A perfect mess:

Towards a typology of the “present perfect”

Margit Bowler & Sozen Ozkan

AIS • October 24, 2017

1 Introduction

1

• This talk is concerned with the meaning and use of cross-linguistic expressions that have been

described as “present perfects.”

• In English, we use the term “present perfect” to describe an expression with a present tense

auxiliary and a past tense main verb, as in (1).

• The English present perfect makes different pragmatic contributions, and has a different

distribution from, the English simple past in (2). The present perfect is typically described as

referring to a “past event of current relevance” (Comrie 1976).

(1) Usain Bolt has won the race. PRESENT PERFECT

(2) Usain Bolt won the race. SIMPLE PAST

• The term “present perfect” is used to refer to a number of different expressions across a range

of different languages.

– Languages that are assumed to have present perfects include (but are not limited to) En-

glish (McCawley 1981), Dutch (Pancheva and von Stechow 2004), Norwegian (Izvorski

1997), German (Musan 2001), Bulgarian (Izvorski 1997), Greek (Iatridou et al. 2001),

Kazakh (Straughn 2011), Turkish (S¸ener 2011), Tatar (Greed 2009), and Uzbek (Straughn

2011).

– Dahl (1985) gives a survey of present perfects across languages, although (as we argue

later) there are issues with his criteria for what qualifies as a present perfect.

• As we show in this talk, the distribution and use of the English present perfect is very different

from the so-called “present perfect” expressions in the other languages in our survey.

• This is a problem for linguists studying the present perfect cross-linguistically, since the vast

majority of semantic/pragmatic theories of the present perfect are based on the English data.

• In this talk, we show the distribution of the English present perfect, and test how its distri-

bution compares to so-called “present perfect” expressions in four other languages: Turkish

(Turkic), Tatar (Turkic), Bulgarian (Slavic), and German (Germanic).

1

We would like to thank Yael Sharvit, Roumi Pancheva, Rajesh Bhatt, Jessica Rett, and members of the UCLA

Semantics Tea and American Indian Seminar for their extremely generous and insightful feedback on this project. We

are very grateful also for our amazing language consultants: Maren Firpo (German), Sofia Mazgarova (Tatar), and

Vesela Simeonova (Bulgarian).

1

Towards a typology of the “present perfect” Bowler & Ozkan

2 What is the present perfect?: the view from English

• Conceptually speaking, the English present perfect is typically described as referring to a

“past event of current relevance” (Comrie 1976).

• There are a number of well-described distributional differences between the English present

perfect and simple past tense (Chomsky 1970, McCoard 1978, McCawley 1981, Klein 1992,

Katz 2003, among many others). We show these in §2.1, and use these as the basis for our

cross-linguistic questionnaire.

2.1 English present perfect data

• Present perfect puzzle (Klein 1992): Present perfect is ungrammatical with temporal ad-

juncts.

(3) a. * Usain Bolt has run yesterday.

b. Usain Bolt ran (yesterday).

• Current salience requirement (McCoard 1978): The described event must be salient at the

utterance time.

(4) a. ?? Gutenberg has discovered the art of printing.

b. Gutenberg discovered the art of printing.

• Perfect of result (Iatridou et al. 2001): Result state of present perfect expressions must be

true at the utterance time.

(5) a. Leroy has lost his keys (#but now he found them).

b. Leroy lost his keys (but now he found them).

• Lifetime effects (Chomsky 1970): Individuals in present perfect utterances must be alive at

the utterance time.

(6) a. ?? Einstein has visited Princeton.

b. Einstein visited Princeton.

• Universal perfect (McCawley 1981): When the present perfect occurs with a stative verb,

the state described by the verb must be true at the utterance time.

2

(7) Leroy has lived in Los Angeles since 2000 (#but he doesn’t live there anymore).

• Repeatability requirement (Katz 2003): Events described by a present perfect utterance

must be repeatable.

(8) Context: The Monet exhibit is closed; the addressee can no longer go to it.

a. # Have you been to the Monet exhibit?

b. Did you go to the Monet exhibit?

2

We use the term “universal perfect” from Iatridou et al. (2001); McCawley (1981) and Portner (2003), among

others, refer to these as continuative perfects.

2

Towards a typology of the “present perfect” Bowler & Ozkan

• Present perfect in questions:

– Questions about specific past times: The present perfect is infelicitous in questions

about specific past times, unlike the simple past.

(9) Context: Our mutual friend Leroy is a somewhat picky eater. I know that Leroy

went to a Japanese restaurant last night, and that you talked to him after he

went there. I ask you:

a. Did Leroy eat sushi?

b. # Has Leroy eaten sushi?

– Questions about the general past: The present perfect is felicitous in questions about

general past events, unlike the simple past.

(10) Context: You are discussing foods you have tried with your co-workers. Your

co-worker Leroy is notoriously picky. You ask your mutual friend Howard:

a. Has Leroy eaten sushi?

b. # Did Leroy eat sushi?

– Out of the blue questions: Present perfect is felicitous in out of the blue questions,

unlike the simple past.

(11) Context: Leroy pokes his head in his co-worker’s office and asks:

a. Have you eaten sushi?

b. # Did you eat sushi?

2.2 Brief review of theories of the (English) present perfect

• Theories of the present perfect attempt to account for some or all of the data in §2.1, and

differ in what they assume is the most important data to account for.

– “Extended now” (XN) theories (McCoard 1978, Dowty 1979, Bhatt and Pancheva

2005, Iatridou et al. 2001, among others):

∗ Take the salience data in (4a) as a core property of the meaning of the present

perfect.

∗ Propose to treat the present perfect as extending the speaker’s “now” to include

times in the past as well as the utterance time.

∗ We give a basic XN denotation for the perfect in (12):

(12) JPERFECTK = λp

<i,t>

λt

<i>

. ∃t

0

<i>

[XN(t

0

,t) & p(t

0

)]

(where XN(t

0

,t) iff t is a final subinterval of t

0

)

(Bhatt and Pancheva 2005, 7, following Dowty 1979)

∗ In (12), the perfect combines with an untensed proposition, p. The perfect intro-

duces an interval that extends back from, and includes, the reference time t, and

asserts that p is true in that interval. In this way, the speaker’s reference time (their

“now”) is extended into the past.

3

Towards a typology of the “present perfect” Bowler & Ozkan

– “Definite times” constraint (Klein 1992):

∗ Takes the present perfect puzzle, i.e., the inability of the present perfect to co-occur

with (most) past temporal adjuncts (3a) to be its most noteworthy property. (This

is a primarily syntactic diagnosis of the present perfect.)

∗ Roughly speaking, proposes a pragmatic constraint stating that an expression cannot

have a topic time and event time that are both picked out as “definite times” relative

to the utterance time.

(13) * John has left at six.

Topic time = at six (definite)

Event time = time picked out by has left; definite under Klein’s theory

– Modal theory (Katz 2003):

∗ Takes the repeatability data in (8a) as the core property of the present perfect, and

argues that it motivates including a modal component in the semantics.

(14) JPRES.PERFK

c

= λp: ∃t [t

c

<t & POSS(p,t,c)]. ∃e [τ (e) < t

c

& p(e)(w

c

)]

(where τ (e) picks out the run time of the event)

(Katz 2003, 154)

∗ Roughly speaking, argues that present perfect expressions presuppose that it is pos-

sible for an event of the type denoted by the expression to occur in the future, and

assert that one has occurred in the past.

3 Cross-linguistic comparison

• A number of authors have noted that the syntactic and pragmatic properties of the English

present perfect in §2.1 do not occur in present perfects across all languages (Plungian 2011,

Dahl 2000, Dahl 1985, among others).

– Nonetheless, Dahl (1985) uses the distribution of the English present perfect in §2.1 as

a diagnosis for the present perfect cross-linguistically.

• In the following sections, we compare the uses of the so-called “present perfect” in Turkish,

Tatar, Bulgarian, and German to the English data in §2.1.

• For space reasons, we only show expressions that have been previously argued to express the

present perfect. We do not compare these with the simple past.

• We show that these languages pattern very differently from English. We summarize our

findings in §4.

– Side note: Turkish, Tatar, and Bulgarian have all been described as having “perfect of

evidentiality” (PE) (Izvorski 1997, S¸ener 2011).

∗ In PE languages, “perfect” morphology also conveys that the speaker has indirect

evidence for the embedded proposition.

∗ To control for this, we give contexts in which the speaker has indirect evidence for

the Turkish (§3.1), Tatar (§3.2), and Bulgarian (§3.3) expressions.

4

Towards a typology of the “present perfect” Bowler & Ozkan

3.1 Comparison of Turkish and English

Turkish “present perfect”: The Turkish verbal suffix -mIs¸ is proposed to mark both indirect

evidentiality and present perfect (Izvorski 1997, S¸ener 2011).

a

a

Following Turkicist tradition, we capitalize letters to indicate underspecified segments that are subject to

vowel harmony or voice/place/manner assimilation.

• Present perfect puzzle: The present perfect puzzle does not apply to Turkish expressions

with -mIs¸; d

¨

un ‘yesterday’ is grammatical in (15), contrary to the English example in (3a).

(15) Present perfect puzzle context: The speaker walks into the Olympic changing room the

morning after a race and sees Usain Bolt’s jersey in the laundry basket. She didn’t witness

the race, but has evidence that Usain Bolt ran yesterday. She says:

Usain

Usain

Bolt

Bolt

d

¨

un

yesterday

kos¸-mus¸-∅.

run-MIS-3SG

‘[I have indirect evidence that] Usain Bolt ran yesterday.’

• Current salience requirement: Turkish expressions with -mIs¸ do not require that the event

described by the verb be salient at the utterance time, unlike English (4a).

(16) Current salience context: You have been studying the history of art of printing. You see

Gutenberg’s name everywhere in the resources and you make the inference that Gutenberg

discovered the art of printing. You say:

Gutenberg

Gutenberg

basım

printing

sanat-ın-ı

art-3S-ACC

kes¸fet-mis¸-∅.

discover-MIS-3SG

‘[I have indirect evidence that] Gutenberg discovered the art of printing.’

• Perfect of result: The result state of perfect of result expressions do not need to be true at

the utterance time in Turkish, unlike in English (5a).

(17) Perfect of result context: Your roommate Ali calls you and tells you that he has been

rummaging through his pockets and he can’t find his keys. You tell him you haven’t seen

them either. He calls you back later to tell you that he found them. Your officemate asks

you what happened. You say:

Ali

Ali

anahtar-lar-ın-ı

key-PL-3SG-ACC

kaybet-mis¸-∅

lose-MIS-3SG

(ama

but

s¸imdi

now

bul-mus

"

-∅).

find-MIS-3SG

‘[I have indirect evidence that] Ali lost his keys (but now he found them).’

• Lifetime effects: Contrary to the lifetime effects observed in English (6a), the individuals in

Turkish expressions with -mIs¸ do not need to be alive, as in (18).

5

Towards a typology of the “present perfect” Bowler & Ozkan

(18) Lifetime effects context: You visit Princeton and see Einstein’s signature in the physics

department guestbook. You say:

Einstein

Einstein

Princeton-ı

Princeton-ACC

ziyaret

visit

et-mis¸-∅.

do-MIS-3SG

‘[I have indirect evidence that] Einstein visited Princeton.’

• Universal perfect: The state described by the verb in a Turkish “universal perfect” must be

false at the utterance time, unlike in English (7). It is infelicitous to report (19) if Ali still

lives in Istanbul at the utterance time, as shown by (19b).

(19) Universal perfect context: You have not heard from your friend Ali in a long time. You go

on his Facebook page and see that he moved to Istanbul in 2010. Then, you see a newer

post saying that he accepted a job in Ankara. You say:

Ali

Ali

2010-dan

2010-ABL

beri

since

Istanbul-da

Istanbul-LOC

yas¸a-mıs¸-∅.

live-MIS-3SG

a. X‘[I have indirect evidence that] Ali has lived in Istanbul since 2010 [but he doesn’t

live there anymore].’

b. #‘[I have indirect evidence that] Ali has lived in Istanbul since 2010 [and he still lives

there today].’

• Repeatability requirement: Unlike the repeatability effects observed in English (8a), the

event described by a Turkish expression including -mIs¸ does not need to be repeatable.

(20) Repeatability context: You are discussing the Picasso exhibit at LACMA with your friend

Ays¸e. You are curious if your mutual friend Leyla went to see it. The Picasso exhibit is

closed now; Leyla can no longer go to it. You ask:

3

Leyla

Leyla

Picasso

Picasso

sergi-sin-e

exhibit-3SG-DAT

git-mis¸-∅

go-MIS-3SG

mi?

Q

‘Did Leyla go to the Picasso exhibit?’

• Questions about specific past times: Unlike in English (9), -mIs¸ is felicitous in questions

about specific past times, as in (21).

(21) Question about a specific past time: Seren is a somewhat picky eater. I know that Seren

went to a Japanese restaurant last night, and that you talked to her after she went there. I

ask you:

Seren

Seren

sus¸i

sushi

ye-mis¸-∅

eat-MIS-3SG

mi?

Q

‘Did Seren eat sushi?’

3

In Turkish questions, the choice of evidential (-DI or -mIs¸) reflects the evidence that the speaker assumes the

addressee has for the relevant proposition. This is termed interrogative flip (San Roque et al. 2015). (20) therefore

requires that the speaker ask a question about a third party, rather than about the addressee, since the addressee

presumably has direct evidence for their own actions (and therefore could not use -mIs¸). The same is true for (23).

6

Towards a typology of the “present perfect” Bowler & Ozkan

• Questions about the general past & out of the blue questions: Out of the blue questions

and questions about the general past both generally require the inclusion of hic¸ ‘ever’ to make

the expression felicitous. Without hic¸, the interpretation is that the speaker is referring to a

specific time, as in (21).

4

(22) Question about the general past: You are discussing food preferences with your co-

workers. Your co- worker Ays¸e is notoriously picky. You ask your mutual friend Leyla:

Ays¸e

Ali

hic¸

ever

sus¸i

sushi

ye-mis¸-∅

eat-MIS-3SG

mi?

Q

‘Has Ays¸e ever eaten sushi?’

(23) Out of the blue question context: Your co-worker sticks their head in your office and

asks:

Ali

Ali

hic¸

ever

sus¸i

sushi

ye-mis¸-∅

eat-MIS-3SG

mi?

Q

‘Has Ali ever eaten sushi?’

3.1.1 Recap: Turkish -mIs¸ expressions

• None of the distributional diagnostics from the English data in §2.1 are observed in Turkish

-mIs¸ expressions. Turkish -mIs¸ expressions do not show any English-type present perfect

behavior.

• In universal perfect expressions like (19), -mIs¸ patterns oppositely from the English present

perfect: the proposition must be false at the utterance time.

• This contrasts with the behavior of -mIs¸ in perfect of result expressions like (17), in which

the proposition is optionally false at the utterance time. At present, we have no explanation

as to why this is the case.

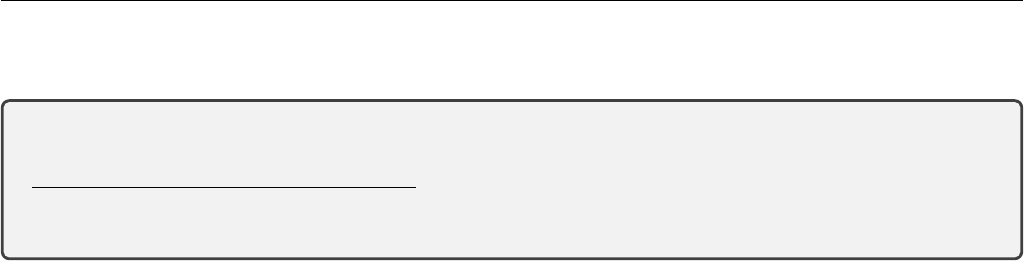

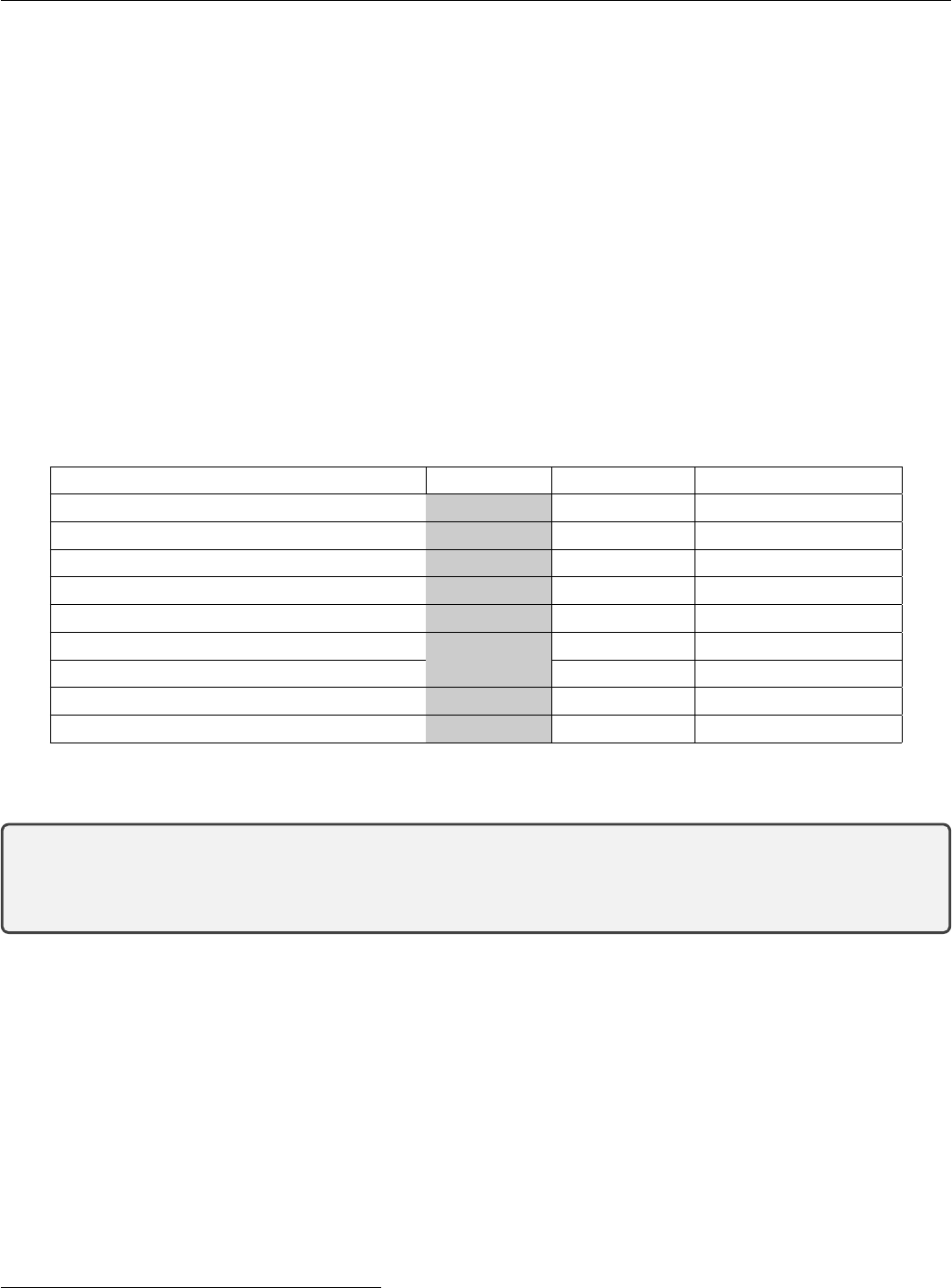

Eng (PPF) Eng (SP) Turkish -mIs¸

OK with past temporal adverbs no yes yes

Event must be salient at UT yes no no

Result must be true at UT yes no no

Lifetime effects apply yes no no

Universal perfect must be true at UT yes n/a no (must not)

Event must be repeatable yes no no

OK in questions about specific past no yes yes

OK in questions about general past yes only w/ adv. only w/ adv.

OK in out of the blue questions yes only w/ adv. only w/ adv.

4

We observe that English simple past tense utterances like (11b) are also improved in out of the blue questions with

the inclusion of ever: Did you ever eat sushi? is better as an out of the blue question than Did you eat sushi?

7

Towards a typology of the “present perfect” Bowler & Ozkan

3.2 Comparison of Tatar and English

Tatar “present perfect”: The Tatar verbal suffix -GAn is proposed to mark both indirect

evidentiality and present perfect (Greed 2009, Tatevosov 2007).

• Present perfect puzzle: The present perfect puzzle does not apply to Tatar expressions with

-GAn; kic¸

¨

a ‘yesterday’ is grammatical in (24), contrary to the English example in (3a).

(24) Present perfect puzzle context: The speaker walks into an Olympic changing room the

morning after a race and sees Usain Bolt’s jersey in the laundry basket. She didn’t witness

the race, but has evidence that Usain Bolt ran yesterday. She says:

Usain

Usain

Bolt

Bolt

kic¸

¨

a

yesterday

yeger-g

¨

an.

run-GAN

‘[I have indirect evidence that] Usain Bolt ran yesterday.’

• Current salience requirement: Tatar expressions with -GAn do not require that the event

described by the verb be salient at the utterance time, unlike English (4a).

(25) Current salience context: You have been studying the history of art of printing. You see

Gutenberg’s name everywhere in the resources and you make the inference that Gutenberg

invented the art of printing. You say:

Gutenberg

Gutenberg

n

¨

as¸riy

¨

at

print

s

¨

an

˘

g

¨

at-e-n

art-3SG.POSS-ACC

uyl-ap

think-YP

c¸ı

˘

gar-

˘

gan.

invent-GAN

‘[I have indirect evidence that] Gutenberg invented the art of printing.’

• Perfect of result: The result state of perfect of result expressions do not need to be true at

the utterance time in Tatar, unlike in English (5a).

(26) Perfect of result context: Your husband Ali calls you and tells you that he can’t find his

keys. Later, he calls you back and says he found his keys. Your officemate asks what

happened. You say:

Ali

Ali

ac¸qıc¸-ın

key-ACC

yu

˘

galt-qan

lose-GAN

(l

¨

akin

but

beraz-dan

short.time-ABL

so

˜

n

after

tap-qan).

find-GAN

‘[I have indirect evidence that] Ali lost his keys (but after a little while he found them).’

• Lifetime effects: Contrary to the lifetime effects observed in English (6a), the individuals in

Tatar expressions with -GAn do not need to be alive at the utterance time, as in (27).

(27) Lifetime effects context: You visit Princeton and see Einstein’s signature in the physics

department guestbook. You say:

Ens¸tein

Einstein

Prinston-

˘

ga

Princeton-DAT

bar-

˘

gan.

go-GAN

‘[I have indirect evidence that] Einstein went to Princeton.’

• Universal perfect: Tatar patterns like Turkish, and unlike English, in that the state described

by a Tatar “universal perfect” must be false at the utterance time. It is infelicitous to report

(28) if Guzel still lives in Istanbul at the utterance time, as shown in (28b).

8

Towards a typology of the “present perfect” Bowler & Ozkan

(28) Universal perfect context: You have not heard from your friend Guzel in a long time. You

go on her Facebook page and see that he moved to Los Angeles in 2010. Then, you see a

newer post saying that she accepted a job in Kazan. You say:

G

¨

uz

¨

al

Guzel

Los

Los

Angeles-ta

Angeles-LOC

ike

two

men

thousand

un

¨

oc¸enc¸e

thirteenth

yel-dan

year-ABL

birle

since

y

¨

as¸

¨

a-g

¨

an.

live-GAN

a. X ‘[I have indirect evidence that] Guzel lived in Los Angeles since 2010 [but she

doesn’t live there anymore].’

b. # ‘[I have indirect evidence that] Guzel lived in Los Angeles since 2010 [and she still

lives there today].’

• Repeatability requirement: Unlike the repeatability effects observed in English (8a), the

event described by a Tatar expression including -GAn does not need to be repeatable, as in

(29).

(29) Repeatability context: You are discussing the Monet exhibit at LACMA. You are curious

if our mutual friend Travis went to see it. The Monet exhibit is closed now; Travis can no

longer go to it. You ask:

Travis

Travis

Monet

Monet

k

¨

urg

¨

azm

¨

a-se-n

¨

a

exhibit-3SG.POSS-DAT

bar-

˘

gan

go-GAN

mı?

Q

‘Did Travis go to the Monet exhibit?’

• Questions about specific past times: Unlike the English present perfect in (9), Tatar -GAn

is felicitous in questions about specific past times, as in (30).

(30) Question about a specific past time: Aigel is a somewhat picky eater. I know that she

went to a Japanese restaurant last night, and that you talked to her after she went there. I

ask you:

Ayg

¨

ol

Aigel

sus¸i

sushi

as¸a-

˘

gan

eat-GAN

mı?

Q

‘Did Aigel eat sushi?’

• Questions about the general past & out of the blue questions: Tatar expressions with

-GAn, like (plain) Turkish expressions with -mIs¸, cannot occur in questions about the general

past and out of the blue questions.

• Instead, Tatar speakers must use an expression containing a nominalized form of the verb

and the existential bar ‘EXIST.’

5

We show examples of this expression in (32b) and (33b).

5

This expression seems to pattern pragmatically more like the English present perfect data in §2.1. For instance,

like the English data in (8a), the event described by a Tatar expression including bar + a verbal nominalization needs

to be repeatable.

(31) Repeatability context: You are discussing the Monet exhibit at LACMA. You are curious if our mutual friend

Travis went to see it. The Monet exhibit is closed now; Travis can no longer go to it. You ask:

#Travis-nın

Travis-GEN

Monet

Monet

k

¨

urg

¨

azm

¨

a-se-n

¨

a

exhibit-3SG.POSS-DAT

bar-

˘

gan-ı

go-PST.INDEF-ACC

bar

EXIST

mı?

Q?

‘Has Travis been to the Monet exhibit?’

9

Towards a typology of the “present perfect” Bowler & Ozkan

(32) Question about the general past: You are discussing food preferences with your co-

workers. Your co-worker Aigel is notoriously picky. You ask your mutual friend Leyla:

a. # Ayg

¨

ol

Aigel

sus¸i

sushi

as¸a-

˘

gan

eat-GAN

mı?

Q

‘Did Aigel eat sushi?’

b. X Ayg

¨

ol-nen

Aigel-GEN

sus¸i

sus¸i

as¸a-

˘

gan-ı

eat-GAN-3SG.POSS

bar

EXIST

mı?

Q

‘Has Aigel ever eaten sushi?’

Literally: ‘Does Aigel’s eating sushi exist?’

(33) Out of the blue question: Your co-worker sticks their head in your office and asks:

a. # Ayg

¨

ol

Aigel

sushi

sushi

as¸a-

˘

gan

eat-GAN

mı?

Q

‘Did Aigel eat sushi?’

b. X Ayg

¨

ol-nen

Aigel-GEN

sus¸i

sushi

as¸a-

˘

gan-ı

eat-GAN-3SG.POSS

bar

EXIST

mı?

Q

‘Has Aigel ever eaten sushi?’

Literally: ‘Does Aigel’s eating sushi exist?’

3.2.1 Recap: Tatar -GAn expressions

• Tatar -GAn patterns very similar to Turkish -mIs¸ with respect to our questionnaire.

• Tatar diverges from only Turkish with respect to out of the blue questions and questions

about the general past. Tatar speakers must use a verbal nominalization + bar ‘EXIST’ in

these contexts.

• None of the distributional diagnostics from the English data in §2.1 are observed in Tatar

-GAn expressions. We find no evidence supporting a proposal to treat Tatar -GAn expressions

as encoding English-type present perfect.

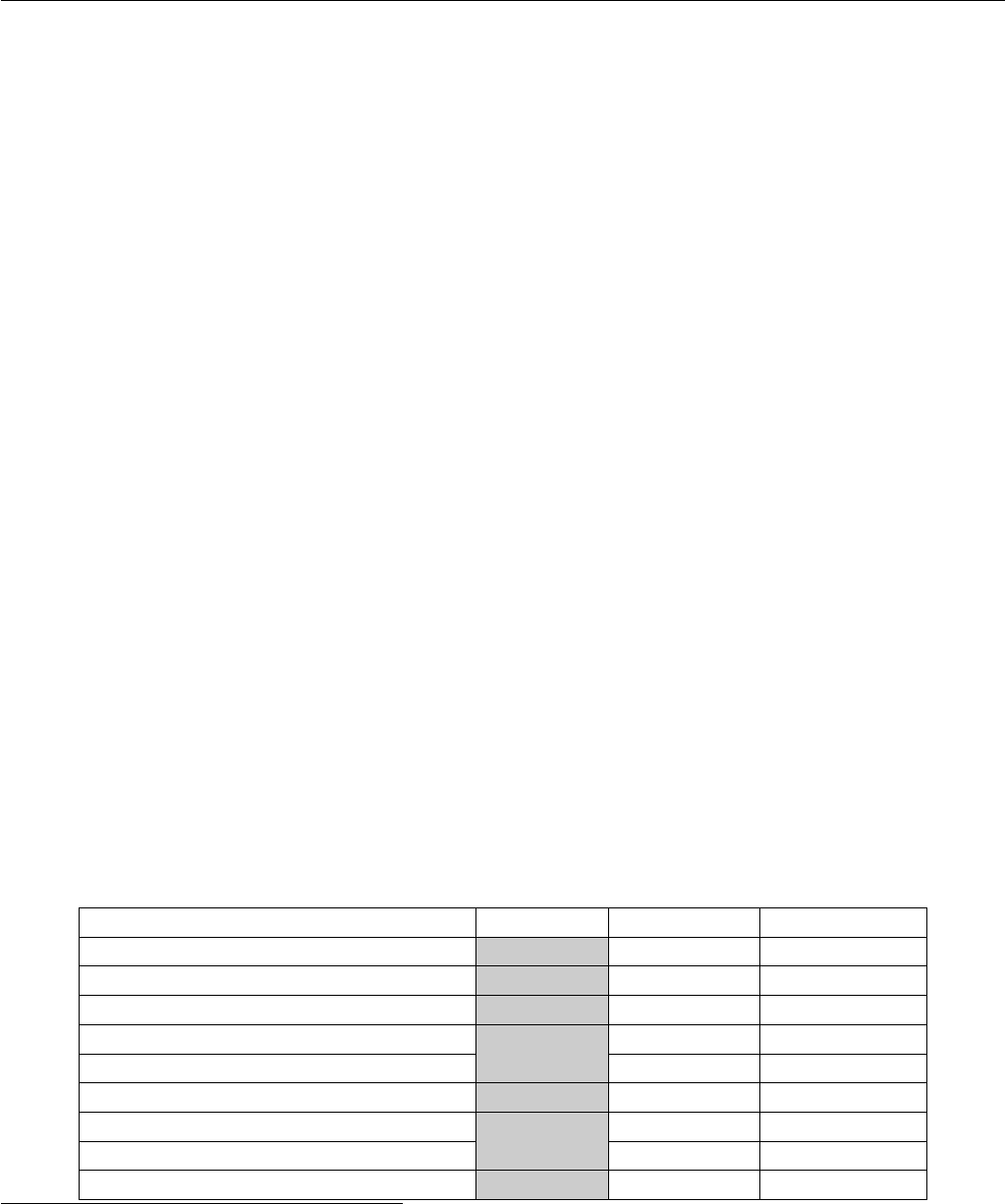

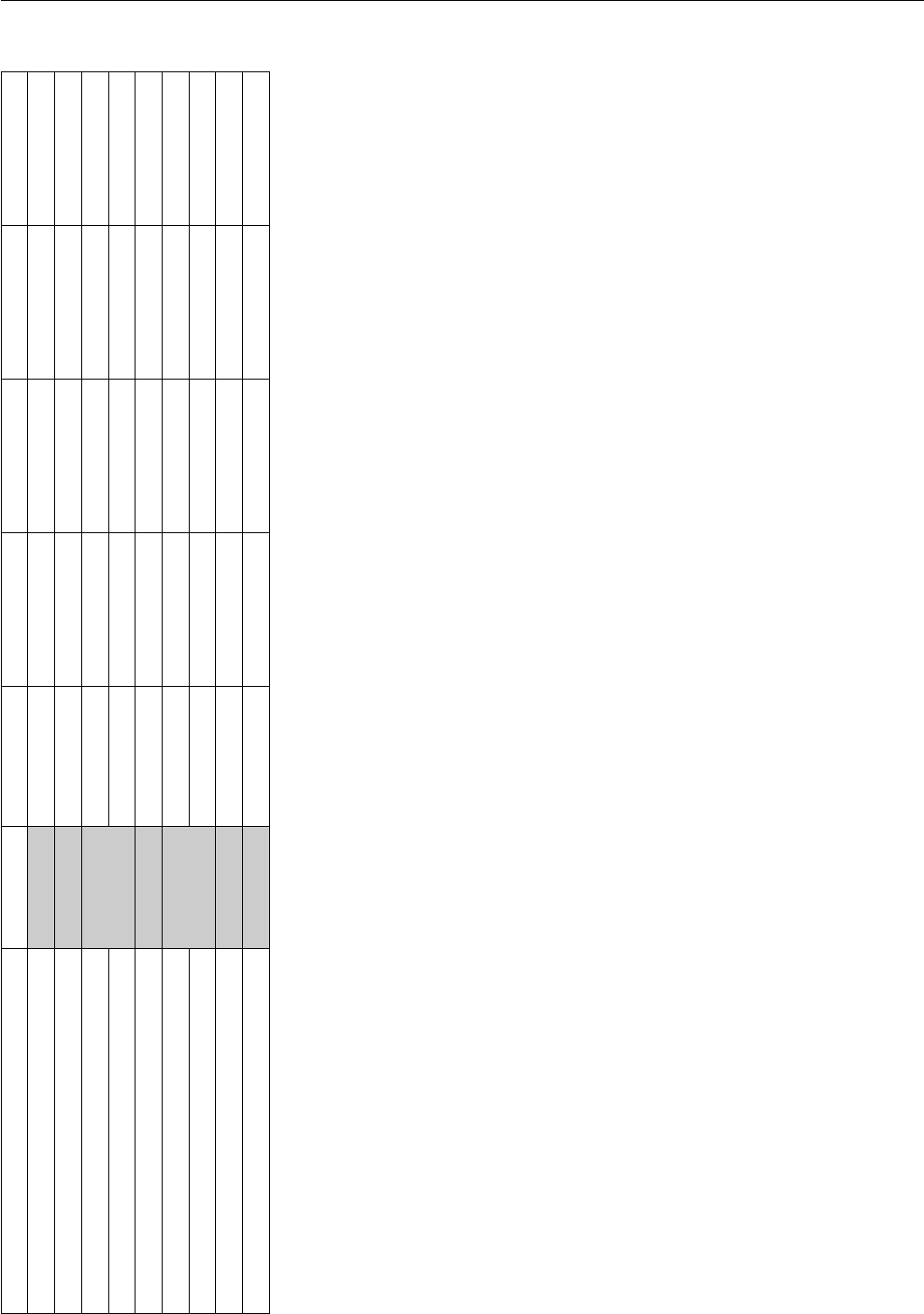

Eng (PPF) Eng (SP) Tatar -GAn

OK with past temporal adverbs no yes yes

Event must be salient at UT yes no no

Result must be true at UT yes no no

Lifetime effects apply yes no no

Universal perfect must be true at UT yes n/a no (must not)

Event must be repeatable yes no no

OK in questions about specific past no yes yes

OK in questions about general past yes only w/ adv. only w/ EXIST

OK in out of the blue questions yes only w/ adv. only w/ EXIST

10

Towards a typology of the “present perfect” Bowler & Ozkan

3.3 Comparison of Bulgarian and English

Bulgarian “present perfect”: In Bulgarian, present perfect is assumed to be contributed by

a combination of a present tense auxiliary and main verb past participal (Izvorski 1997). We

will refer to this construction as be + PP.

• Present perfect puzzle: The present perfect puzzle does not apply to Bulgarian be + PP

expressions; vchera ‘yesterday’ is grammatical in (34), contrary to the English example in

(3a).

(34) Present perfect puzzle context: The speaker walks into an Olympic changing room the

morning after a race and sees Usain Bolt’s jersey in the laundry basket. She didn’t witness

the race, but has evidence that Usain Bolt ran yesterday. She says:

Usain

Usain

Bolt

Bolt

e

be.PRES.3SG

byagal

run.PP.MASC.SG

vchera.

yesterday

‘[I have indirect evidence that] Usain Bolt ran yesterday.’

• Current salience requirement: Bulgarian be + PP expressions do not require that the event

described by the verb be salient at the utterance time, unlike English (4a).

(35) Current salience context: You have been studying the history of art of printing. You see

Gutenberg’s name everywhere in the resources and you make the inference that Gutenberg

invented the art of printing. You say:

Gutenberg

Gutenberg

e

be.PRES.3SG

izobretil

invent.PP.MASC.SG

pechatnata

printing.DEF.FEM.SG

presa.

press.FEM.SG

‘[I have indirect evidence that] Gutenberg invented the printing press.’

• Perfect of result: The result state of perfect of result expressions needs to be true at the

utterance time in Bulgarian be + PP expressions, similar to English (5a).

(36) Perfect of result context: Your husband Ali calls you and tells you that he can’t find his

keys. Later, he calls you back and says he found his keys. Your officemate asks what

happened. You say:

Ali

Ali

si

REFL.POSS

e

be.PRES.3SG

zagubil

lose.PP.MASC.SG

klyuchovete,

key.DEF.PL

(#no

but

sega

now

gi

3PL.ACC

e

be.PRES.3SG

nameril).

find.PP.MASC.SG

‘[I have indirect evidence that] Ali lost his keys (#but now he found them).’

• Lifetime effects: Contrary to the lifetime effects observed in English (6a), the individuals in

Bulgarian be + PP expressions do not need to be alive at the utterance time, as in (37).

(37) Lifetime effects context: You visit Princeton and see Einstein’s signature in the physics

department guestbook. You say:

Einstein

Einstein

e

be.PRES.3SG

posetil

visit.PP.MASC.SG

Princeton.

Princeton

‘[I have indirect evidence that] Einstein visited Princeton.’

11

Towards a typology of the “present perfect” Bowler & Ozkan

• Universal perfect: The state described by the verb must be false at the utterance time in

Bulgarian.

(38) Universal perfect context: You have not heard from your friend Ali in a long time. You go

on his Facebook page and see that he moved to Istanbul in 2010. Then, you see a newer

post saying that he accepted a job in Ankara. You say:

Ali

Ali

e

be.PRES.3SG

zhivyal

live.PP.3SG.MASC

v

LOC

Istanbul

Istanbul

ot

from

2010

2010

(no

but

veche

already

ne

not

zhivee

live.PRES.3SG

tam).

there

‘[I have indirect evidence that] Ali lived in Istanbul since 2010 (but he doesn’t live there

any more).’

• Repeatability effects: Unlike the repeatability effects observed in English (8a), the event

described by a Bulgarian be + PP expression does not need to be repeatable.

(39) Repeatability context: You are discussing the Picasso exhibit at LACMA. You are curious

if our mutual friend Leyla went to see it. The Picasso exhibit is closed now; Leyla can no

longer go to it. You ask:

Leyla

Leyla

otishla

go.PP.FEM.SG

li

Q

e

be.PRES.3SG

na

at

izlozhbata

exhibition.DEF

na

at

Picasso?

Picasso

‘Did Leyla go to the Picasso exhibit?’

• Questions about specific past times: Like the English present perfect, Bulgarian be + PP

expressions are infelicitous if the speaker is asking about a specific past time.

(40) Question about specific past time: Our mutual friend Seren is a somewhat picky eater. I

know that Seren went to a Japanese restaurant last night, and that you talked to her after

she went there. I ask you:

a. X Seren

Seren

yade

eat.PST.3SG

li

Q

sushi?

sushi

‘Did Seren eat sushi?’

b. # Seren

Seren

yala

eat.PP.FEM.SG

li

Q

e

be.PRES.3SG

sushi?

sushi

• Questions about the general past & out of the blue questions: Like English, and unlike

Turkish and Tatar, Bulgarian be + PP expressions are felicitous in questions about the general

past and in out of the blue questions.

(41) Question about the general past: You are discussing food preferences with your co-

workers. Your co-worker Ayse is notoriously picky. You ask your mutual friend Leyla:

Ayse

Ayse

yala

eat.PP.FEM.SG

li

Q

e

be.PRES.3SG

(nyakoga)

ever

sushi?

sushi

‘Has Ayse (ever) eaten sushi?’

(42) Out of the blue question: Your co-worker sticks their head in your office and asks out of

the blue:

Ali

Ali

yal

eat.PP.MASC.SG

li

Q

e

be.PRES.3SG

sushi?

sushi

‘Has Ali eaten sushi?’

12

Towards a typology of the “present perfect” Bowler & Ozkan

3.3.1 Recap: Bulgarian be + PP expressions

• Bulgarian be + PP expressions pattern similarly to Turkish -mIs¸ and Tatar -GAn expressions,

with the exception of their use in perfect of result and in questions.

– Similar to English, the result state of perfect of result expressions must be true in Bul-

garian.

– Bulgarian is similar to English in that be + PP expressions are felicitous in out of the blue

questions and questions about the general past.

– The availability of be + PP in out of the blue questions and questions about the general

past differentiates Bulgarian from Turkish and Tatar.

• The majority of the distributional diagnostics from the English data in §2.1 are not observed

in Bulgarian be + PP expressions. The evidence supporting a proposal to treat Bulgarian be

+ PP expressions as encoding English-type present perfect is weak.

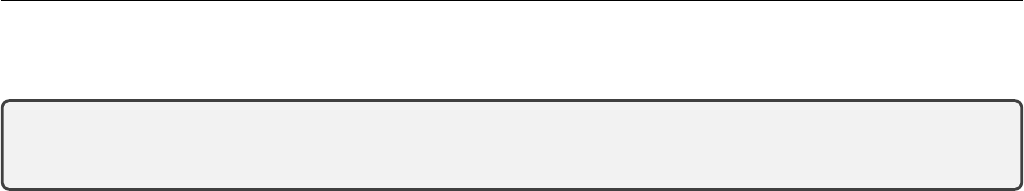

Eng (PPF) Eng (SP) Bulgarian be + PP

OK with past temporal adverbs no yes yes

Event must be salient at UT yes no no

Result must be true at UT yes no yes

Lifetime effects apply yes no no

Universal perfect must be true at UT yes n/a no (must not)

Event must be repeatable yes no no

OK in questions about specific past no yes no

OK in questions about general past yes only w/ adv. yes

OK in out of the blue questions yes only w/ adv. yes

3.4 Comparison of German and English

German “present perfect”: In German, the present perfect is assumed to be contributed by

a combination of a present tense auxiliary and main verb past participal (Pancheva and von

Stechow 2004, Musan 2001). We will refer to this construction as have + PP.

• Present perfect puzzle: The present perfect puzzle does not apply in German; gestern ‘yes-

terday’ is grammatical in (43), contrary to the English example in (3a).

(43) Present perfect puzzle context: You watched the Olympics yesterday and saw Usain Bolt

run a race. Today you’re discussing the race that you saw yesterday.

6

Usain

Usain

Bolt

Bolt

ist

is

gestern

yesterday

gelaufen.

run.PP

‘Usain Bolt ran yesterday.’

• Current salience requirement: German have + PP expressions do not require that the event

described by the verb be salient at the utterance time, unlike English (4a).

6

In German expressions involving verbs of motion, the auxiliary is sein ‘to be’ rather than haben ‘to have.’

13

Towards a typology of the “present perfect” Bowler & Ozkan

(44) Current salience context: You have been studying the history of art of printing. You see

Gutenberg’s name everywhere in the resources and you make the inference that Gutenberg

discovered the art of printing. You say:

Gutenberg

Gutenberg

hat

has

die

the

Kunst

art

des

of.the

Druckens

printing

erfunden.

discover.PP

‘Gutenburg discovered the art of printing.’

• Perfect of result: The result state of perfect of result expressions do not need to be true at

the utterance time in German have + PP expressions, unlike in English (5a).

(45) Perfect of result context: Your husband Ryan tells you that he can’t find his keys. You

haven’t seen them either. Later, however, then, he checks a coat pocket he hadn’t looked in

before and finds them.

Ryan

Ryan

hat

has

seine

his

Schl

¨

ussel

keys

verloren

lost.PP

(aber

but

jetzt

now

hat

has

er

he

sie

them

gefunden).

find.PP

‘Ryan lost his keys (but now he found them).’

• Lifetime effects: Contrary to the lifetime effects observed in English (6a), the individuals in

German have + PP expressions do not need to be alive at the utterance time, as in (46).

(46) Lifetime effects context: You visit Princeton and see Einstein’s signature in the physics

department guestbook. You say:

Einstein

Einstein

hat

has

Princeton

Princeton

besucht.

visit.PP

‘Einstein visited Princeton.’

• Universal perfect: Like Turkish, Tatar, and Bulgarian, and unlike English, the state described

by a German “universal perfect” should be false at the utterance time. It is infelicitous to

report (48) if Sarah still lives in Los Angeles at the utterance time, as shown in (47).

7

(48) Universal perfect context: You are telling someone about your friend Sarah, who moved

to Los Angeles in 2012.

Sarah

Sarah

hat

has

seit

since

zwei

two

tausend

thousand

zw

¨

olf

twelve

in

in

Los

Los

Angeles

Angeles

gelebt.

live.PP

a. X ‘Sarah lived in Los Angeles since 2012 [and she doesn’t live there anymore].’

b. # ‘Sarah lived in Los Angeles since 2012 [and she still lives there today].’

• Repeatability requirement: Unlike the repeatability effects observed in English (8a), the

event described by a German have + PP expression does not need to be repeatable, as in

(49).

7

To express that Sarah still lives in LA at the utterance time, German speakers must use a present tense verb:

(47) Sarah

Sarah

lebt

live.PRES

seit

since

zwei

two

tausend

thousand

zw

¨

olf

twelve

in

in

Los

Los

Angeles.

Angeles

‘Sarah lives in Los Angeles since 2012 [and she still lives there today].’

14

Towards a typology of the “present perfect” Bowler & Ozkan

(49) Repeatability context: You are discussing the Picasso exhibit at LACMA with your friend

John. You are curious if he went to see it. The Picasso exhibit is closed now; he can no

longer go to it. You ask:

Hast

have

du

you

die

the

Picasso

Picasso

Austellung

exhibit

gesehen?

see.PP

‘Did you see the Picasso exhibit?’

• Questions about specific past times: Unlike the English present perfect (9), German have

+ PP expressions are felicitous in questions about specific past times, as in (50).

(50) Question about specific past time: Our mutual friend John is a somewhat picky eater. I

know that you and John went to a Japanese restaurant last night. I ask you:

Hat

have.3SG

John

John

sushi

sushi

gegessen?

eat.PP

‘Did John eat sushi?’

• Questions about the general past & out of the blue questions: Similar to Turkish (22)

and (23) and unlike English (10a) and (11a), questions about the general past and out of the

blue questions in German also require the inclusion of an adverb. The expressions in (51) &

(52) are only felicitous in the given contexts with schon mal ‘already’.

(51) Question about the general past: You are discussing food preferences with your co-

workers. Your co-worker Sarah is notoriously picky. You ask your mutual friend John:

Hat

have.3SG

Sarah

Sarah

schon

already

mal

one.time

sushi

sushi

gegessen?

eat.PP

‘Has Sarah already eaten sushi?’

(52) Out of the blue question: Your co-worker sticks their head in your office and asks out of

the blue:

Hat

have.3SG

Sarah

Sarah

schon

already

mal

one.time

sushi

sushi

gegessen?

eat.PP

‘Has Sarah already eaten sushi?’

3.4.1 Recap: German have + PP expressions

• German have + PP expressions pattern identically to Turkish -mIs¸ expressions.

• None of the distributional diagnostics from the English data in §2.1 are observed in German

have + PP expressions. We find no evidence supporting a proposal to treat German have +

PP expressions as encoding English-type present perfect.

• However, German patterns overall quite differently from English in that the German simple

past tense is typically used only in written speech or in very formal contexts. German have +

PP expressions are the primary strategy used to talk about past times.

15

Towards a typology of the “present perfect” Bowler & Ozkan

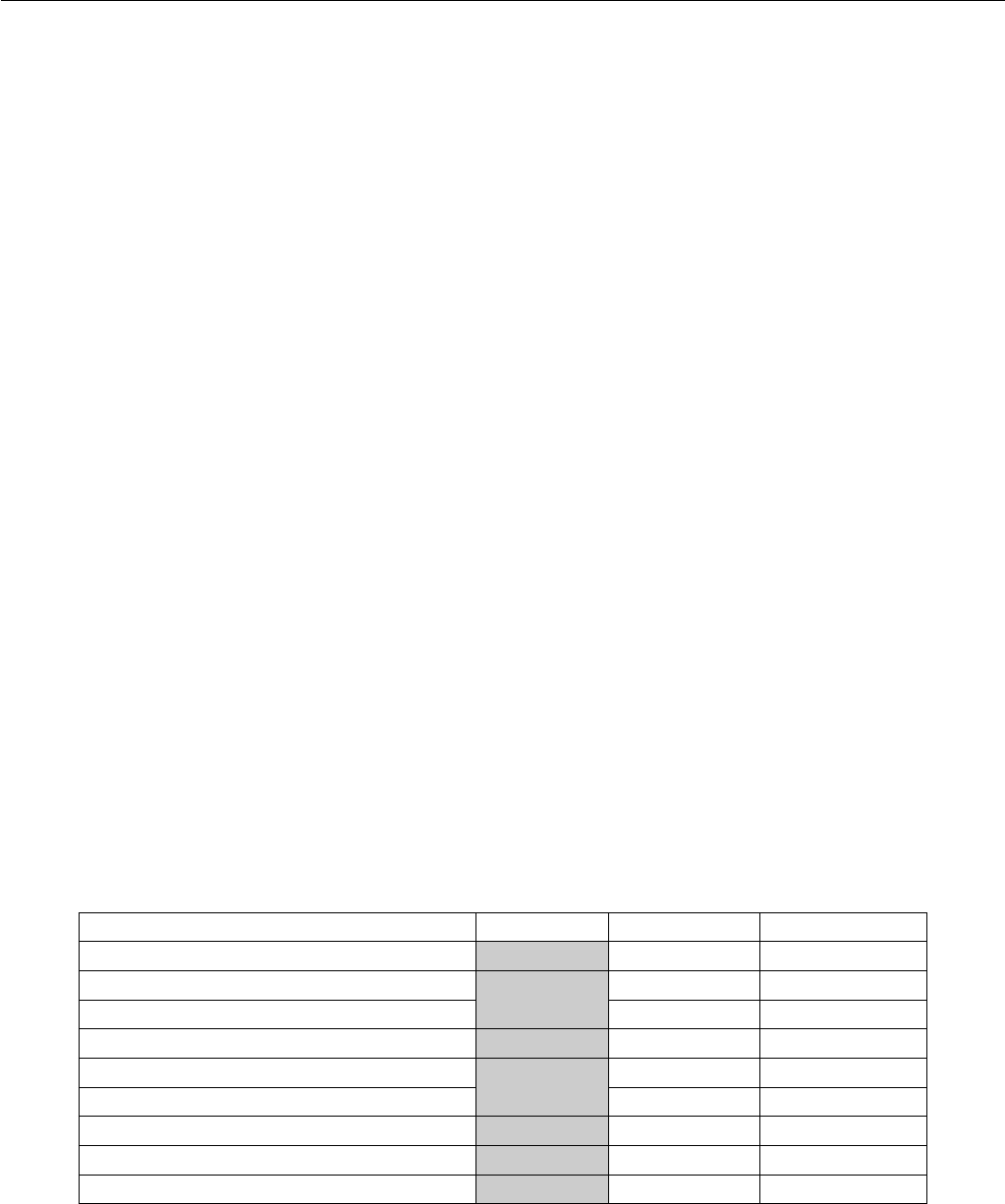

Eng (PPF) Eng (SP) German have + PP

OK with past temporal adverbs no yes yes

Event must be salient at UT yes no no

Result must be true at UT yes no no

Lifetime effects apply yes no no

Universal perfect must be true at UT yes n/a no (must not)

Event must be repeatable yes no no

OK in question about specific past no yes yes

OK in question about general past yes only w/ adv. only w/ adv.

OK in out of the blue question yes only w/ adv. only w/ adv.

4 Conclusion

• See the following page for a table summarizing our data.

Main observations:

• Questions are the main locus of variation between the four languages in our survey.

– Turkish and German require an additional adverb in out of the blue questions and in

questions about the general past; Tatar requires an alternate construction in these con-

texts.

– Only the Bulgarian expression can occur in out of the blue questions and in questions

about the general past; however, it cannot occur in questions about specific past times.

• Interestingly, all of the languages in our survey require that the state described by a verb in a

“universal perfect” expression be false at the utterance time.

Evaluation against existing theories of the (English) present perfect:

• “Extended now” (XN) theories (McCoard 1978, Dowty 1979, among others): XN the-

ories fail to account for our observed data for a number of reasons. These include (i) the

expressions’ ability to combine with temporal adverbs denoting far past times; (ii) the lack

of a salience requirement; and (iii) the lack of a requirement that result states hold at the

utterance time.

• “Definite times” constraint theory (Klein 1992): A constraint on having more than one

“definite time” relative to the utterance time is contradicted by the ability of the surveyed

expressions to (i) combine with temporal adverbs denoting specific past times; and (ii) occur

in questions about specific past times.

• Modal theory (Katz 2003): Katz (2003)’s modal theory of the present perfect cannot ac-

count for the ability of the surveyed expressions to occur in non-repeatable contexts (i.e.,

contexts in which it is impossible for the event to re-occur).

• Bottom line: Current theories of the (English) present perfect cannot account for the observed

Turkish/Tatar/Bulgarian/German data.

16

Towards a typology of the “present perfect” Bowler & Ozkan

Why not just call these simple pasts?

• As shown in the following table, the expressions in these languages pattern more like the

English simple past than the English present perfect.

• At present, we refrain from giving an explicit semantics for these morphemes. Our main

claim is that their distribution cannot be accounted for by current theories of the (English)

present perfect.

• All of the languages in our survey also have other expressions marking past times (e.g. Turkish

-DI, Tatar -DI). We are therefore hesitant to propose a simple past tense analysis for the data

here without considering the pragmatic implications for the languages’ tense systems as a

whole.

17

Towards a typology of the “present perfect” Bowler & Ozkan

Eng (PPF) Eng (SP) Turkish Tatar Bulgarian German

OK with past temporal adverbs no yes yes yes yes yes

Event must be salient at UT yes no no no no no

Result must be true at UT yes no no no yes no

Lifetime effects apply yes no no no no no

Universal perfect must be true at UT yes n/a no (must not) no (must not) no (must not) no (must not)

Event must be repeatable yes no no no no no

OK in questions about specific past no yes yes yes no yes

OK in questions about general past yes only w/ adv. only w/ adv only w/ EXIST yes only w/ adv.

OK in out of the blue questions yes only w/ adv. only w/ adv. only w/ EXIST yes only w/ adv.

18

Towards a typology of the “present perfect” Bowler & Ozkan

References

Bhatt, R. and Pancheva, R. (2005). LING 130: The syntax and semantics of aspect. Lecture notes,

LSA 130.

Chomsky, N. (1970). Deep structure, surface structure, and semantic interpretation. In Jakobson,

R. and Kawamoto, S., editors, Studies in Oriental and General Linguistics, pages 52–91. TEC

Corporation for Language and Educational Research.

Comrie, B. (1976). Aspect: An Introduction to the Study of Verbal Aspect and Related Problems.

Cambridge University Press.

S¸ener, N. (2011). Semantics and Pragmatics of Evidentials in Turkish. PhD thesis, University of

Connecticut.

Dahl,

¨

Osten. (1985). Tense and Aspect Systems. Oxford University Press.

Dahl,

¨

Osten. (2000). Tense and Aspect in the Languages of Europe. Empirical Approaches to Lan-

guage Typology. Mouton de Gruyter.

Dowty, D. (1979). Word Meaning and Montague Grammar. Kluwer.

Greed, T. (2009). Evidentiality in Tatar. Master’s thesis, University of Helsinki.

Iatridou, S., Anagnostopoulou, E., and Izvorski, R. (2001). Observations about the form and

meaning of the Perfect. In Kenstowicz, M., editor, Ken Hale: A Life in Language, number 36 in

Current Studies in Linguistics. MIT Press.

Izvorski, R. (1997). The present perfect as an epistemic modal. In Proceedings of Semantics and

Linguistic Theory 7.

Katz, G. (2003). A modal account of the English present perfect puzzle. In Young, R. and Zhou, Y.,

editors, Proceedings of Semantics and Linguistic Theory 13, pages 145–161.

Klein, W. (1992). The present perfect puzzle. Language, 68:525–552.

McCawley, J. (1981). Notes on the English perfect. Australian Journal of Linguistics, 1:81–90.

McCoard, R. (1978). The English Perfect: Tense-choice and Pragmatic Inferences. Elsevier, Amster-

dam/New York.

Musan, R. (2001). The present perfect in German: outline of its semantic composition. Natural

Language and Linguistic Theory, 19(2):355–401.

Pancheva, R. and von Stechow, A. (2004). On the present perfect puzzle. In Moulton, K. and Wolf,

M., editors, Proceedings of the North East Linguistic Society 34.

Plungian, V. (2011). Towards a typology of perfect and related categories. Slides, Salos-VIII.

Portner, P. (2003). The (temporal) semantics and (modal) pragmatics of the perfect. Linguistics

and Philosophy, 26:459–510.

Reichenbach, H. (1947). Elements of Symbolic Logic. Macmillan & Co., New York.

19

Towards a typology of the “present perfect” Bowler & Ozkan

San Roque, L., Floyd, S., and Norcliffe, E. (2015). Evidentiality and interrogativity. Lingua.

Straughn, C. (2011). Evidentiality in Uzbek and Kazakh. PhD thesis, University of Chicago.

Tatevosov, S. (2007). Evidentiality and mirativity in the Mishar dialect of Tatar. In Guentch

´

eva,

Z. and Landaburu, J., editors, L’Enonciation Mediatisee II: Le traitement epistemologique de

l’information: illustrations amerindiennes et caucasiennes, pages 407–433.

´

Editions Peeters.

Appendix: Perfect versus perfective

• A note on terminology: Perfect and perfective are two different things.

– Perfective: “Viewpoint aspect” that relates the runtime of an event to a time (following

denotation modified from Bhatt and Pancheva 2005).

(53) JPERFECTIVEK = λp

<v,t>

λt

<i>

. ∃e

<v>

[τ (e) ⊆ t & p(e) = 1]

e = event (of type v)

τ (e) = the runtime of the event

t = reference time; the time at which the proposition is taken to be true

(54) Leroy read the book in an hour.

– Perfect: Relates times; the focus of this presentation.

∗ Time terminology adapted from Reichenbach (1947):

ET = event time

RT = reference time

ST = speaking time

Present perfect: ET < ST,RT

(55) Present perfect: Leroy has read the book.

(56) Past perfect: Leroy had read the book by the time class finished.

(57) Future perfect: Leroy will have read the book by the time class finishes.

20