1455

KurnitKC, FrumovitzM. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2022;32:1455–1462. doi:10.1136/ijgc-2022-003806

Primary mucinous ovarian cancer: options for

surgery andchemotherapy

Katherine C Kurnit ,

1

Michael Frumovitz

2

1

Department of Obstetrics

and Gynecology, University of

Chicago Medicine, Chicago,

Illinois, USA

2

Department of Gynecologic

Oncology and Reproductive

Medicine, University of Texas

MD Anderson Cancer Center,

Houston, Texas, USA

Correspondence to

Dr Katherine C Kurnit,

Department of Obstetrics

and Gynecology, University of

Chicago Biological Sciences

Division, Chicago, IL 60637,

USA; kkurnit@ uchicago. edu

Received 11 July 2022

Accepted 27 September 2022

Published Online First

13October2022

To cite: KurnitKC,

FrumovitzM. Int J Gynecol

Cancer 2022;32:1455–1462.

Review

© IGCS and ESGO 2022. No

commercial re- use. See rights

and permissions. Published by

BMJ.

Original research

Editorials

Joint statement

Society statement

Meeting summary

Review articles

Consensus statement

Clinical trial

Tumor board

Video articles

Educational video lecture

Images

Pathology archives

Corners of the world

Commentary

Letters

ijgc.bmj.com

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF

GYNECOLOGICAL CANCER

ABSTRACT

Primary mucinous ovarian cancer is a rare type of

epithelial ovarian cancer. In this comprehensive review we

discuss management recommendations for the treatment

of mucinous ovarian cancer. Although most tumors are

stage I at diagnosis, 15–20% are advanced stage at

diagnosis. Traditionally, patients with primary mucinous

ovarian cancer have been treated similarly to those with

the more common serous ovarian cancer. However, recent

studies have shown that mucinous ovarian cancer is very

different from other types of epithelial ovarian cancer.

Primary mucinous ovarian cancer is less likely to spread

to lymph nodes or the upper abdomen and more likely to

affect younger women, who may desire fertility- sparing

therapies. Surgical management of mucinous ovarian

cancer mirrors surgical management of other types of

epithelial ovarian cancer and includes a bilateral salpingo-

oophorectomy and total hysterectomy. When staging is

indicated, it should include pelvic washing, omentectomy,

and peritoneal biopsies; lymph node evaluation should

be considered in patients with inltrative tumors. The

appendix should be routinely evaluated intra- operatively,

but an appendectomy may be omitted if the appendix

appears grossly normal. Fertility preservation can be

considered in patients with gross disease conned to one

ovary and a normal- appearing contralateral ovary. Patients

with recurrent platinum- sensitive disease whose disease

distribution suggests a high likelihood of complete gross

resection may be candidates for secondary debulking.

Primary mucinous ovarian cancer seems to be resistant to

standard platinum- and- taxane regimens used frequently

for other types of ovarian cancer. Gastrointestinal cancer

regimens are another option; these include 5- uorouracil

and oxaliplatin, or capecitabine and oxaliplatin. Data

on heated intra- peritoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) for

mucinous ovarian cancer are scarce, but HIPEC may

be worth considering. For patients with recurrence or

progression on rst- line chemotherapy, we advocate

enrollment in a clinical trial if one is available. For this

reason, it may be benecial to perform molecular testing in

all patients with recurrent or progressive mucinous ovarian

cancer.

BACKGROUND

Primary mucinous ovarian cancer is a rare malignancy

accounting for <3% of all epithelial ovarian cancers.

1

Because of its rarity, primary mucinous ovarian cancer

has historically been under- represented in clinical

trials for epithelial ovarian cancer, meaning that the

evidence base for treatment for primary mucinous

ovarian cancer is not strong. What has become clear

is that mucinous ovarian cancer is distinct from the

more common epithelial ovarian cancer types, such

as serous ovarian cancer, in terms of clinical behavior

and response to chemotherapy. For example, 83%

of patients with primary mucinous ovarian cancer

have ovary- conned disease at diagnosis compared

with only 4% of patients with serous ovarian cancer.

2

Patients with stage I primary mucinous ovarian cancer

have a 5- year overall survival rate approaching 90%.

3

In contrast, patients with stage II–IV disease have a

much worse prognosis than women with metastatic

serous ovarian cancer at similar stages treated with

similar chemotherapy regimens.

4 5

We review surgical and chemotherapy options for

women with primary mucinous ovarian cancer and

offer recommendations for treating women with this

disease.

EVALUATION AT DIAGNOSIS

Given the rarity of this tumor type, patients with a

new diagnosis of mucinous ovarian cancer should

have a thorough evaluation to rule out a gastroin-

testinal primary tumor. In two separate Gynecologic

Oncology Group studies, the majority of cases that

were initially thought to be mucinous ovarian carci-

noma were reclassied as gastrointestinal primary

tumors on re- review of the pathologic specimens

(55% in Gore et al and 57–63% in Zaino et al).

6 7

Although data regarding site of origin are not avail-

able from this study, another analysis of the published

literature suggested that colorectal primaries are the

most common gastrointestinal source, followed by

gastric, appendiceal, and pancreatic.

8

Thus, review of

the specimens by a gynecologic pathologist is critical.

Colonoscopy and upper gastrointestinal endoscopy

should also be performed to rule out a gastrointestinal

primary tumor.

Computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen,

and pelvis should be performed for baseline staging,

as for other types of ovarian cancer. The tumor

markers CA125, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and

CA19- 9 may all be useful in the diagnosis and surveil-

lance of mucinous ovarian tumors

9–13

and should be

evaluated at baseline. A ratio of CA125 level to CEA

level of >25 to 1 may be indicative of a gynecologic

primary tumor, although the positive predictive value

on August 30, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://ijgc.bmj.com/Int J Gynecol Cancer: first published as 10.1136/ijgc-2022-003806 on 13 October 2022. Downloaded from

1456

KurnitKC, FrumovitzM. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2022;32:1455–1462. doi:10.1136/ijgc-2022-003806

Review

is only 82%.

14

Unfortunately, mucinous ovarian cancer often is not

diagnosed until after surgery, at which time levels of tumor markers

may be normal even if they were elevated at baseline.

PATHOLOGIC FEATURES

The 2014 World Health Organization classication system sepa-

rates primary mucinous ovarian cancer into two sub- types: expan-

sile (conuent) and inltrative. Although available data are limited,

a recent review of the literature suggests that 50–60% of reported

mucinous ovarian tumors may exhibit inltrative histology.

15

Expan-

sile tumors exhibit conuent glandular growth with little or no inter-

vening stroma and no stromal invasion. These tumors have low

metastatic potential and are limited to the ovary in 95% of cases.

Furthermore, among patients with the expansile sub- type, <5% of

patients with stage I disease have recurrence. In contrast, inltrative

tumors have destructive stromal invasion with haphazard glands

and associated desmoplastic stromal reaction. These tumors are

more aggressive, and although 75% are stage I at diagnosis, in

15–30% of women with stage I disease they will recur.

15

Both

expansile and inltrative mucinous ovarian cancers usually stain

diffusely positive for CK7. They may also stain positive for CK20,

PAX- 8, and/or estrogen receptor, but when they stain positive, the

pattern of staining is focal or patchy, not diffuse. This contrasts with

the pattern observed in metastatic colorectal carcinoma, which

typically stains diffusely positive for CK20 and negative for CK7.

16

Tumor size and laterality may be helpful in differentiating primary

mucinous ovarian cancer from metastatic disease from a gastroin-

testinal tumor. If the tumor is unilateral and >10 cm in diameter, the

ovary is the primary tumor site in >80% of cases. If the tumor is

bilateral and/or <10 cm in diameter, the primary tumor site is in the

gastrointestinal tract in >90% of cases.

2

SURGICAL TREATMENT

Primary Treatment

Surgical management of primary mucinous ovarian cancer largely

mirrors surgical management of other types of epithelial ovarian

cancer. This typically includes a total hysterectomy, bilateral

salpingo- oophorectomy, omentectomy, and removal of any visible

tumor metastases with the goal of complete gross resection of

disease. When possible, surgery for mucinous ovarian cancer should

be performed by gynecologic oncologists. Traditionally, staging and

debulking procedures were done via laparotomy. More recently, use

of minimally invasive approaches has increased, most commonly

in patients with an isolated pelvic mass. When minimally invasive

surgery is used, care should be taken to avoid intra- abdominal

rupture and spillage, which increases the nal disease stage.

Staging Procedures

Even in patients with disease apparently conned to the pelvis,

occult peritoneal disease has been described in mucinous ovarian

carcinomas.

17

At a minimum, staging should include pelvic wash-

ings, omentectomy, and peritoneal biopsies. The role of lymphad-

enectomy is less certain in mucinous ovarian carcinoma than in

high- grade serous ovarian carcinoma. Historically, complete pelvic

and para- aortic lymphadenectomies were performed. In the 2010s,

data were published suggesting that the frequency of lymph node

metastasis in mucinous ovarian cancer is very low (0–2%),

18–21

and

thus lymphadenectomy in patients with grossly normal appearing

lymph nodes was frequently omitted. However, new data emerged

showing that, although lymph node metastases are rare in expansile

mucinous ovarian cancer, lymph node metastases may be present

in up to 30% of patients with the inltrative sub- type.

17 22

Thus, in

general, lymph node evaluation should be considered in patients

with inltrative tumors. From a practical standpoint, however, it

is difcult to determine the sub- type of mucinous ovarian cancer

intra- operatively. Frozen section analysis of mucinous ovarian

tumors is notoriously difcult, and one study indicated that the nal

diagnosis (benign vs borderline vs invasive mucinous carcinoma)

might differ from the diagnosis rendered on the basis of frozen

section evaluation in 10% of cases.

23

More realistically, knowledge

of the sub- type of mucinous ovarian cancer—inltrative or expan-

sile—may be more useful when the patient has already undergone

unilateral oophorectomy and the decision is being made whether to

re- operate for staging purposes.

Further research is needed into strategies for improving intra-

operative diagnosis and decision- making, and a staged procedure

may ultimately be required if a diagnosis cannot be conrmed

intra- operatively during the initial surgical procedure.

Appendectomy

Another intra- operative consideration is whether or not appendec-

tomy should be routinely performed. Previously, routine appen-

dectomy was recommended for any patient with a borderline or

invasive mucinous ovarian cancer to ensure that the appendix was

not the true primary tumor site. Most recent data suggest, however,

that the likelihood of an occult appendiceal primary tumor in a

patient with a normal- appearing appendix is of the order of 1% or

less.

17 24–26

Thus, we recommend that the appendix be routinely

evaluated intra- operatively, but an appendectomy may be omitted if

the appendix appears grossly normal, particularly if no gross meta-

static disease is identied.

Fertility Preservation

In primary mucinous ovarian cancer, as in other types of epithe-

lial ovarian cancer, fertility preservation with unilateral salpingo-

oophorectomy can be considered in patients with disease conned

to one ovary, who have a normal- appearing contralateral ovary, and

who desire future fertility. Given that the median age at diagnosis

is lower for patients with mucinous ovarian cancer than for those

with other types of epithelial ovarian cancer,

27 28

and given the

good prognosis for many patients with stage I mucinous ovarian

cancer,

3

desire for fertility preservation among these patients is not

uncommon. Data regarding the safety of fertility preservation are

limited, but overall small series have not shown a clear increased

risk of recurrence or death with fertility- sparing approaches.

28–31

In

these small series, some but not all patients had surgical staging

with biopsies, omentectomy, and/or lymphadenectomy, which also

makes these data more difcult to interpret. Median age at diag-

nosis for patients included in these studies was largely in the late

20s. Given the limitations of available data, patients should be care-

fully counseled about the theoretical increased risk of recurrence,

28

particularly in the case of inltrative disease.

31

However, overall for

on August 30, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://ijgc.bmj.com/Int J Gynecol Cancer: first published as 10.1136/ijgc-2022-003806 on 13 October 2022. Downloaded from

1457

KurnitKC, FrumovitzM. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2022;32:1455–1462. doi:10.1136/ijgc-2022-003806

Review

surgically staged patients desiring fertility preservation, fertility-

sparing surgeries could be considered.

Treatment of Recurrent Disease

Data regarding surgical interventions for recurrent mucinous ovarian

carcinoma are largely extrapolated from other types of epithelial

ovarian cancer. Several recent trials suggested that secondary

debulking may be benecial for patients in whom the likelihood of

achieving a complete gross resection is high,

32 33

although notably

one study that included bevacizumab did not show any survival

benet for secondary debulking.

34

It is worth noting, however, that

very few patients with mucinous ovarian cancer were included in

these studies. In general, though, patients with platinum- sensitive

disease whose disease distribution suggests a high likelihood

of complete gross resection may be candidates for secondary

debulking. Furthermore, given the poor rates of response to systemic

treatment (discussed below), we believe secondary cytoreduction

may prove to be more benecial in patients with mucinous ovarian

cancer than in patients with other types of epithelial ovarian cancer.

SYSTEMIC TREATMENT

Primary Treatment

Historically, patients with mucinous ovarian cancer were included

in large practice- changing trials of systemic treatment for other

types of epithelial ovarian cancer. For this reason, until recently,

standard rst- line adjuvant systemic treatment for patients with

mucinous ovarian cancer included the doublet of carboplatin and

paclitaxel, with consideration of adding bevacizumab for patients

with advanced disease. However, given the rarity of this histologic

type, patients with mucinous ovarian cancer frequently accounted

for only 7% or fewer of the patients in these large trials.

12 35–39

Additionally, mucinous ovarian cancer behaves markedly differ-

ently from high- grade serous ovarian cancer,

7

the type that is most

widely represented in these studies. Thus, it is uncertain whether

results from these landmark trials can truly be extrapolated to

patients with mucinous ovarian cancer.

The poorer prognosis seen with mucinous ovarian cancer relative

to high- grade serous ovarian cancer is thought to be due at least in

part to the lower degree of platinum sensitivity of mucinous ovarian

cancer. Platinum sensitivity data are largely based on retrospec-

tive studies. One such study, a case–control study that included

27 patients with advanced mucinous ovarian cancer, showed a

response rate of 26% for these patients compared with 65% in

patients with other types of epithelial ovarian cancer (the control

group).

4

A second retrospective study found that the response rate

to rst- line platinum- based chemotherapy was 39% for patients

with advanced- stage mucinous ovarian cancer compared with 70%

for patients with serous ovarian cancer.

40

In a third small study of

21 patients with newly diagnosed mucinous ovarian cancer, only

32% of evaluable patients had a complete response to rst- line

platinum- based chemotherapy and an additional 11% had a partial

response; 47% had disease progression.

10

Given these poor response rates and the histologic similarity

between primary mucinous ovarian tumors and mucinous tumors

of the gastrointestinal tract, the hypothesis arose that mucinous

ovarian tumors may respond better to gastrointestinal chemo-

therapy regimens. On the basis of pre- clinical data supporting this

hypothesis,

41

a phase II trial comparing a gastrointestinal cancer

regimen with a traditional gynecologic cancer regimen in patients

with mucinous ovarian cancer was implemented. Gynecologic

Oncology Group trial 241/mEOC randomized patients to one of

four arms: capecitabine and oxaliplatin; capecitabine, oxaliplatin,

and bevacizumab; carboplatin and paclitaxel; or carboplatin, pacl-

itaxel, and bevacizumab.

6

The planned accrual was 330 patients,

and enrollment occurred in both the USA and the UK. Unfortunately,

the study closed early, in large part because of poor accrual. This

highlights one of the major barriers to clinical trials of rare tumor

types: accrual is very difcult and frequently requires many years of

enrollment even when the trial is open nationwide or internationally.

On analyses of the enrolled patients, the investigators also iden-

tied a second signicant issue: 55% of the patients were found

to have a non- gynecologic primary mucinous tumor on central

pathology review.

6

This nding limited the conclusions that could

be drawn. However, the data that were available suggested that

gastrointestinal cancer regimens were not worse than gynecologic

cancer regimens, even when the analysis was limited to the sub-

set of patients in whom an ovarian primary tumor was conrmed.

Following these results, the results from two other retrospective

studies were published. The rst was a descriptive study of 21

patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy with either a gastro-

intestinal cancer regimen (n=9) or a gynecologic cancer regimen

(n=12).

42

No difference was seen between the two regimens but,

of note, the stage distributions for the two regimens were unbal-

anced with those receiving the gastrointestinal cancer regimen

having more advanced disease. The second study, a retrospective

cohort study from two tertiary referral centers, evaluated the use of

gynecologic cancer (n=26) and gastrointestinal cancer regimens

(n=26) as rst- line treatment for patients with mucinous ovarian

cancer. The results of this second study demonstrated a signicant

improvement in overall survival for patients who received gastro-

intestinal cancer regimens, primarily 5- uorouracil and oxaliplatin

or capecitabine and oxaliplatin, with or without bevacizumab.

43

On

the basis of these limited data, as well as the overall biological

rationale and the poor outcomes seen for patients with advanced

mucinous ovarian cancer, the National Comprehensive Cancer

Network (NCCN) has updated their recommendations for rst- line

treatment for mucinous ovarian cancer to include 5- uorouracil

and oxaliplatin, capecitabine and oxaliplatin, and carboplatin and

paclitaxel.

44

Recommendations for which patients with mucinous ovarian

cancer would benet most from adjuvant treatment are varied.

Most organizations agree that patients with stage II, III, or IV disease

should receive adjuvant treatment. In general, outcomes for this

group of patients remain poor.

28

The use of adjuvant treatment was

supported by a recent database study of patients with stages II–IV

mucinous ovarian cancer that showed an improvement in overall

survival for those who received chemotherapy.

45

However, recom-

mendations for patients with stage I disease are mixed. NCCN

recommends that patients with stage IC disease receive adjuvant

chemotherapy and that those with stage IA or IB disease do not,

regardless of other histologic ndings.

44

In contrast, the European

Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines recommend that

treatment decisions for stage I disease be based at least in part

on the histologic sub- type, as inltrative tumors tend to behave

more aggressively than expansile tumors.

46

The ESMO guidelines

on August 30, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://ijgc.bmj.com/Int J Gynecol Cancer: first published as 10.1136/ijgc-2022-003806 on 13 October 2022. Downloaded from

1458

KurnitKC, FrumovitzM. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2022;32:1455–1462. doi:10.1136/ijgc-2022-003806

Review

recommend against adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with stage

IA expansile, grade 1–2 tumors. For all other sub- groups of patients

with stage I disease, the ESMO guidelines either state that chemo-

therapy should be considered (for patients with stage IA inltrative

tumors or stage IB or IC expansile tumors) or state that chemo-

therapy is recommended (for patients with stage IB or IC inltrative

tumors). A recent study from the National Cancer Database found

no improvement in overall survival for patients with stage I disease

who received adjuvant chemotherapy.

3

However, in that report,

the authors provided no information about histologic sub- groups.

A different study from the National Cancer Database attempted

to further characterize patients with stage I disease into higher-

and lower- risk groups, but notably also did not include information

about inltrative or expansile histology.

47

The differences in recom-

mendations regarding adjuvant chemotherapy for primary muci-

nous ovarian cancer reect the limited data that are available and

highlight an area where further investigation would be benecial.

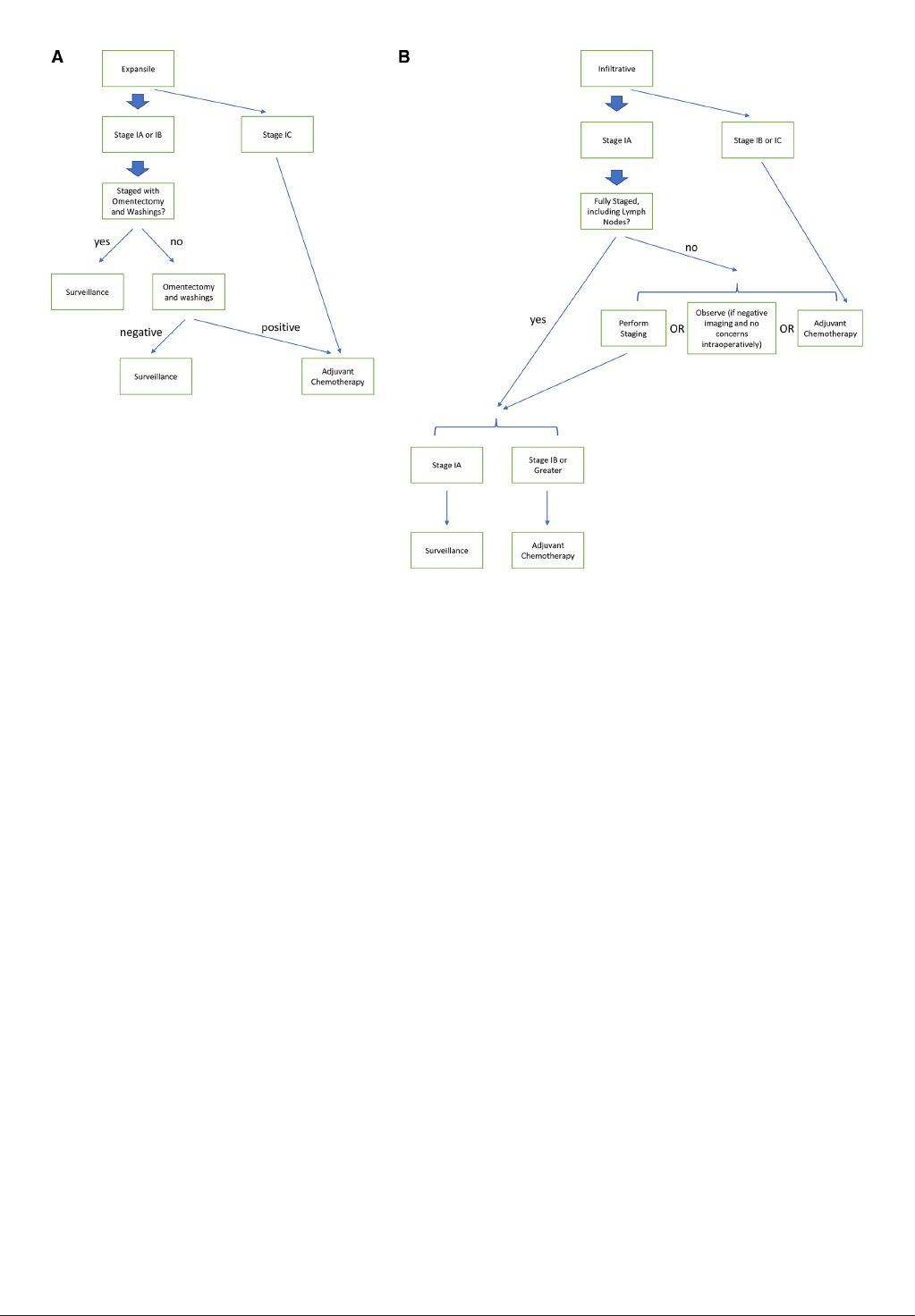

Incorporating these ndings, we would recommend erring on the

side of complete staging for patients with clinical stage I mucinous

ovarian cancer with inltrative histology. Our proposed approach is

outlined in Figure1.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy might be appropriate for certain

patients with advanced stage mucinous ovarian cancer, with

patient selection for treatment based on algorithms for other

types of ovarian cancer

44

; however, neoadjuvant chemotherapy for

mucinous ovarian cancer remains understudied. Within the three

largest trials of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for ovarian cancer, no

more than 3% of patients had a diagnosis of mucinous ovarian

cancer.

48–50

Therefore, the safety and efcacy of neoadjuvant

chemotherapy with interval debulking surgeries in patients with

mucinous ovarian cancer remain unknown. Furthermore, it is

uncertain whether traditional gynecologic cancer regimens should

be used, or whether these patients would benet from gastrointes-

tinal cancer regimens, as discussed above. A nal consideration is

that diagnosing the primary tumor site for mucinous tumors may

be more difcult with a core biopsy and limited tissue than when

the entire ovary can be examined. Thus, in cases of metastatic

mucinous disease in which the primary tumor site of origin is not

clear, we recommend review in collaboration with a gastrointes-

tinal oncology team. However, outcomes for metastatic mucinous

carcinoma, regardless of whether it arises from a gynecologic or

gastrointestinal primary tumor, are overall poor.

7

Heated Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy (HIPEC)

Whether or not heated intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) may

be benecial for patients with epithelial ovarian cancer has been

increasingly discussed. A study by van Driel et al in the Netherlands

showed a recurrence- free and overall survival benet from HIPEC

at the time of interval debulking for patients with stage III epithelial

ovarian cancer.

51

In contrast, a phase II trial at the Memorial Sloan

Kettering Cancer Center in the USA, which evaluated the use of

HIPEC for recurrent platinum- sensitive high- grade serous ovarian

cancer, did not nd a benet.

52

The utility of HIPEC for recurrent

high- grade serous ovarian cancer therefore remains uncertain.

Data on the use of HIPEC in patients with mucinous ovarian cancer

are currently limited. Notably, the study by van Driel et al cited

above included only three patients with mucinous ovarian cancer

among a total of 245 patients enrolled.

51

Despite these limited data,

there remains substantial interest in the use of HIPEC in patients

with mucinous ovarian cancer because of the disease’s similarity to

gastrointestinal tumors, in which HIPEC is often used to treat carci-

nomatosis.

53

The Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International

Figure 1 Treatment algorithm for stage I mucinous ovarian cancer tumors with (A)expansile or (B)inltrative sub- types.

on August 30, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://ijgc.bmj.com/Int J Gynecol Cancer: first published as 10.1136/ijgc-2022-003806 on 13 October 2022. Downloaded from

1459

KurnitKC, FrumovitzM. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2022;32:1455–1462. doi:10.1136/ijgc-2022-003806

Review

and BIG- RENAPE working groups in France published their expe-

rience with the use of HIPEC in rare ovarian tumors. They found a

particular benet in patients with mucinous ovarian cancer; in this

group, neither the median progression- free survival nor the median

overall survival had been reached by 5 years (n=77).

54

Patients with

mucinous ovarian cancer in this study had perfusion with either

mitomycin C or oxaliplatin, which is the working groups’ standard

treatment for appendiceal tumors.

55

In contrast, all patients in the

study by van Driel et al had perfusion with cisplatin.

51

A group from China published their experience with patients

diagnosed with pseudomyxoma peritonei secondary to mucinous

ovarian cancer.

56

Over a 10- year period they performed cytoreduc-

tion and HIPEC in 22 patients. Similar to van Driel et al, this group

used cisplatin for perfusion. Patients with low- grade mucinous

cancers and those with lower peritoneal cancer index scores had

improved overall survival. Notably, median overall survival times

were shorter than 40 months for the entire cohort of patients with

pseudomyxoma peritonei due to mucinous ovarian cancer in this

study.

56

Much remains unanswered about the role of HIPEC in mucinous

ovarian cancer. Additionally, recent data about the use of HIPEC in

colorectal cancer did not show the benets anticipated,

57

implying

that there is still much to be understood about HIPEC in general.

However, given the rarity of mucinous ovarian cancer and the

lack of effective systemic treatment options, HIPEC may be worth

considering. Whether HIPEC is best given at the time of initial diag-

nosis, as a second staging surgery following the initial diagnosis in

the up- front setting, or at the time of secondary debulking is not

clear. Given that that vast majority of mucinous ovarian cancers

are stage I at diagnosis and do not recur, it is likely that primary

treatment with HIPEC for all patients with newly diagnosed muci-

nous ovarian cancer would result in overtreatment in a substantial

proportion of patients. Thus, it may make most sense to preserve

HIPEC for tumors associated with highest risk: those that are meta-

static at diagnosis or those that have already recurred. We hope

that future trials will better delineate the optimal use of HIPEC in

patients with mucinous ovarian cancer.

Treatment of Recurrent and Progressive Disease

Data on second- line systemic treatment for mucinous ovarian

cancer are even more limited than data on rst- line systemic treat-

ment. A retrospective study evaluated 20 patients with mucinous

ovarian cancer who had a recurrence at least 6 months after their

initial treatment.

9

Although the number of patients in this study

was small, several patients treated with platinum as second-

line chemotherapy had a response. No patient treated with non-

platinum agents as second- line chemotherapy had a response.

Among patients treated with third- or fourth- line chemotherapy,

one patient had a response to paclitaxel, topotecan, and cyclophos-

phamide as third- line treatment, and one patient had a response

to this regimen as fourth- line treatment, but no responses were

seen to gemcitabine or liposomal doxorubicin.

9

Another small study

found that none of the 12 patients treated in second line or beyond

with cytotoxic chemotherapy had a complete response, and only

one and two patients had partial and complete responses, respec-

tively, to second- line treatment. The remaining eight patients in the

second- line setting and six patients in the third- line setting all had

progression of disease.

10

Bevacizumab may also be benecial for treatment of recurrent or

progressive disease. One case report described a patient with recur-

rence after adjuvant carboplatin and paclitaxel followed by several

standard single- agent regimens for platinum- resistant disease.

She was treated with weekly paclitaxel with bevacizumab for six

cycles, followed by maintenance bevacizumab for 32 cycles, and

she had a durable response to treatment (stable disease).

58

Another

case report described durable disease stabilization of a borderline

mucinous ovarian tumor with single- agent bevacizumab.

59

In general, responses to standard- of- care chemotherapy at the

time of recurrence or progression of mucinous ovarian cancer

are relatively poor. Other regimens for platinum- resistant ovarian

cancer listed in the NCCN guidelines should be considered. For

patients who received combinations of platinum agents and

taxanes for adjuvant treatment, there may be benet to attempting

a gastrointestinal cancer regimen such as capecitabine and oxal-

iplatin or 5- uorouracil and oxaliplatin. However, given the poor

outcomes described above, even for patients who previously

received gastrointestinal cancer regimens, it may also be benecial

to extrapolate from data on mucinous gastrointestinal tumors and

consider second- line gastrointestinal cancer regimens, particularly

in patients whose functional status remains good after receipt of

multiple other lines of treatment. Further data are needed to explore

the question of whether the sequence of regimens matters and

which second- line regimens are most likely to be successful.

Molecular Characterization and Novel Agents

Given the poor response of mucinous ovarian cancer to cytotoxic

chemotherapy, there is much interest in further exploring novel

agents for this rare tumor type. Large molecular studies have

shown that mucinous ovarian cancers often have aberrations in

TP53 (57–90%), KRAS (44–79%), and CDKN2A (11–19%).

60–64

Her2 positivity or ERBB2 amplication has also been demonstrated

in 18–27% of mucinous ovarian cancers.

62 63 65 66

Mismatch repair deciency has been reported in mucinous

ovarian cancer, although it is a rare event.

60 67

Thus, the tumor-

type agnostic approval of pembrolizumab for patients with tumors

demonstrating mismatch repair deciency or high microsatel-

lite instability

68 69

provides another viable option for treatment of

recurrent disease. Homologous recombination deciency, which is

present in up to 50% of high- grade serous ovarian cancers,

70

is

rare in mucinous ovarian tumors.

67

Her2 positivity may be targetable given its prevalence described

above, although data about treatment options for Her2- positive

disease are limited. Extrapolating from other tumor types, it may

be possible to combine Her2- targeting treatment with standard- of-

care chemotherapy (trastuzumab plus carboplatin and paclitaxel

71

)

or to give Her2- targeting treatment as a single agent. Additionally,

the combination of trastuzumab and pertuzumab is currently being

explored in other tumor types with Her2 positivity,

72 73

and while this

combination has not been evaluated in mucinous ovarian cancer, it

may represent an avenue for future exploration.

Estrogen and progesterone receptor positivity has also been

reported in a sub- set of patients with mucinous ovarian cancer

in one study,

67 74

and thus anti- hormonal agents could be consid-

ered for selected patients. Novel agents targeting the Ras pathway

are currently in use for other tumor types and may be a prom-

ising avenue in the future. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)

on August 30, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://ijgc.bmj.com/Int J Gynecol Cancer: first published as 10.1136/ijgc-2022-003806 on 13 October 2022. Downloaded from

1460

KurnitKC, FrumovitzM. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2022;32:1455–1462. doi:10.1136/ijgc-2022-003806

Review

inhibitors have also been proposed,

75

and other new treatments are

being explored in pre- clinical studies.

76–80

While data are lacking

for many of these novel agents, we hope that patients with muci-

nous ovarian cancers will be enrolled in future basket trials of

these targeted therapies as it is unlikely that a biomarker- driven,

tumor type- specic trial of treatment for this rare histologic sub-

type could achieve adequate accrual. If a patient has recurrence or

progression on rst- line chemotherapy, we would advocate enroll-

ment in a clinical trial if one is available. For this reason, it may be

benecial to perform molecular testing, including next- generation

sequencing, mismatch repair deciency, and Her2 testing, in all

patients with recurrent or progressive mucinous ovarian cancer.

CONCLUSIONS

Metastatic mucinous ovarian cancer is a rare but aggressive type

of epithelial ovarian cancer. Given its rarity, large prospective

studies of treatment for this disease have been difcult. This review

summarizes the available data and highlights areas that warrant

future investigation. Many patients are diagnosed at an early stage

and outcomes in this setting are better; however, identifying the

ideal algorithms for patients with early- stage inltrative disease

has been difcult. Similarly, surgical management may need to

differ depending on histologic ndings, so developing ways that

details about the histologic sub- type can be available at the time of

a surgical staging procedure could be important. Although systemic

treatment is recommended for all patients with metastatic muci-

nous ovarian cancer, data are still limited on whether a traditional

gynecologic regimen is sufcient or whether a gastrointestinal

regimen may be benecial. Fully dening the role of HIPEC and

knowledge about which second- line regimens are most effective

have also remained elusive. New therapies and updated treat-

ment algorithms are sorely needed, and we may need to rely on

novel clinical trial designs and basket trial approaches in order to

obtain the data we need to move the eld forward for this sub- set

of patients.

Twitter Michael Frumovitz @frumovitz

Contributors KK: concept development, literature search, writing, revisions,

guarantor. MF: concept development, literature search, writing, revisions.

Funding The authors have not declared a specic grant for this research from any

funding agency in the public, commercial or not- for- prot sectors.

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent for publication Not applicable.

Ethics approval Not applicable.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

ORCID iDs

Katherine CKurnit http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3205-0128

MichaelFrumovitz http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0810-2648

REFERENCES

1 Seidman JD, Horkayne- Szakaly I, Haiba M, etal. The histologic type

and stage distribution of ovarian carcinomas of surface epithelial

origin. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2004;23:41–4.

2 Seidman JD, Kurman RJ, Ronnett BM. Primary and metastatic

mucinous adenocarcinomas in the ovaries: incidence in routine

practice with a new approach to improve intraoperative diagnosis.

Am J Surg Pathol 2003;27:985–93.

3 Nasioudis D, Haggerty AF, Giuntoli RL, etal. Adjuvant chemotherapy

is not associated with a survival benet for patients with early stage

mucinous ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 2019;154:302–7.

4 Hess V, A'Hern R, Nasiri N, etal. Mucinous epithelial ovarian

cancer: a separate entity requiring specic treatment. J Clin Oncol

2004;22:1040–4.

5 Winter WE, Maxwell GL, Tian C, etal. Prognostic factors for stage III

epithelial ovarian cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study.

J Clin Oncol 2007;25:3621–7.

6 Gore M, Hackshaw A, Brady WE, etal. An international, phase III

randomized trial in patients with mucinous epithelial ovarian cancer

(mEOC/GOG 0241) with long- term follow- up: and experience of

conducting a clinical trial in a rare gynecological tumor. Gynecol

Oncol 2019;153:541–8.

7 Zaino RJ, Brady MF, Lele SM, etal. Advanced stage mucinous

adenocarcinoma of the ovary is both rare and highly lethal: a

Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Cancer 2011;117:554–62.

8 Dundr P, Singh N, Nožičková B, etal. Primary mucinous ovarian

tumors vs. ovarian metastases from gastrointestinal tract, pancreas

and biliary tree: a review of current problematics. Diagn Pathol

2021;16:20.

9 Pignata S, Ferrandina G, Scarfone G, etal. Activity of chemotherapy

in mucinous ovarian cancer with a recurrence free interval of more

than 6 months: results from the SOCRATES retrospective study.

BMC Cancer 2008;8:252.

10 Pisano C, Greggi S, Tambaro R, etal. Activity of chemotherapy in

mucinous epithelial ovarian cancer: a retrospective study. Anticancer

Res 2005;25:3501–5.

11 McCluggage WG. Immunohistochemistry in the distinction between

primary and metastatic ovarian mucinous neoplasms. J Clin Pathol

2012;65:596–600.

12 Xu W, Rush J, Rickett K, etal. Mucinous ovarian cancer: a

therapeutic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2016;102:26–36.

13 Kelly PJ, Archbold P, Price JH, etal. Serum CA19.9 levels are

commonly elevated in primary ovarian mucinous tumours but

cannot be used to predict the histological subtype. J Clin Pathol

2010;63:169–73.

14 Sørensen SS, Mosgaard BJ. Combination of cancer antigen 125 and

carcinoembryonic antigen can improve ovarian cancer diagnosis.

Dan Med Bull 2011;58:A4331.

15 Morice P, Gouy S, Leary A. Mucinous ovarian carcinoma. N Engl J

Med 2019;380:1256–66.

16 Babaier A, Ghatage P. Mucinous cancer of the ovary: overview

and current status. Diagnostics 2020;10. doi:10.3390/

diagnostics10010052. [Epub ahead of print: 19 01 2020].

17 Gouy S, Saidani M, Maulard A, etal. Staging surgery in early- stage

ovarian mucinous tumors according to expansile and inltrative

types. Gynecol Oncol Rep 2017;22:21–5.

18 Schmeler KM, Tao X, Frumovitz M, etal. Prevalence of lymph node

metastasis in primary mucinous carcinoma of the ovary. Obstet

Gynecol 2010;116:269–73.

19 Salgado- Ceballos I, Ríos J, Pérez- Montiel D, etal. Is

lymphadenectomy necessary in mucinous ovarian cancer? A single

institution experience. Int J Surg 2017;41:1–5.

20 van Baal J, Van de Vijver KK, Coffelt SB, etal. Incidence of lymph

node metastases in clinical early- stage mucinous and seromucinous

ovarian carcinoma: a retrospective cohort study. BJOG

2017;124:486–94.

21 Hoogendam JP, Vlek CA, Witteveen PO, etal. Surgical lymph node

assessment in mucinous ovarian carcinoma staging: a systematic

review and meta- analysis. BJOG 2017;124:370–8.

22 Muyldermans K, Moerman P, Amant F, etal. Primary invasive

mucinous ovarian carcinoma of the intestinal type: importance of the

expansile versus inltrative type in predicting recurrence and lymph

node metastases. Eur J Cancer 2013;49:1600–8.

23 Park JY, Lee SH, Kim KR, etal. Accuracy of frozen section diagnosis

and factors associated with nal pathological diagnosis upgrade of

mucinous ovarian tumors. J Gynecol Oncol 2019;30:e95.

24 Lin JE, Seo S, Kushner DM, etal. The role of appendectomy for

mucinous ovarian neoplasms. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013;208:46

e1–4.

25 Ozcan A, Töz E, Turan V, etal. Should we remove the normal-

looking appendix during operations for borderline mucinous

ovarian neoplasms? A retrospective study of 129 cases. Int J Surg

2015;18:99–103.

26 Cheng A, Li M, Kanis MJ, etal. Is it necessary to perform routine

appendectomy for mucinous ovarian neoplasms? A retrospective

study and meta- analysis. Gynecol Oncol 2017;144:215–22.

27 Peres LC, Cushing- Haugen KL, Köbel M, etal. Invasive epithelial

ovarian cancer survival by histotype and disease stage. J Natl

Cancer Inst 2019;111:60–8.

on August 30, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://ijgc.bmj.com/Int J Gynecol Cancer: first published as 10.1136/ijgc-2022-003806 on 13 October 2022. Downloaded from

1461

KurnitKC, FrumovitzM. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2022;32:1455–1462. doi:10.1136/ijgc-2022-003806

Review

28 Mueller JJ, Lajer H, Mosgaard BJ, etal. International study of

primary mucinous ovarian carcinomas managed at tertiary medical

centers. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2018;28:915–24.

29 Lee J- Y, Jo YR, Kim TH, etal. Safety of fertility- sparing surgery

in primary mucinous carcinoma of the ovary. Cancer Res Treat

2015;47:290–7.

30 Gouy S, Saidani M, Maulard A, etal. Results of fertility- sparing

surgery for expansile and inltrative mucinous ovarian cancers.

Oncologist 2018;23:324–7.

31 Gouy S, Saidani M, Maulard A, etal. Is uterine preservation

combined with bilateral salpingo- oophorectomy to promote

subsequent fertility safe in inltrative mucinous ovarian cancer?

Gynecol Oncol Rep 2017;22:52–4.

32 Shi T, Zhu J, Feng Y, etal. Secondary cytoreduction followed by

chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone in platinum- sensitive

relapsed ovarian cancer (SOC- 1): a multicentre, open- label,

randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2021;22:439–49.

33 Harter P, Sehouli J, Vergote I, etal. Randomized trial of

cytoreductive surgery for relapsed ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med

2021;385:2123–31.

34 Coleman RL, Spirtos NM, Enserro D, etal. Secondary surgical

cytoreduction for recurrent ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med

2019;381:1929–39.

35 Perren TJ, Swart AM, Psterer J, etal. A phase 3 trial of

bevacizumab in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 2011;365:2484–96.

36 McGuire WP, Hoskins WJ, Brady MF, etal. Cyclophosphamide and

cisplatin compared with paclitaxel and cisplatin in patients with

stage III and stage IV ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 1996;334:1–6.

37 Muggia FM, Braly PS, Brady MF, etal. Phase III randomized study of

cisplatin versus paclitaxel versus cisplatin and paclitaxel in patients

with suboptimal stage III or IV ovarian cancer: a Gynecologic

Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:106–15.

38 Neijt JP, Engelholm SA, Tuxen MK, etal. Exploratory phase III study

of paclitaxel and cisplatin versus paclitaxel and carboplatin in

advanced ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:3084–92.

39 International Collaborative Ovarian Neoplasm Group. Paclitaxel plus

carboplatin versus standard chemotherapy with either single- agent

carboplatin or cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in

women with ovarian cancer: the ICON3 randomised trial. Lancet

2002;360:505–15.

40 Pectasides D, Fountzilas G, Aravantinos G, etal. Advanced stage

mucinous epithelial ovarian cancer: the Hellenic Cooperative

Oncology Group experience. Gynecol Oncol 2005;97:436–41.

41 Sato S, Itamochi H, Kigawa J, etal. Combination chemotherapy

of oxaliplatin and 5- uorouracil may be an effective regimen for

mucinous adenocarcinoma of the ovary: a potential treatment

strategy. Cancer Sci 2009;100:546–51.

42 Schlappe BA, Zhou QC, O'Cearbhaill R, etal. A descriptive report

of outcomes of primary mucinous ovarian cancer patients receiving

either an adjuvant gynecologic or gastrointestinal chemotherapy

regimen. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2019. doi:10.1136/ijgc-2018-000150.

[Epub ahead of print: 15 May 2019].

43 Kurnit KC, Sinno AK, Fellman BM, etal. Effects of gastrointestinal-

type chemotherapy in women with ovarian mucinous carcinoma.

Obstet Gynecol 2019;134:1253–9.

44 National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Ovarian cancer including

fallopian tube cancer and primary peritoneal cancer (version 1.2022);

2022.

45 Nasioudis D, Albright BB, Ko EM, etal. Advanced stage primary

mucinous ovarian carcinoma. Where do we stand ? Arch Gynecol

Obstet 2020;301:1047–54.

46 Colombo N, Sessa C, du Bois A, etal. ESMO- ESGO consensus

conference recommendations on ovarian cancer: pathology and

molecular biology, early and advanced stages, borderline tumours

and recurrent disease†. Ann Oncol 2019;30:672–705.

47 Richardson MT, Mysona DP, Klein DA, etal. Long term survival

outcomes of stage I mucinous ovarian cancer - a clinical

calculator predictive of chemotherapy benet. Gynecol Oncol

2020;159:118–28.

48 Kehoe S, Hook J, Nankivell M, etal. Primary chemotherapy versus

primary surgery for newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer

(CHORUS): an open- label, randomised, controlled, non- inferiority

trial. Lancet 2015;386:249–57.

49 Vergote I, Tropé CG, Amant F, etal. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy

or primary surgery in stage IIIC or IV ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med

2010;363:943–53.

50 Fagotti A, Ferrandina MG, Vizzielli G, etal. Randomized trial of

primary debulking surgery versus neoadjuvant chemotherapy for

advanced epithelial ovarian cancer (SCORPION- NCT01461850). Int

J Gynecol Cancer 2020;30:1657–64.

51 van Driel WJ, Koole SN, Sikorska K, etal. Hyperthermic

intraperitoneal chemotherapy in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med

2018;378:230–40.

52 Zivanovic O, Chi DS, Zhou Q, etal. Secondary cytoreduction and

carboplatin hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for platinum-

sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer: an MSK team ovary phase II

study. J Clin Oncol 2021;39:2594–604.

53 Iavazzo C, Spiliotis J. Is there a promising role of HIPEC in patients

with advanced mucinous ovarian cancer? Arch Gynecol Obstet

2021;303:597–8.

54 Mercier F, Bakrin N, Bartlett DL, etal. Peritoneal carcinomatosis

of rare ovarian origin treated by cytoreductive surgery and

hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy: a multi- institutional

cohort from PSOGI and BIG- RENAPE. Ann Surg Oncol

2018;25:1668–75.

55 Chua TC, Moran BJ, Sugarbaker PH, etal. Early- and long- term

outcome data of patients with pseudomyxoma peritonei from

appendiceal origin treated by a strategy of cytoreductive surgery

and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol

2012;30:2449–56.

56 Fu F, Ma X, Lu Y, etal. Clinicopathological characteristics and

prognostic prediction in pseudomyxoma peritonei originating from

mucinous ovarian cancer. Front Oncol 2021;11:641053.

57 Quénet F, Elias D, Roca L, etal. Cytoreductive surgery plus

hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy versus cytoreductive

surgery alone for colorectal peritoneal metastases (PRODIGE 7): a

multicentre, randomised, open- label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol

2021;22:256–66.

58 Tarumi Y, Mori T, Matsushima H, etal. Long- term survival with

bevacizumab in heavily pretreated and platinum- resistant

mucinous ovarian cancer: a case report. J Obstet Gynaecol Res

2018;44:347–51.

59 Winer I, Buckanovich RJ. A case of progressive mucinous ovarian

cancer of low malignant potential responsive to biologic therapy with

bevacizumab. Gynecol Oncol 2010;116:578–9.

60 Mueller JJ, Schlappe BA, Kumar R, etal. Massively parallel

sequencing analysis of mucinous ovarian carcinomas:

genomic profiling and differential diagnoses. Gynecol Oncol

2018;150:127–35.

61 Mackenzie R, Kommoss S, Winterhoff BJ, etal. Targeted deep

sequencing of mucinous ovarian tumors reveals multiple overlapping

RAS- pathway activating mutations in borderline and cancerous

neoplasms. BMC Cancer 2015;15:415.

62 Cheasley D, Wakeeld MJ, Ryland GL, etal. The molecular origin

and taxonomy of mucinous ovarian carcinoma. Nat Commun

2019;10:3935.

63 Anglesio MS, Kommoss S, Tolcher MC, etal. Molecular

characterization of mucinous ovarian tumours supports a stratied

treatment approach with HER2 targeting in 19% of carcinomas.

J Pathol 2013;229:111–20.

64 Ryland GL, Hunter SM, Doyle MA, etal. Mutational landscape of

mucinous ovarian carcinoma and its neoplastic precursors. Genome

Med 2015;7:87.

65 Chay W- Y, Chew S- H, Ong W- S, etal. HER2 amplication and

clinicopathological characteristics in a large Asian cohort of rare

mucinous ovarian cancer. PLoS One 2013;8:e61565.

66 McAlpine JN, Wiegand KC, Vang R, etal. HER2 overexpression and

amplication is present in a subset of ovarian mucinous carcinomas

and can be targeted with trastuzumab therapy. BMC Cancer

2009;9:433.

67 Gorringe KL, Cheasley D, Wakefield MJ, etal. Therapeutic

options for mucinous ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol

2020;156:552–60.

68 Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, etal. PD- 1 blockade in tumors with

mismatch- repair deficiency. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2509–20.

69 Marcus L, Lemery SJ, Keegan P, etal. FDA approval summary:

pembrolizumab for the treatment of microsatellite instability- high

solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25:3753–8.

70 Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic

analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature 2011;474:609–15.

71 Fader AN, Roque DM, Siegel E, etal. Randomized phase II trial of

carboplatin- paclitaxel versus carboplatin- paclitaxel- trastuzumab

in uterine serous carcinomas that overexpress human epidermal

growth factor receptor 2/neu. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:2044–51.

72 Javle M, Borad MJ, Azad NS, etal. Pertuzumab and trastuzumab

for HER2- positive, metastatic biliary tract cancer (MyPathway): a

multicentre, open- label, phase 2A, multiple basket study. Lancet

Oncol 2021;22:1290–300.

73 Swain SM, Miles D, Kim S- B, etal. Pertuzumab, trastuzumab,

and docetaxel for HER2- positive metastatic breast cancer

(CLEOPATRA): end- of- study results from a double- blind,

on August 30, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://ijgc.bmj.com/Int J Gynecol Cancer: first published as 10.1136/ijgc-2022-003806 on 13 October 2022. Downloaded from

1462

KurnitKC, FrumovitzM. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2022;32:1455–1462. doi:10.1136/ijgc-2022-003806

Review

randomised, placebo- controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol

2020;21:519–30.

74 Tkalia IG, Vorobyova LI, Svintsitsky VS, etal. Clinical signicance of

hormonal receptor status of malignant ovarian tumors. Exp Oncol

2014;36:125–33.

75 Jain A, Ryan PD, Seiden MV. Metastatic mucinous ovarian cancer

and treatment decisions based on histology and molecular

markers rather than the primary location. J Natl Compr Canc Netw

2012;10:1076–80.

76 Liu T, Hu W, Dalton HJ, etal. Targeting SRC and tubulin in mucinous

ovarian carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19:6532–43.

77 Matsuo K, Nishimura M, Bottsford- Miller JN, etal. Targeting SRC in

mucinous ovarian carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2011;17:5367–78.

78 Niiro E, Morioka S, Iwai K, etal. Potential signaling pathways as

therapeutic targets for overcoming chemoresistance in mucinous

ovarian cancer. Biomed Rep 2018;8:215–23.

79 Ricci F, Guffanti F, Affatato R, etal. Establishment of patient- derived

tumor xenograft models of mucinous ovarian cancer. Am J Cancer

Res 2020;10:572–80.

80 Hisamatsu T, McGuire M, Wu SY, etal. PRKRA/PACT expression

promotes chemoresistance of mucinous ovarian cancer. Mol Cancer

Ther 2019;18:162–72.

on August 30, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://ijgc.bmj.com/Int J Gynecol Cancer: first published as 10.1136/ijgc-2022-003806 on 13 October 2022. Downloaded from