijgc-2020-002230 on 18 December 2020. Downloaded from

15

ConcinN, etal. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2021;31:12–39. doi:10.1136/ijgc-2020-002230

Joint statement

MOLECULAR MARKERS FOR ENDOMETRIAL CARCINOMA

DIAGNOSIS AND AS DETERMINANTS FOR TREATMENT

DECISIONS

Different types of endometrial carcinoma have specic histolog-

ical and molecular features, precursor lesions and natural histo-

ries. Conventional pathologic analysis remains an important tool

for tumor stratication, but suffers from inter- observer varia-

tion. Different groups have applied a diagnostic algorithm using

three immunohistochemical markers (p53, MSH6 and PMS2)

and one molecular test (mutation analysis of the exonuclease

domain of POLE) to identify prognostic groups analogous to the

TCGA molecular- based classication.

17–21

The feasibility of this

approach was conrmed by a large number of publications that

have all consistently reported prognostic relevance particularly in

high- grade and high- risk tumors in several independent cohorts

and prospective clinical trials.

22

To apply this molecular classica-

tion, all these diagnostic tests need to be performed. Performing

one of the surrogate marker tests in isolation is insufcient, as a

combination of positive tests can occur in approximatively 5% of

all carcinomas. The diagnostic algorithm to classify these so- called

'multiple classiers' has been described recently.

23 24

In addition,

endometrial carcinoma should only be classied as POLE- mutated

(POLEmut) when pathogenic variants of POLE are identied in the

gene’s exonuclease domain.

25 26

This surrogate marker approach to the molecular- based classi-

cation has been demonstrated to be prognostically informative in

low-, intermediate-, and high- risk endometrial carcinoma. Smaller

studies showed that the molecular classication is also applicable

to non- endometrioid tumors including serous, clear cell, undiffer-

entiated carcinomas, and uterine carcinosarcomas. For adjuvant

treatment recommendations, the molecular classication seems to

be particularly relevant in the context of high- grade and/or high- risk

endometrial carcinomas. Application of the molecular classication

in high- grade and/or high- risk endometrial carcinomas shows that

there is a group of patients with an excellent prognosis—that is,

the POLEmut tumors—and a group with a poor prognosis—that is,

the p53- abnormal (p53abn) tumors. Endometrial carcinomas with

MMRd or non- specic molecular prole (NSMP) have an interme-

diate prognosis. However, the molecular surrogate is not perfect.

Immunohistochemical demonstration of p53abn is a good but not

perfect surrogate of TP53 mutation. Furthermore, a small propor-

tion of high copy number tumors do not show TP53 mutations. To

minimize these limitations, an integrated analysis combining tradi-

tional pathologic and molecular results seems ideal. In low- risk

endometrioid carcinomas, the molecular classication may not be

required.

27 28

The proposed molecular classication of endometrial carcinoma

is clinically feasible using a limited set of diagnostic tests. Using

this novel classication is encouraged. All diagnostic tests should

be performed in conjunction due to the occurrence of 'double clas-

siers'.

23

Clinical management may be particularly impacted by the

molecular classication in scenarios where adjuvant chemotherapy

is considered (high- grade/high- risk disease). Thus, these cases

should be prioritized when there is a lack of sufcient resources to

perform this classication on all endometrial carcinomas. If molec-

ular classication tools are not available, endometrial carcinoma

classication should be based on traditional pathologic features.

There is still room for other biomarkers that may be potentially

useful in the big group of low- grade endometrioid carcinoma with

NSMP, such as L1CAM expression or mutations in CTNNB1.

29–32

Recommendations

► Molecular classication is encouraged in all endometrial carci-

nomas, especially high- grade tumors (IV, B).

► POLE mutation analysis may be omitted in low- risk and

intermediate- risk endometrial carcinoma with low- grade

histology (IV, C).

DEFINITION OF PROGNOSTIC RISK GROUPS INTEGRATING

MOLECULAR MARKERS

There is overwhelming evidence that traditional pathologic features,

such as histopathologic type, grade, myometrial invasion, and

lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI), are important in assessing

prognosis, as recommended in the ISGyP guidelines.

9

Histopatho-

logic typing should be performed according to the WHO Classica-

tion of Tumors (5th edition).

33

A binary International Federation of

Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) grading is recommended, which

considers grade 1 and grade 2 carcinomas as low- grade and grade

3 carcinomas as high- grade. For the assessment of myometrial

invasion, account needs to be taken of the endo- myometrial junc-

tion which is undulating.

34

Focal LVSI is dened by the presence

of a single focus around the tumor, substantial LVSI as multifocal

or diffuse arrangement of LVSI or the presence of tumor cells in

ve or more lymphovascular spaces. The molecular classication

adds another layer of information to the conventional morphologic

features and therefore should be integrated in the pathologic report.

Recommendations

► Histopathologic type, grade, myometrial invasion, and LVSI (no/

focal/substantial) should be recorded in all patients with endo-

metrial carcinoma (V, A).

► The denition of prognostic risk groups is presented in Table2

for both situations when molecular classication is known or

unknown.

PRE- AND INTRA-OPERATIVE WORK-UP

Risk group allocation on biopsy according to the WHO Classication

of Tumors (5th edition) and FIGO grading of endometrial carcinoma

is required for adequate planning of therapy.

33

Histopathologic

grade has prognostic relevance. A modied binary FIGO grading is

recommended lumping together grade 1 and grade 2 endometrioid

carcinomas as low- grade and grade 3 as high- grade.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques are highly specic

in the assessment of deep myometrial invasion, cervical stromal

involvement, and lymph node metastasis.

35–82

The diagnostic

performance of TVUS and MRI for detecting myometrial invasion

in endometrial carcinoma are quite similar.

39 44 56 83–88

Of note, pre-

operative ultrasound assessment of deep myometrial and cervical

stromal invasion in endometrial carcinoma is best performed by an

expert sonographer as, compared with gynecologists, they show

a greater degree of agreement with histopathology and greater

inter- observer reproducibility.

84

Positron emission tomography

(PET) scanning has an excellent specicity for the pre- operative

assessment of lymph node metastases in patients with endome-

trial carcinoma. Its moderate sensitivity for detecting lymph node

metastases during preo- perative staging probably reects the need

on August 30, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://ijgc.bmj.com/Int J Gynecol Cancer: first published as 10.1136/ijgc-2020-002230 on 18 December 2020. Downloaded from

16

ConcinN, etal. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2021;31:12–39. doi:10.1136/ijgc-2020-002230

Joint statement

for a sufcient number of neoplastic cells to induce

18

F- uoro-

2- deoxy- D- glucose hypermetabolism.

89–100

The usefulness of

maximal standardized uptake value in classifying patients into pre-

dened risk groups is limited.

101

A pre- operative CT scan has a

clinical utility in patients with endometrial carcinoma in detecting

metastatic disease.

102 103

Frozen section of endometrial biopsy material is obsolete.

Myometrial invasion should not be assessed by frozen section

because of poor reproducibility and agreement with denitive

parafn sections. Since sentinel node biopsy is increasingly used,

the need for intra- operative assessment of myometrial invasion has

become less important. Moreover, some of the biomarkers that have

been proposed require optimal management of the surgical spec-

imen with high quality pre- analytical issues such as appropriate

xation conditions. Performing frozen sections can lead to incor-

rect control of pre- analytical conditions, sometimes even leading

to incorrect assessment of LVSI due to artifactual displacement of

tumor cells into vascular spaces during processing. In addition, the

freezing of tissue before xation and further processing interferes

with an optimal pre- analytical procedure required for standardized

histopathologic diagnosis.

Recommendations

► Histopathologic tumor type and grade in endometrial biopsy is

required (IV, A).

► Pre- operative mandatory work- up includes: family history;

general assessment and inventory of co- morbidities; geriatric

assessment, if appropriate; clinical examination, including

pelvic examination; expert transvaginal or transrectal ultra-

sound or pelvic MRI (IV, C).

► Depending on clinical and pathologic risk, additional imaging

modalities (thoracic, abdominal and pelvic CT scan, MRI, PET

scan, or ultrasound) should be considered to assess ovarian,

nodal, peritoneal, and other sites of metastatic disease (IV, C).

Table 2 Denition of prognostic risk groups

Risk group Molecular classication unknown Molecular classication known*†

Low

► Stage IA endometrioid + low- grade‡ +

LVSI negative or focal

► Stage I–II POLEmut endometrial carcinoma,

no residual disease

► Stage IA MMRd/NSMP endometrioid

carcinoma + low- grade‡ + LVSI negative or focal

Intermediate

► Stage IB endometrioid + low- grade‡ +

LVSI negative or focal

► Stage IA endometrioid + high- grade‡ +

LVSI negative or focal

► Stage IA non- endometrioid (serous,

clear cell, undifferentiared carcinoma,

carcinosarcoma, mixed) without myometrial

invasion

► Stage IB MMRd/NSMP endometrioid

carcinoma + low- grade‡ + LVSI negative or focal

► Stage IA MMRd/NSMP endometrioid

carcinoma + high- grade‡ + LVSI negative or

focal

► Stage IA p53abn and/or non- endometrioid

(serous, clear cell, undifferentiated carcinoma,

carcinosarcoma, mixed) without myometrial

invasion

High–intermediate

► Stage I endometrioid + substantial LVSI

regardless of grade and depth of invasion

► Stage IB endometrioid high- grade‡

regardless of LVSI status

► Stage II

► Stage I MMRd/NSMP endometrioid

carcinoma + substantial LVSI regardless of grade

and depth of invasion

► Stage IB MMRd/NSMP endometrioid

carcinoma high- grade‡ regardless of LVSI status

► Stage II MMRd/NSMP endometrioid

carcinoma

High

► Stage III–IVA with no residual disease

► Stage I–IVA non- endometrioid (serous,

clear cell, undifferentiated carcinoma,

carcinosarcoma, mixed) with myometrial

invasion, and with no residual disease

► Stage III–IVA MMRd/NSMP endometrioid

carcinoma with no residual disease

► Stage I–IVA p53abn endometrial carcinoma

with myometrial invasion, with no residual

disease

► Stage I–IVA NSMP/MMRd serous,

undifferentiated carcinoma, carcinosarcoma with

myometrial invasion, with no residual disease

Advanced

metastatic

► Stage III–IVA with residual disease

► Stage IVB

► Stage III–IVA with residual disease of any

molecular type

► Stage IVB of any molecular type

*For stage III–IVA POLEmut endometrial carcinoma and stage I–IVA MMRd or NSMP clear cell carcinoma with myometrial invasion,

insufcient data are available to allocate these patients to a prognostic risk group in the molecular classication. Prospective registries are

recommended.

†See text on how to assign double classiers (eg, patients with both POLEmut and p53abn should be managed as POLEmut).

‡According to the binary FIGO grading, grade 1 and grade 2 carcinomas are considered as low- grade and grade 3 carcinomas are

considered as high- grade.

LVSI, lymphovascular space invasion; MMRd, mismatch repair decient; NSMP, non- specic molecular prole; p53abn, p53 abnormal;

POLEmut, polymerase- mutated.

on August 30, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://ijgc.bmj.com/Int J Gynecol Cancer: first published as 10.1136/ijgc-2020-002230 on 18 December 2020. Downloaded from

17

ConcinN, etal. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2021;31:12–39. doi:10.1136/ijgc-2020-002230

Joint statement

► Intra- operative frozen section is not encouraged for myometrial

invasion assessment because of poor reproducibility and inter-

ference with adequate pathologic processing (IV, A).

EARLY STAGE DISEASE

Surgical management of apparent stage I/II endometrial

carcinomas

Minimally invasive approach

Two randomized prospective studies comparing minimally invasive

with open surgeries showed similar survival with quicker recovery

with the minimally invasive approach.

104 105

More recently, pooled

analyses of randomized prospective studies including, notably, these

two studies and multiple retrospective and prospective studies also

support the use of minimally invasive surgery for patients including

those with high- risk endometrial carcinoma.

106–171

Recommendations

► Minimally invasive surgery is the preferred surgical approach,

including patients with high- risk endometrial carcinoma (I, A).

► Any intra- peritoneal tumor spillage, including tumor rupture or

morcellation (including in a bag), should be avoided (III, B).

► If vaginal extraction risks uterine rupture, other measures

should be taken (eg, mini- laparotomy, use of endobag) (III, B).

► Tumors with metastases outside the uterus and cervix

(excluding lymph node metastases) are relative contra-

indications for minimally invasive surgery (III, B).

Standard surgical procedures

In a randomized controlled trial comparing modied radical (Piver–

Rutledge class II) hysterectomy to the standard extrafascial (Piver–

Rutledge class I) or simple total hysterectomy in stage I endometrial

carcinoma, Signorelli et al showed no differences in locoregional

control and survival.

172

The high risk of microscopic omental metas-

tases in stage I serous and undifferentiated endometrial carcinoma

and in carcinosarcoma suggests that omentectomy should be part

of staging surgery in these patients.

173

The low rate of omental

metastases in apparent clinical stage I endometrioid and clear cell

carcinoma does not justify the procedure.

174

Although the risk of

having occult (microscopic) omental metastases in carcinosarcoma

is around 6%, staging omentectomy in these women is suggested.

Identication of these cases will allow inclusion of patients with

advanced stage disease into clinical trials.

175

Positive peritoneal

cytology correlates with poor prognostic factors and poor survival;

however, it is not part of FIGO staging and unclear if this should

inuence treatment decisions.

176–178

Recommendations

► Standard surgery is total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-

oophorectomy without vaginal cuff resection (II, A).

► Staging infracolic omentectomy should be performed in clinical

stage I serous endometrial carcinoma, carcinosarcoma, and

undifferentiated carcinoma. It can be omitted in clear cell and

endometrioid carcinoma in stage I disease (IV, B).

► Surgical re- staging can be considered in previously incom-

pletely staged patients with high– intermediate- risk/high- risk

disease if the outcome might have an implication for adjuvant

treatment strategy (IV, B).

Lymph node staging

Sentinel node biopsy has been introduced as an alternative to lymph

node dissection for lymph node staging and, if done according to

state- of- art principles, a negative sentinel node is accepted to

conrm pN0. Multiple studies, including prospective cohort ones,

conrmed high sensitivity of sentinel lymph node status for lymph

node staging in patients with early- stage endometrial carcinoma

and support the impact of sentinel lymph node biopsy on surgical

management and indications for adjuvant therapies.

179–241

More

intensive pathologic assessment of sentinel lymph node (sentinel

lymph node ultrastaging) supports the detection of small metas-

tases which could be missed by standard evaluation.

214 232

Sentinel

lymph node biopsy without dissection of other pelvic lymph nodes is

associated with subtantially lower risk of post- operative morbidity,

especially lower leg lymphedema.

242

In a large group of patients

with low- risk (myometrial invasion <50%, low- grade) endometrial

carcinoma with sentinel lymph node biopsy, lymph node involve-

ment was found in 6% of patients, half of them identied by patho-

logic ultrastaging.

243

Patients with tumors without myometrial inva-

sion did not have any positive sentinel lymph nodes. Four prospec-

tive cohort trials have shown high sensitivity to detect pelvic lymph

node metastases and a high negative predictive value by applying

a sentinel lymph node algorithm in high- risk/high- grade endome-

trial carcinomas in the hands of experienced surgeons.

181 182 237 244

Recently, a randomized controlled trial highlighted that the use

of indocyanine green instead of methylene blue dye resulted in

a signicant increase in sentinel lymph node detection rates per

hemipelvis in women with endometrial carcinoma undergoing mini-

mally invasive surgery.

245

Retrospective studies showed a similar

prognosis for patients after full lymphadenectomy and sentinel

lymph node biopsy only.

179 201 220

High bilateral pelvic sentinel

lymph node detection can be achieved when the tracer is injected

into the cervix.

180 246

A higher sentinel lymph node detection rate

has been reported using near- infrared uorescence in comparison

to other techniques.

247

A worse prognosis is associated with the

presence of nodal micrometastases, especially in patients who do

not receive adjuvant treatment.

248

There is no evidence that the

presence of isolated tumor cells (ITCs) has an impact on prognosis,

and similar to other tumor sites, the stage would be pN0(i+). If

pelvic lymph node involvement is reported either by sentinel lymph

node frozen section or by the nal pathology, para- aortic staging

can be considered, either by imaging (with all limitations of the

imaging modalities) or by surgery. It should be noted that, based on

data from two large randomized trials, lymph node staging does not

have a therapeutic value but is done to assess the extent of disease

and to provide information for adjuvant treatment decisions.

249 250

Frozen section on specimens regarded as sentinel lymph nodes

can conrm the presence of lymph nodes and macrometastases

but should not replace adequate pathologic processing and ultrast-

aging.

Recommendations

► Sentinel lymph node biopsy can be considered for staging

purposes in patients with low- risk/intermediate- risk disease. It

can be omitted in cases without myometrial invasion. System-

atic lymphadenectomy is not recommended in this group (II, A).

► Surgical lymph node staging should be performed in patients

with high–intermediate- risk/high- risk disease. Sentinel

on August 30, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://ijgc.bmj.com/Int J Gynecol Cancer: first published as 10.1136/ijgc-2020-002230 on 18 December 2020. Downloaded from

18

ConcinN, etal. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2021;31:12–39. doi:10.1136/ijgc-2020-002230

Joint statement

lymph node biopsy is an acceptable alternative to systematic

lymphadenectomy for lymph node staging in stage I/II (III, B).

► If sentinel lymph node biopsy is performed (II, A):

– Indocyanine green with cervical injection is the preferred

detection technique.

– Tracer re- injection is an option if sentinel lymph node is not

visualized upfront.

– Side- specic systematic lymphadenectomy should be per-

formed in high–intermediate- risk/high- risk patients if senti-

nel lymph node is not detected on either pelvic side.

– Pathologic ultrastaging of sentinel lymph nodes is

recommended.

► When a systematic lymphadenectomy is performed, pelvic and

para- aortic infrarenal lymph node dissection is suggested (III,

B).

► Presence of both macrometastases and micrometastases

(<2 mm, pN1(mi)) is regarded as a metastatic involvement (IV,

C).

► The prognostic signicance of ITCs, pN0(i+), is still uncertain

(IV, C).

► If pelvic lymph node involvement is found intra- operatively,

further systematic pelvic lymph node dissection should be

omitted. However, debulking of enlarged lymph nodes and

para- aortic staging can be considered (IV, B).

Option for ovarian preservation and salpingectomy in stage I/II

A meta- analysis showed that there was no signicant difference

in overall survival between patients treated with ovarian preser-

vation and bilateral salpingo- oophorectomy.

251

A similar result

was achieved in young and pre- menopausal women. Disease- free

survival of patients whose ovaries were preserved was slightly

compromised, but this was not statistically signicant. Ovarian

preservation can be cautiously considered in specic clinical situa-

tions when treating young and pre- menopausal women with early

stage endometrial carcinoma because it is not associated with a

signicant adverse impact on survival.

252–254

Salpingectomy during

hysterectomy is recommended to decrease the risk of high- grade

serous ovarian carcinoma.

255

Ovarian preservation is not recom-

mended in patients with cancer family history involving ovarian

cancer risk (eg, BRCA mutation, Lynch syndrome, etc), but oocyte

cryopreservation might be considered.

256

Recommendations

► Ovarian preservation can be considered in pre- menopausal

patients aged <45 years with low- grade endometrioid endo-

metrial carcinoma with myometrial invasion <50% and no

obvious ovarian or other extra- uterine disease (IV, A).

► In cases of ovarian preservation, salpingectomy is recom-

mended (IV, B).

► Ovarian preservation is not recommended for patients with

cancer family history involving ovarian cancer risk (eg, BRCA

mutation, Lynch syndrome, etc) (IV, B).

Radicality of surgery for clinical stage II

Radicality of hysterectomy (simple vs modied radical hysterec-

tomy (type II)) in stage I–III endometrial carcinoma has no impact

on local recurrence rate, disease- free survival, and overall survival.

In a meta- analysis enrolling 2866 patients with stage II endometrial

carcinoma, radical hysterectomy did not show a signicant survival

benet for either overall survival or progression- free survival

compared with simple hysterectomy.

257

The result remained

consistent after it was adjusted for the possible impact of adjuvant

radiotherapy.

Recommendations

► Total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo- oophorectomy and

lymph node staging is the surgical standard of care in patients

with stage II endometrial carcinoma (IV, B).

► More extensive procedures should only be performed if required

to achieve free surgical margins (IV, B).

Medically unt patients

It is rare for patients to be unt for surgery, but medical co- morbidi-

ties, which increasingly include morbid obesity, can preclude surgery

due to high operative and peri- operative risks. Ideally, assessment

should be undertaken in a center with specialist anesthetic experi-

ence in managing these high- risk patients. Denitive radiotherapy

with brachytherapy, external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) or the

combination of both modalities can be considered.

258–262

Recommendations

► Medical contra- indications to the standard surgical manage-

ment by minimally invasive surgery are rare. Vaginal hyster-

ectomy, with bilateral salpingo- oophorectomy if feasible, can

be considered in patients unt for the recommended standard

surgical therapy (IV, C).

► Denitive radiotherapy can be considered for primary tumors

where surgery is contra- indicated for medical reasons:

– The combination of EBRT and brachytherapy should be used

for high- grade tumors and/or deep myometrial invasion (II,

B).

– For low- grade tumors, brachytherapy alone can be consid-

ered (II, B).

– In medically unt patients unsuitable for curative surgery or

radiotherapy, systemic treatment (including hormonal ther-

apy) can be considered (IV, B).

Fertility preservation

Work-up for fertility preservation treatments

Fertility- sparing treatments should be considered in patients with

atypical hyperplasia/endometrioid intra- epithelial neoplasia (AH/

EIN) or grade 1 endometrioid carcinoma without myometrial inva-

sion.

263–269

There are very few published data on patients with

stage IA grade 2 endometrioid carcinoma without myometrial

invasion who received fertility- sparing treatment with combined

oral medroxyprogesterone acetate/levonorgestrel intrauterine

system.

270

Although results are encouraging, this treatment should

only be considered by experienced gynecological oncologists using

well- dened protocols with detailed patient information and close

follow- up.

Hysteroscopic biopsy is suggested, based on its higher agree-

ment with the nal diagnosis compared with dilatation and curet-

tage.

271 272

Although hysteroscopy seems to be associated with a

higher rate of positive peritoneal cytology, it seems not to have a

negative impact on survival.

273

Expert vaginal ultrasound examina-

tion can be used instead of pelvic MRI. Its high diagnostic perfor-

mance allows the detection of myometrial invasion and cervical

on August 30, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://ijgc.bmj.com/Int J Gynecol Cancer: first published as 10.1136/ijgc-2020-002230 on 18 December 2020. Downloaded from

19

ConcinN, etal. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2021;31:12–39. doi:10.1136/ijgc-2020-002230

Joint statement

stromal invasion with respect to nal pathologic examination.

Ultrasound should be performed by an expert sonographer (a prac-

titioner who spends a signicant part of her/his time undertaking

ultrasound examinations in gynecology and gynecologic oncology

and has fullled the minimum training requirements for level 3

following the recommendations of the European Federation of Soci-

eties for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology).

274

There is currently a lack of high- quality evidence regarding the

correlation between weight loss and reduction of risk of recurrence/

increased survival in patients with endometrial carcinoma, espe-

cially with respect to fertility- sparing treatment.

275

Diabetes mellitus

does not seem to affect the outcome of conservative treatment in

women with AH/EIN or early endometrial carcinoma.

276

Conversely,

the use of metformin seems associated with an improvement in

overall survival for patients with endometrial carcinoma and a

reduced risk of cancer relapse.

277

In addition, metformin is associ-

ated with improvement in the overall survival of patients with endo-

metrial carcinoma with diabetes.

Recommendations

► Patients who are candidates for fertility- preserving treatment

must be referred to specialized centers. Fertility- sparing treat-

ment should be considered only in patients with AH/EIN or

grade 1 endometrioid endometrial carcinoma without myome-

trial invasion and without genetic risk factors (V, A).

► In these patients, endometrial biopsy, preferably through

hysteroscopy, must be performed (III, A).

► AH/EIN or grade 1 endometrioid endometrial carcinoma must

be conrmed/diagnosed by a pathologist experienced in gyne-

cological pathology (V, A).

► Radiologic imaging to assess the extension of the disease must

be performed. An expert ultrasound examination can substitute

pelvic MRI scan (III, B).

► Patients must be informed that fertility- sparing treatment is

not a standard treatment. Only patients who strongly desire

to preserve fertility should be treated conservatively. Patients

must be willing to accept close follow- up and be informed of

the need for future hysterectomy in case of failure of treatment

and/or after pregnancies (V, A).

Management and follow-up for fertility preservation

To date, there are no available randomized controlled trials

comparing different methods of conservative treatment in women

with AH/EIN or presumed stage IA grade 1 endometrioid carci-

noma. Existing data suggest that patients who received hystero-

scopic resection followed by progestin therapy achieve the highest

complete remission rate compared with other existing fertility-

preserving treatments.

263–269 278–295

Intrauterine progestin therapy

such as levonorgestrel- releasing intrauterine system combined with

gonadotropin- release hormone receptor agonist/progestin have a

satisfactory pregnancy rate and low recurrence rate. Patients who

received oral progestin only might be more likely to recur and have

more systemic adverse effects.

Recommendations

► All patients should be evaluated before and after the fertility-

sparing treatment at a fertility clinic (IV, C).

► Hysteroscopic resection prior to progestin therapy can be

considered (III, B).

► Medroxyprogesterone acetate (400–600 mg/day) or megestrol

acetate (160–320 mg/day) is the recommended treatment.

Treatment with levonorgestrel intrauterine device in combina-

tion with oral progestins with or without gonadotropin- releasing

hormone analogs can also be considered (IV, B).

► In order to assess response, hysteroscopic guided biopsy

and imaging at 3–4 and 6 months must be performed. If no

response is achieved after 6 months, standard surgical treat-

ment is recommended (IV, B).

► Continuous hormonal treatment should be considered in

responders who wish to delay pregnancy (IV, B).

► Strict surveillance is recommended every 6 months with TVUS

and physical examination. During follow- up, hysteroscopic

and endometrial biopsy should be performed only in case of

abnormal uterine bleeding or atypical ultrasound ndings (IV,

B).

► Fertility- sparing treatment can be considered for intrauterine

recurrences only in highly selected cases under strict surveil-

lance (IV, C).

► Hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo- oophorectomy is recom-

mended after childbearing due to a high recurrence rate. Pres-

ervation of the ovaries can be considered depending on age

and genetic risk factors (IV, B).

Synchronous presentation of low-grade endometrioid

endometrial and ovarian carcinomas

Adnexal involvement by endometrial carcinoma is currently a

parameter important in FIGO staging and has an impact on overall

survival rate.

296

It was shown that patients with simultaneous

involvement of the endometrium and ovary by low- grade endo-

metrioid carcinoma had a favorable outcome. This suggested that

they were synchronous primary tumors rather than metastatic

sites. Several criteria have been used in the past to distinguish

between endometrial carcinoma with ovarian metastasis and

synchronous primary tumors.

297 298

However, these were not easy

to apply.

Recent studies have shown that, for low- grade endometrioid

carcinomas, there is a clonal relationship between endometrial and

ovarian carcinomas in the vast majority of cases, indicating that

the carcinoma arises in the endometrium and extends secondarily

to the ovary.

299 300

In the most recent edition of WHO (2020) it is

mentioned that patients with clonally related low- grade endome-

trioid carcinomas should be managed without adjuvant treatment

(as if they were two independent primaries) when fullling the

following criteria: (1) low- grade endometrioid morphology, (2) no

more than supercial myometrial invasion, (3) absence of LVSI, and

(4) absence of additional metastases.

33 301

Recommendation

► If all WHO 2020 criteria mentioned above are met and the

ovarian carcinoma is pT1a, no adjuvant treatment is recom-

mended (III, B).

ADJUVANT TREATMENT

Adjuvant treatment recommendations for endometrial carcinoma

strongly depend on the prognostic risk group (see Table 2 for

on August 30, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://ijgc.bmj.com/Int J Gynecol Cancer: first published as 10.1136/ijgc-2020-002230 on 18 December 2020. Downloaded from

20

ConcinN, etal. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2021;31:12–39. doi:10.1136/ijgc-2020-002230

Joint statement

denitions of the prognostic risk groups with and without known

molecular classication).

Low risk

For patients with low- risk endometrial carcinoma, no adjuvant treat-

ment is recommended based on data from multiple randomized

trials.

302–305

For patients with stage I–II POLEmut endometrial carci-

nomas, no adjuvant treatment seems justiable based on the data

from independent series showing very few recurrences and also

in cases of observation.

21 25

For stage III patients, however, there

are only indirect data to support this, as all cases with advanced

disease had adjuvant treatment. In the molecular analysis of the

PORTEC-3 trial of high- risk endometrial carcinoma, those with

POLEmut endometrioid carcinoma had an excellent outcome in both

arms.

22

However, both trial arms included EBRT. Prospective regis-

tration (preferably in national or international studies) of POLEmut

endometrial carcinoma cases with treatment and outcome data is

strongly recommended.

Recommendations

► For patients with low- risk endometrial carcinoma, no adjuvant

treatment is recommended (I, A).

► When molecular classication is known:

– For patients with endometrial carcinoma stage I–II, low- risk

based on pathogenic POLE- mutation, omission of adjuvant

treatment should be considered (III, A).

– For the rare patients with endometrial carcinoma stage

III–IVA and pathogenic POLE-mutation, there are no out-

come data with the omission of the adjuvant treatment.

Prospective registration is recommended (IV, C).

Intermediate risk

Adjuvant brachytherapy provides excellent vaginal control and

high survival rates, similar to those after adjuvant EBRT in this

intermediate- risk population, as shown in large randomized trials,

particularly the PORTEC-2 trial and Swedish trial.

306–314

It was also

shown that only the small minority of patients with higher risk

based on substantial LVSI, p53abn, or L1CAM overexpression had a

slightly higher risk of pelvic recurrence with vaginal brachytherapy

than those who had EBRT. Therefore, the intermediate- risk category

only includes those with none or only focal LVSI and no p53abn. In

a Danish population study it was conrmed that the risk of locore-

gional relapse was higher (about 14%) with omission of vaginal

brachytherapy, but that overall survival was not different due to

treatment of relapse.

315

Therefore, no adjuvant treatment is an

option in this group, especially for patients aged <60 years who

have a lower risk of relapse.

MMRd and, especially, NSMP cancers form the majority of

endometrioid carcinomas and have an intermediate prognosis, in

between POLEmut (excellent prognosis) and p53abn carcinomas

(unfavorable prognosis). Findings of prior large randomized trials

in high–intermediate- risk endometrial carcinoma are therefore

mainly applicable to MMRd and NSMP endometrioid carcinomas in

this intermediate- risk category.

It has to be stressed that p53abn carcinomas restricted to

a polyp or without myometrial invasion were not included in the

randomized trials and the value of chemotherapy and of EBRT are

uncertain. Since the studies mentioned above did not include and/

or did not address non- endometrioid (and/or p53abn) carcinomas

without myometrial invasion, there are very few specic available

data on the best treatment for stage IA non- endometrioid carci-

nomas (serous, clear cell, undifferentiated carcinoma, carcinosar-

coma, mixed) without myometrial invasion. Some case series and

a recent analysis using the US National Cancer Data Base suggest

that adjuvant chemotherapy (with or without vaginal brachytherapy)

might improve survival, while other reports showed good outcomes

with vaginal brachytherapy only.

306

Therefore, these carcinomas

have been grouped in the intermediate- risk category and adjuvant

therapy should be discussed on a case- by- case basis until more

prospective data are available.

Recommendations

► Adjuvant brachytherapy can be recommended to decrease

vaginal recurrence (I, A).

► Omission of adjuvant brachytherapy can be considered (III, C),

especially for patients aged <60 years (II, A).

► When molecular classication is known, POLEmut and p53abn

with myometrial invasion have specic recommendations (see

respective recommendations for low- and high- risk).

► For p53abn carcinomas restricted to a polyp or without myome-

trial invasion, adjuvant therapy is generally not recommended

(III, C).

High–intermediate risk (pN0 after lymph node staging)

The denition of high–intermediate risk has changed in compar-

ison with the ESMO- ESGO- ESTRO consensus conference. In the

current prognostic risk group classication (see Table2), stage IA

endometrioid carcinomas are only included if there is substantial

LVSI.

3–5

This high–intermediate- risk group also includes stage IB

low- grade endometrioid with substantial LVSI, and stage IB high-

grade endometrioid carcinomas regardless of LVSI, and stage II

endometrioid carcinomas. In view of the higher risk of recurrence

in this newly classied group (even with negative nodes), adjuvant

brachytherapy can be recommended to decrease vaginal recur-

rence. In the case of substantial LVSI and/or stage II, EBRT can be

considered as it has been shown to reduce the risk of pelvic and

para- aortic nodal relapse.

316

In two older randomized controlled trials

317 318

there was no

difference between adjuvant chemotherapy alone and EBRT

alone in recurrence- free and overall survival. In the NSGO/EORTC

trial and the PORTEC-3 trials, the combination of chemotherapy

and radiotherapy seemed to provide better recurrence- free and

overall survival outcomes respectively compared with radiotherapy

alone.

319 320

The GOG-249 trial did not nd benet in recurrence-

free or overall survival from three cycles of chemotherapy with

brachytherapy compared with EBRT alone.

316

Molecular analysis

of PORTEC-3 trial tissues suggested no benet of chemotherapy

for MMRd carcinomas.

320 321

Omission of adjuvant treatment is an

option and this should be considered only when close follow- up

is guaranteed to ensure detection and prompt treatment of recur-

rence at an early stage.

Recommendations

► Adjuvant brachytherapy can be recommended to decrease

vaginal recurrence (II, B).

on August 30, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://ijgc.bmj.com/Int J Gynecol Cancer: first published as 10.1136/ijgc-2020-002230 on 18 December 2020. Downloaded from

21

ConcinN, etal. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2021;31:12–39. doi:10.1136/ijgc-2020-002230

Joint statement

► EBRT can be considered for substantial LVSI and for stage II

(I, B).

► Adjuvant chemotherapy can be considered, especially for high-

grade and/or substantial LVSI (II, C).

► Omission of any adjuvant treatment is an option (IV, C).

► When molecular classication is known, POLEmut and p53abn

have specic recommendations (see respective recommenda-

tions for low- and high- risk).

High–intermediate risk cN0/pNx (lymph node staging not

performed)

In view of the recent randomized trials GOG-249 (for stage I and II

endometrial carcinomas with high- risk factors or serous or clear

cell histology), the PORTEC-3 trial and the older GOG-99 trial, adju-

vant EBRT is recommended in case of substantial LVSI or stage

II.

302 316 319 320 322

Additional chemotherapy can be considered, espe-

cially for high- grade carcinomas, based on the PORTEC-3 trial, but

the question remains whether the benet outweighs the toxicity for

stage I–II endometrioid carcinomas, and multi- disciplinary shared

decision- making is needed.

320

Molecular analysis of PORTEC-3 trial

tissues suggested no benet of chemotherapy for MMRd carci-

nomas.

320 321

Adjuvant brachytherapy alone can be considered for

LVSI negative cases and for stage II grade 1 disease.

Recommendations

► Adjuvant EBRT is recommended, especially for substantial LVSI

and/or for stage II (I, A).

► Additional adjuvant chemotherapy can be considered, espe-

cially for high- grade and/or substantial LVSI (II, B).

► Adjuvant brachytherapy alone can be considered for high- grade

LVSI negative and for stage II grade 1 endometrioid carcinomas

(II, B).

► When molecular classication is known, POLEmut and p53abn

have specic recommendations (see respective recommenda-

tions for low- and high- risk).

High risk

The risk category changes also have a substantial impact on this

category. Some carcinomas designated as high risk in the ESMO-

ESGO- ESTRO consensus conference are not included anymore in

the high- risk sub- group in these ESGO- ESTRO- ESP guidelines.

3–5

High- risk carcinomas are now either stage III–IVA without residual

disease or stage I–IVA p53abn or non- endometrioid carcinomas

without residual disease with myometrial invasion (for specics see

Table2).

In 2019 the updated results of the PORTEC-3 trial, with a longer

median follow- up of 72 months and with 75% of participants

having reached 5 years of follow- up, were published.

323

In this

trial comparing combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy (two

cycles of cisplatin during radiotherapy followed by four cycles

of carboplatin- paclitaxel) with radiotherapy alone, a statistically

signicant 5% overall survival benet at 5 years and a 7% failure-

free survival benet was seen in the combined therapy group

compared with radiotherapy alone. The greatest overall survival

difference was seen in stage III carcinomas and in serous carci-

nomas regardless of stage. The GOG-258 trial compared the same

chemotherapy- radiotherapy schedule used in PORTEC-3 with six

cycles of carboplatin- paclitaxel chemotherapy alone and found

overlapping relapse- free and overall survival rates.

324

However, the

chemotherapy alone arm had signicantly higher rates of pelvic

and peri- aortic nodal relapse. Therefore, chemotherapy alone is

an alternative option based on the GOG-258 results for stage III–

IV disease. The nal analysis of the GOG-249 trial highlighted that

a post- operative adjuvant strategy of vaginal cuff brachytherapy

followed by three cycles of paclitaxel and carboplatin chemotherapy

did not signicantly increase 5- year recurrence- free survival or

5- year overall survival compared with pelvic radiotherapy.

325

Vaginal and distant recurrence rates were similar between arms.

However, pelvic or para- aortic nodal recurrences were signicantly

less common with pelvic radiotherapy. The older pooled analysis

of the NSGO- EORTC and MANGO- ILIADE trials used sequential

chemotherapy and radiotherapy (either sequence) and reported

signicantly longer recurrence- free survival compared with radio-

therapy alone.

319

Multiple retrospective studies indicated a survival

benet in patients with advanced stage endometrial carcinoma

treated with post- operative combined treatment including radio-

therapy and chemotherapy, delivered by either the sandwich or

sequential method, compared with radiotherapy alone or chemo-

therapy alone.

326–344

The benet of added chemotherapy is unclear for patients with

stage I–II clear cell carcinomas. These have often been included

with serous as 'non- endometrioid carcinomas'. Of note, in the

PORTEC-3 trial it was specically in those with serous histology

that a signicant benet of added chemotherapy was seen.

323

However, this was not observed in the NSGO- EORTC and MANGO-

ILEADE trials. Extended eld radiotherapy is used in the case of

involved para- aortic nodes or involvement of high common iliac

nodes, both with or without chemotherapy. The combination of

extended eld radiotherapy with chemotherapy using modern

intensity- modulated radiation therapy/volumetric modulated arc

therapy (IMRT/VMAT) techniques has been shown feasible in the

PORTEC-3 and GOG-258 trials. An additional brachytherapy boost

can be considered, especially for substantial LVSI, endocervical

stromal invasion, and/or stage IIIB–IIIC.

MMRd and NSMP carcinomas are included in the high- risk cate-

gory if stage III–IVA with no residual disease. The p53abn carci-

nomas can be of endometrioid, serous, undifferentiated, and clear

cell histologic type, but all consistently show a poor outcome and

should therefore be regarded as high risk. Based on the current

data, it is more difcult to draw conclusions regarding carcino-

sarcomas and undifferentiated carcinomas that are NSMP endo-

metrial carcinomas due to the lack of large series. For clear cell

carcinomas, the available data suggest some prognostic infor-

mation may lie in the molecular classication. About 40–50% of

clear cell carcinomas are p53abn. While serous carcinomas in the

PORTEC-3 trial had an unfavorable outcome and signicant benet

of added adjuvant chemotherapy, those with clear cell carcinomas

seemed to have an outcome similar to high- grade carcinomas in

general and were more favorable if not p53abn.

321 323

The ndings

of the randomized trials for endometrioid carcinomas cited above

are therefore largely applicable to stage III MMRd and NSMP carci-

nomas and to stage I–III p53abn carcinomas. This was also seen

in the molecular analysis of the PORTEC-3 trial, which showed a

statistically signicant survival advantage for p53abn carcinomas

with combined therapy for stage I–III. In contrast, POLEmut carci-

nomas had almost no recurrences in both arms. There was no clear

on August 30, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://ijgc.bmj.com/Int J Gynecol Cancer: first published as 10.1136/ijgc-2020-002230 on 18 December 2020. Downloaded from

22

ConcinN, etal. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2021;31:12–39. doi:10.1136/ijgc-2020-002230

Joint statement

benet of added chemotherapy for MMRd, while the NSMP carci-

nomas had some benet of added chemotherapy especially in case

of stage III. Prospective evaluation of the molecular characteristics

in randomized trials is highly recommended.

Recommendations

► EBRT with concurrent and adjuvant chemotherapy (I, A) or

alternatively sequential chemotherapy and radiotherapy is

recommended (I, B).

► Chemotherapy alone is an alternative option (I, B).

► Carcinosarcomas should be treated as high- risk carcinomas

(not as sarcomas) (IV, B).

► When the molecular classication is known, p53abn carci-

nomas without myometrial invasion and POLEmut have specic

recommendations (see respective recommendations for low-

and intermediate- risk) (III, C).

ADVANCED DISEASE

Surgery for clinically overt stage III and IV disease

In stage III and IV endometrial carcinoma (including carcinosarcoma),

maximal cytoreduction should be considered only if macroscopic

complete resection is feasible with acceptable morbidity.

345–350

Surgery should be performed in a specialized center. Pre- operative

complete staging and multi- disciplinary discussion within a tumor

board should be performed. Suspicious enlarged lymph nodes

should be resected if complete resection is possible.

351 352

A full

systematic pelvic and para- aortic lymphadenectomy of non-

suspicious lymph nodes should not be performed because there

is no evidence of a therapeutic impact. If upfront surgery is not

feasible or acceptable and therefore primary systemic therapy is

given, delayed surgery can be considered in case of a meaningful

response to chemotherapy.

353–360

Recommendations

► In stage III and IV endometrial carcinoma (including carcino-

sarcoma), surgical tumor debulking including enlarged lymph

nodes should be considered when complete macroscopic

resection is feasible with an acceptable morbidity and quality of

life prole, following full pre- operative staging and discussion

by a multi- disciplinary team (IV, B).

► Primary systemic therapy should be used if upfront surgery is

not feasible or acceptable (IV, A).

► In cases of a good response to systemic therapy, delayed

surgery can be considered (IV, C).

► Only enlarged lymph nodes should be resected. Systematic

lymphadenectomy is not recommended (IV, B).

Unresectable primary tumor due to local extent of disease

For patients presenting with unresectable locally advanced disease

and no evidence of multiple distant metastases, treatment options

include denitive radiotherapy or neoadjuvant chemotherapy

followed by surgery or denitive radiotherapy, depending on

response.

261 354–356 361

Denitive radiotherapy comprises EBRT to

the pelvis followed by image- guided brachytherapy. Concurrent

chemotherapy may be considered to enhance the radiation effect.

Brachytherapy should boost sites of macroscopic disease in the

uterus, parametrium, or vagina using the ESTRO principles. Adju-

vant chemotherapy should also be considered following primary

local treatment (surgery or radiotherapy) to reduce the risk of

distant metastases.

Recommendations

► For unresectable tumors, multi- disciplinary team discussion

should consider denitive radiotherapy with EBRT and intra-

uterine brachytherapy, or neoadjuvant chemotherapy prior

to surgical resection or denitive radiotherapy, depending on

response (IV, C).

► Image- guided brachytherapy is recommended to boost intrau-

terine, parametrial, or vaginal disease (IV, A).

► Chemotherapy should be considered after denitive radio-

therapy (IV, B).

Residual pelvic or para-aortic lymph nodes following surgery

Residual lymph node disease can be treated with EBRT using an

integrated or sequential boost to escalate the nodal dose. An IMRT

technique reduces the risk of toxicity to surrounding tissue.

362

Adjuvant chemotherapy reduces the risk of distant metastases for

patients with lymph node involvement.

320 323 324

Recommendations

► Residual lymph node disease should be treated with a combi-

nation of chemotherapy and EBRT (III, B) or chemotherapy

alone (IV, B).

► EBRT should be delivered to pelvis and para- aortic nodes

with dose escalation to involved nodes using an integrated or

sequential boost (IV, B).

Residual pelvic disease (positive resection margin, vaginal

disease, pelvic side wall disease)

Patients with residual pelvic disease following surgery have a high

risk of both local and distant recurrence. Radiotherapy can achieve

long- term local control while chemotherapy reduces the risk of

distant metastases. An individualized approach with either (chemo)-

radiotherapy to the pelvis followed by chemotherapy or adjuvant

chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy to the pelvis±para- aortic

nodes should be considered.

Recommendation

► An individualized approach with either radiotherapy or chemo-

therapy or a combination of both modalities should be consid-

ered by a multi- disciplinary team (V, B).

RECURRENT DISEASE

Radiotherapy naïve patients

Treatment of patients with recurrent endometrial carcinoma

involves a multi- disciplinary approach with surgery, radiotherapy,

and/or systemic therapy depending on the tness and wishes of

the patient, the tumor dissemination patterns, and prior treatment.

A decision about surgery needs to take account of patient morbidity

and wishes, available non- surgical treatments, and resources. The

interval between primary treatment and recurrence should also be

taken into consideration. Patients with recurrent disease, including

resectable peritoneal and lymph node relapse, should be consid-

ered for surgery only if it is anticipated that complete resection of

macroscopic disease can be achieved with a reasonable morbidity

prole.

363–369

The extent of the operation will depend on the degree

of tumor dissemination pattern.

on August 30, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://ijgc.bmj.com/Int J Gynecol Cancer: first published as 10.1136/ijgc-2020-002230 on 18 December 2020. Downloaded from

23

ConcinN, etal. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2021;31:12–39. doi:10.1136/ijgc-2020-002230

Joint statement

Locoregional recurrence of endometrial carcinoma is rare. With

the advent of modern image- guided radiation therapy, including

IMRT and image- guided adaptive brachytherapy, radiotherapy

has become the treatment of choice in previously non- irradiated

patients with isolated vaginal recurrence or locoregional recur-

rence.

363 364 370–379

Consideration should be given to remove solitary

easily accessible vaginal relapses, for better local symptom control

prior to radiotherapy.

Recommendations

► Patients with recurrent disease (including peritoneal and lymph

node relapse) should be considered for surgery only if it is

anticipated that complete removal of macroscopic disease can

be achieved with acceptable morbidity. Systemic and/or radia-

tion therapy should be considered post- operatively depending

on the extent and pattern of relapse and the amount of residual

disease (IV, C).

► In selected cases, palliative surgery can be performed to alle-

viate symptoms (eg, bleeding, stula, bowel obstruction) (IV, B).

► For locoregional recurrence, the preferred primary therapy

should be EBRT±chemotherapy with brachytherapy (IV, A).

► An easily accessable supercial vaginal tumor can be resected

vaginally prior to radiotherapy (IV, C).

► For vaginal cuff recurrence:

– Pelvic EBRT+intracavitary (±interstitial) image- guided

brachytherapy is recommended (IV, A).

– In case of supercial tumors, intracavitary brachytherapy

alone can be considered (IV, A).

► Systemic treatment can be considered before or after radio-

therapy (IV, C).

Radiotherapy pre-treated patients with locoregional

recurrence

In patients who have previously received EBRT±brachytherapy,

radical surgery with the intention of complete resection with clear

margins should be considered in specialized centers after ruling out

metastatic disease with modern imaging. Pelvic exenteration may

be considered for central local relapse.

349 380 381

Otherwise, further

radiation should be considered as radical therapy with or without

systemic therapy. Interstitial brachytherapy (low- dose rate or high-

dose rate) as the sole modality of treatment or combined with EBRT

can result in high local control over 1–5 years.

374

375 382 383

Other

techniques like permanent seed implant or post- operative elec-

tron irradiation, protons and stereotactic body radiotherapy may be

recommended in highly selected patients.

384–386

The appropriate

dose for each case needs to be individualized. Some low- dose rate

data suggest improved outcomes with doses >50 Gy. The high- dose

rate data are more varied, suggesting improved local control with

doses >40 Gy. In general, a longer time interval between the rst

and second course of radiation as well as recurrences <2–4 cm

tend to have improved outcomes. Multi- disciplinary management is

critical to develop individualized plans and to clearly communicate