Purdue University

Purdue e-Pubs

.$,""$007$0$0 7$0$0 ,#(00$/1 1(-,0

,2 /6

e Historical Evolution of the German Present

Perfect from the Perspective of Complexity eory

and Emergent Grammar

Valentina Concu

Purdue University

-**-41'(0 ,# ##(1(-, *4-/)0 1 '8.0#-"0*(!.2/#2$$#2-.$, ""$001'$0$0

7(0#-"2+$,1' 0!$$,+ #$ 3 (* !*$1'/-2&'2/#2$$2!0 0$/3("$-%1'$2/#2$,(3$/0(16(!/ /($0*$ 0$"-,1 "1$.2!0.2/#2$$#2%-/

##(1(-, *(,%-/+ 1(-,

$"-++$,#$#(1 1(-,

-,"2 *$,1(, 7$(01-/(" *3-*21(-,-%1'$$/+ ,/$0$,1$/%$"1%/-+1'$$/0.$"1(3$-%-+.*$5(167$-/6 ,#+$/&$,1

/ ++ / Open Access eses

'8.0#-"0*(!.2/#2$$#2-.$, ""$001'$0$0

Graduate School Form 30

Updated 1/15/2015

PURDUE UNIVERSITY

GRADUATE SCHOOL

Thesis/Dissertation Acceptance

This is to certify that the thesis/dissertation prepared

By

Entitled

For the degree of

Is approved by the final examining committee:

To the best of my knowledge and as understood by the student in the Thesis/Dissertation

Agreement, Publication Delay, and Certification Disclaimer (Graduate School Form 32),

this thesis/dissertation adheres to the provisions of Purdue University’s “Policy of

Integrity in Research” and the use of copyright material.

Approved by Major Professor(s):

Approved by:

Head of the Departmental Graduate Program Date

Valentina Concu

The Historical Evolution of the German Present Perfect from the Perfective of Complexity Theory and Emergent Grammar

Master of Arts

John Sundquist

Chair

Jennifer Marston Williams

Jeff Turco

John Sundquist

Madeleine Henry

7/27/2015

THE HISTORICAL EVOLUTION OF THE GERMAN PRESENT PERFECT

FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF COMPLEXITY THEORY AND

EMERGENT GRAMMAR

A Thesis

Submitted to the Faculty

of

Purdue University

by

Valentina Concu

In Partial Fulfilment of the

Requirements for the Degree

of

Master of Arts

August 2015

Purdue University

West Lafayette, Indiana

ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

ABSTRACT ....................................................................................................................... iii!

CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................... 1!

CHAPTER 2. REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE ............................................................. 7!

2.1 Theoretical Descriptions of the Present Perfect ........................................................ 7!

2.2 The Present Perfect in Textbooks and Didactic Grammars ................................... 17!

2.4 The Grammaticalization of Linguistic Structure ................................................. 21!

CHAPTER 3. METHODOLOGY ................................................................................... 25!

3.1 Modern German ...................................................................................................... 25!

3.2 Old and Middle High German ................................................................................ 26!

CHAPTER 4. THE PRESENT PERFECT IN MODERN GERMAN ............................. 29!

CHAPTER 5. THE PRESENT PERFECT IN OLD AND MIDDLE HIGH GERMAN . 36!

5.1 Old High German .................................................................................................... 36!

5.2 Middle High German ............................................................................................. 42!

5.3 Discussion .............................................................................................................. 49!

CHAPTER 6. CONCLUSIONS ...................................................................................... 53!

REFERENCES ................................................................................................................. 57!

APPENDICES .............................................................................................................. 54!

Appendix A .................................................................................................................. 61!

Appendix B ................................................................................................................... 63!

Appendix C ................................................................................................................... 67!

iii

ABSTRACT

Concu, Valentina. M.A., Purdue University, August 2015. The Historical Evolution of the Present

Perfect from the Perspective of Complexity Theory and Emergent Grammar. Major Professor:

John Sundquist.

The purpose of this study is to understand the meaning of the present perfect in Modern German

and also, to trace its development in the early stages of German. Therefore, the synchronic

analysis, in which I analyze articles from a famous German magazine, is combined with the

diachronic study of the present perfect attestations in Old High German and Middle High

German. This study is conducted within a Complexity-Theory and Emergent Grammar approach

in which languages are viewed as dynamic system that changes over time, and grammar is seen as

an epiphenomenon and a result of communicative needs among speakers. This study shows that

German speakers use the present perfect with a particular pragmatic function, which started to

emerge already in Old High German. This work also highlights the relevance of diachronic

research for a deeper understanding of grammar, as well as the importance of a pragmatic

approach when addressing grammar in general.

1

CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION

In every language, the use of grammatical tenses is one of the most important parts of

every day communication, since it aids in understanding of every written or spoken text. The

tense system of a language is, indeed, a vital component of every speech act and “the language

itself requires us to use tenses in every sentence and often, more than one time” (Weinrich, 1964,

p. 8). In German, the present perfect in particular has drawn the attention of numerous scholars:

“wohl über kein anderes deutsches Tempus wurde so viel geschrieben wie über das Perfekt”

claims Michael Rödel (2007, p. 57) in his work about the double present perfect.

According to Duden, the present perfect is a “Zeitform, mit der ein verbales Geschehen

oder Sein aus der Sicht des bzw. der Sprechenden als vollendet charakterisiert wird;

Vorgegenwart; vollendete Gegenwart; Präsensperfekt” (a tense with a verbal event or state, which

is already completed from the point of view of the speaker; pre-past; complted past, present

perfect).

This construction, which started to be used during the Old High German period, is

formed by the combination of the auxiliary verbs haben and sein and the past participle:

(1) Sie hat ein Buch gelesen

She had a book read

‘She has read a book’

(2) Er ist nach Hause gefahren

He is home gone

‘He has gone home’

2

The German present perfect is used in numerous contexts, formal or informal, written or

spoken, as shown by the two examples below. The first, from the online version of the newspaper

Die Zeit, and the second is extracted from a blog about healthy cooking tips:

(3) “Das Wort Dekarbonisierung hatten bislang wohl die wenigsten Menschen in ihrem aktiven

Wortschatz. Das soll sich ändern: Im Laufe des Jahrhunderts – also spätestens bis zum Jahr 2100

– wollen die wichtigsten Industrienationen eine kohlenstoffarme Weltwirtschaft schaffen, um so

die schlimmsten Folgen des Klimawandels zu verhindern. Aber wie würde eine solche Welt

aussehen? Natürlich ist es vermessen, technische Entwicklungen auf 80 Jahre vorauszusagen. Im

Jahr 1930 hat beispielsweise niemand die Existenz eines Smartphones für möglich gehalten. Aber

einige grundsätzliche Entwicklungen lassen sich schon heute abschätzen. ZEIT ONLINE stellt

die wichtigsten vor:..”

2- “Guten Morgen! Isi: Ist ja mächtig warm bei Euch, für mich viel zu heiß! Freitag wars hier

sehr warm, gestern schon nicht mehr so warm, dafür sehr schwül, und da häng ich dann ja voll

durch. Bei uns hat es sich Gott sei Dank gestern abend abgekühlt!! Vanzi: Ich bin auch gespannt,

wie Dir die Roulade schmecken wird! Bei mir gibt's heute abend auch nur ne Suppe, weil ich

heute nachmittag zu Kaffee und Kuchen eingeladen bin. Ich hab mich für die Möhren-Kokos-

Suppe mit Mango entschieden! Schönen Sonntag! LG Elke.”

The first one can be considered formal writing, since it comes from a newspaper. The

second one is a more informal type of writing, since bloggers tend to use a language without

formalities. In both texts, we can find the present perfect. This suggests a large usage of this tense

in Modern German.

One of the most widely debated questions around the present perfect concerns its

meaning and function in Modern German. For instance, a large number of scholars ground their

descriptions using three parameters that Hans Reichenbach developed in 1947 to describe the

English temporal system: point of speech, point of reference and point of event. The point of

3

speech (S) is the moment in which the speaker or writer actually says or writes something, the

point of event (E) refers to the exact moment in which the particular event took place, and the

point of reference (R) is the time expressed by the conjugated verb form and is often specified by

temporal adverbs. In more resent research, Ehrich (1992), Helbig & Buscha (1998), Schumacher

(2005) and Rothstein (2007) define the German present perfect in terms of Reichenbach’s

parameters. They claim that the point of speech is at the same point as the point of reference in

the temporal axis, a feature that the present perfect shares with the present. The point of event is

back on the same axis, since the past participle connotes the action as temporarily situated before

the time when the speaker or writer reports it. Reichenbach’s parameters suggest that this tense is

able to express a resultative and punctual meaning only, since the action, no matter the verb used,

is situated before the moment of speech. This depiction seems to exclude automatically the usage

of the present perfect with present and future temporal references, which is instead quite common

in Modern German:

(4) Er hat sich damit jetzt als Politgangster entlarvt

He has himself with that now as Politgangster revealed

‘He revealed himself now to be a politgangster’

(5) Gleich habe ich es geschafft.

Soon have I it achieved

‘I will achieve it soon’

(Schumacher, 2005, p. 158, 161)

Weinrich (1964), Park (2003), Lombardi (2008) and Welke (2010) use a different

approach in the depiction of the present perfect, highlighting the pragmatic aspects involved in its

usage. Eva Clark (1990), as cited by Slobin (1994), claims, “when speakers choose an expression,

they do so because they mean something that they wouldn’t mean by choosing an alternative

expression” (Clark, 1990, p. 417). In the same way, when German speakers choose the present

4

perfect they mean something specific that they could not express if they would opt for another

tense, like the simple past for instance. That is why, no matter the register used, we can find a

large use of this tense in a large number of textual genres beside its copious implementation in the

spoken language.

As briefly summarized here, the answers available today about the meaning and the

functions of the present perfect are largely discordant. As observed by Alessandra Lombardi

(2008) in her work, Tempus der Wissenschaft, “die Ermittlung der semantischen Grundwerte der

Tempi, von Anfang an im Mittelpunkt des Interesses deutscher und italienischer

Tempusforschung, hat sich als echte wissenschaftliche Herausforderung erwiesen, welche zu

inhomogenen und noch bis heute umstrittenen deskriptiven Ergebnissen (Tempusdarstellungen)

geführt hat“ (p. 142). [The representation of the German tenses, which was from the beginning

the center of the interest of Italian and German tense’s research, became a real scientific

challenge, which led to controversial and inhomogeneous descriptive results]. This means that

today we are still dealing with a large divergence in methodologies and terminologies when it

comes to the depiction and the use of grammatical tenses and the present perfect in particular.

The large divergence in the depictions available also influences the way the present

perfect is taught in second and foreign language classrooms. As already observed by Latzen

(1977), “die Schwierigkeiten […] haben vor allem eine Hauptwurzel, nämlich: die nicht

zureichende Beschreibung des Gebrauches der Tempora in den didaktischen Lehrwerken und in

den dem Lehrenden normalerweise zugänglichen oder verständlichen Grammatiken” (1997,

p. 67). [the difficulties have above all a main origin: the insufficient description of the use of

tenses in didactic material and in the grammars accessible to students] Also Nicole Schumacher

(2005) noticed that “Bemerkswert ist nun, dass gerade die Tempora in Lerngrammatiken, in den

wenigsten Fällen, in einer transparenten Weise dargestellt werden. Sie werden nicht so

präsentiert, dass Zusammenhänge von Formen und Bedeutung sichtbar werden” (2006, p. 17).

5

[surprisingly, the description of the German tenses in didactic material doesn’t offer a clear and

transparent connection between form and meaning]. For example, the possibility to express future

meaning with the present perfect is often not mentioned at all, while the preterite is always

defined as the tense of written German (Concu, 2015).

In order to better understand which theoretical approach better describes functions and

meanings of this tense, it seems reasonable to look at how German speakers use this tense today

in written texts. But because “demonstrating that a given form or construction has a certain

function does not constitute an explanation for the existence of the form or construction; it must

also be shown how that form or construction came to have that function” as claimed by Bybee,

Perkins and Pagliuca (1994, p. 3). In other words, a synchronic analysis has to be supported by a

diachronic investigation as well. For this reason, after determining which function the present

perfect has today, I will address the historical evolution of this tense from its first examples in

Old and Middle High German.

Combining synchronic with a diachronic analysis is an approach imbedded in a

Complexity Theory and Emergent/Usage-Based Grammar perspective, which views linguistic

patterns as “epiphenomena of interaction” (Larsen-Freeman and Cameron, 2008, p. 81). In other

words, grammatical forms emerge as a result of communicative behavior between speakers of a

specific language. “Language change is not just a peripheral phenomenon that can be tacked on to

a synchronic theory; synchrony and diachrony have to be viewed as an integrated whole” (Bybee,

2010, p. 105). If the present perfect has a specific pragmatic function today, the origin can be

tracked down along with the pattern of its development that was determined through how

speakers made use of it over the last centuries.

The goal of this work is to gain understanding of the historical reasons behind the modern

meaning and function of this construction. In particular, this work will focus on three specific

questions:

6

1) How is the present perfect used in Modern German written texts?

2) What are the origins of the meaning and functions of the present perfect?

3) How did these functions develop over time?

The structure of this thesis is as follows: The second chapter provides a background of

the present perfect in theoretical and didactic works and Complexity Theory. This chapter serves

as a review of the literature about the German present perfect and some important processes

involved in the evolution and development of grammatical structure over time. The third deals

with the methodology used in both synchronic and diachronic analyses. The fourth deals with

Modern Standard German texts and the use of the present perfect in a corpus of magazine articles.

The fifth chapter is an overview of the historical development of the present perfect and its

origins in the earliest stages of the language.

7

CHAPTER 2. REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

In the first part of this chapter, I will present an overview of the theoretical and didactic works

about the present perfect in order to provide a background on the way this tense is often

described. In particular, I discuss several theoretical analyses of present perfect from different

perspectives. In the first part, I discuss important contributions from Reichenbach, Schumacher

and Weinrich. In the second part, I describe how various teaching and learning material describe

the present perfect in didactic material in German textbooks and didactic grammars. The second

part will deal with the application of a Complexity Theory approach to the process involved in the

historical development of grammatical structures. The goal of the chapter is to present an

overview of how different and contradictory the various descriptions of the present perfect are in

the modern descriptions of this grammatical tense. In addition, this chapter provides theoretical

background on the historical development as it pertains to Complexity Theory and

grammaticalization.

2.1 Theoretical Descriptions of the Present Perfect

Reichenbach’s three parameters. One of the most influential works about tense was written in

1947 by the philosopher and scientist Hans Reichenbach, who developed in his work Elements of

Symbolic Logic (1947) a system of three parameters to describe the English temporal system. As

pointed out in the introduction, the three different parameters elaborated by Reichenbach to

describe the grammatical tenses in English are: the point of speech (S), which is the moment

8

when the speaker or writer actually says or write something, the point of to the exact moment

when the particular event took place, and the point of reference (R), which is the time expressed

by the conjugated verb form and it is often specified by temporal adverbs. The relation between

the point of speech and the point of reference is expressed by means of the time concepts of

present, past and future. The examples below are the representation of the English tenses as

depicted by Reichenbach. In the first line we can find the grammatical term for that specific tense,

in the second the temporal axes with the three points and in the last, an example from Modern

English:

Present Simple Future Future Perfect

I see John I will see John I shall have seen John

------X-----> ---X---------X--> ----X----X-----X-->

S, R, E S, R E S E R

Past Perfect Simple Past Present Perfect

I had seen John I saw John I have seen John

----X---X----X--> ---X--------X--> ----X-------X------>

E , R S R, E S E S, R

(Reichenbach, 1947)

In the case of the present, (S) and (E) are on the same point along the temporal axis while in the

case of future, (S) is behind (E) and (R). The difference between the past simple and the present

perfect is the position of both (S) and (R). In the first, (R) is behind (E) and (S), while with the

present perfect is (R) behind both (E) and (S).

9

The same parameters are also adopted in German linguistics for the description of the tense’s

system. Several German scholars like Ehrich (1992), Helbig & Buscha (1998) and Rothstein

(2007) use these three points to describe the present perfect. Ehrich (1992) describes the present

perfect putting (E) before (<) (R) and (S):

(1) Ich habe die Tür zugemacht

I’ve the door closed

‘I have closed the door’

E< R, S

(Ehrich, 1992)

Helbig & Buscha (1998) and Rothstein (2007) also put (E) before (R) and (S). In the two

examples below we find the temporal axis again with the points positioned on it:

(2) Peter ist eingeschlafen

Peter is fallen asleep.

‘Peter has fallen asleep’

--------E-----------S/R----

(Helbig & Buscha, 1998)

(3) Gestern ist er spät nach Hause gegangen

Yesterday is he late home come

‘He has come home late yesterday’

--------E-----------S/R----

(Rothstein, 2007)

10

In all three descriptions, the point of speech is at the same point as the point of reference, a

feature that the present perfect shares with the present. The time of the event is placed earlier

along the temporal axis, since the past participle expresses that the action has happened in a

moment before the speaker or writer describes it.

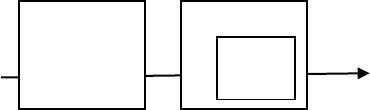

Nicole Schumacher (2005) also pictures the present perfect in the same way. She uses the

German denomination for the three points described by Reichenbach: Äußerungszeit (ÄZ - point

of speech), Tempuszeit (TZ - time of reference) and Situationszeit (ST - time of event). In her

depiction we find the temporal axis with an arrow that indicates the time’s flow. On the temporal

axis Schumacher puts the three parameters which are depicted here as small boxes:

(4) Er hat sich damit gestern als Politgangster entlarvt.

He had himself with that yesterday to be a politgangster revealed

‘He revealed himself yesterday to be a politgangster’

Figure 1: The present perfect by Schumacher (2005, p. 154)

The parameters establish the point of the event before the point of speech. However, as shown by

Schumacher, this is not the only combination possible, since the present perfect is used by

speakers to express present and future meanings, as shown in the following example:

SZ

TZ

ÄZ

11

(5) Es hat sich damit jetzt als Politgangstar entlarvt

He had himself now to be a politgangster shown

‘He revealed himself now to be a politgangster’

Figure 2. The present perfect expressing present meaning (Schumacher, 2005, p. 161)

According to Schumacher (2005), the present perfect allows resultative present and future

meanings. As also claimed by Wunderlich (1970), “einige der Tempusmorpheme sind -isoliert

genommen- in überraschender Weise vieldeutig und sind erst in ihren jeweiligen Kontexten durch

pragmatische Faktoren, die durch die Sprachsituation bzw. den Äußerungstyp und die

Zeitbestimmungen (Adverbien) interpretierbar sind” (p. 118). [some of the temporal morphemes

– if taken in isolation - have surprisingly different meanings that can be interpreted only if they

are inserted into a determined context with the aid of pragmatic factors, which can be understood

through the type of situation, the kind of expressions and the temporal (adverbs) indications].

However, the fact that the actions expressed in present and in future by the present perfect have

perfective features does not necessarily mean that the present perfect itself determines if the

action expressed by the verb has the same feature in relation to the grammatical category of

aspect. The question now is: how does German realize perfective (the action is seen as a whole

and with specific temporal boundaries) and imperfective (the action has no specified temporal

limits) meanings.

TZ

SZ

ÄZ

12

Aspect in German. In German aspect can be expressed by separate lexical entries. German verbs

are classified in different subgroups of a particular category called Aktionsarten (type of actions).

The actions expressed by the verbs in these subgroups have defined and specific temporal

boundaries. The difference between them can be seen when comparing two verbs like

telefonieren (to talk on the phone) and anrufen (to call someone on the phone):

(6) Als wir nach Hause gekommen sind, hat Paolo Giulio angerufen

When we home come are, has Paolo Giulio called

‘When we came home, Paolo was calling Giulio’

(7) Als wir nach hause gekommen sind, hat Paolo mit Giulio telefoniert

When we home come are, has Paolo with Giulio talked on the phone

‘When we came home, Paolo was talking on the phone with Giulio’

In English the difference between the two sentences is determined by the verbs and the

two tenses that can be used (present perfect vs. present progressive). In German, the different

duration of the action is determined by the two separate verbs telefonieren vs. anrufen, although

in both sentences the same tense is used. This means that the present perfect can convey both

meanings, perfective and durative, and the duration of an action is indicated by the specific verb

that is used.

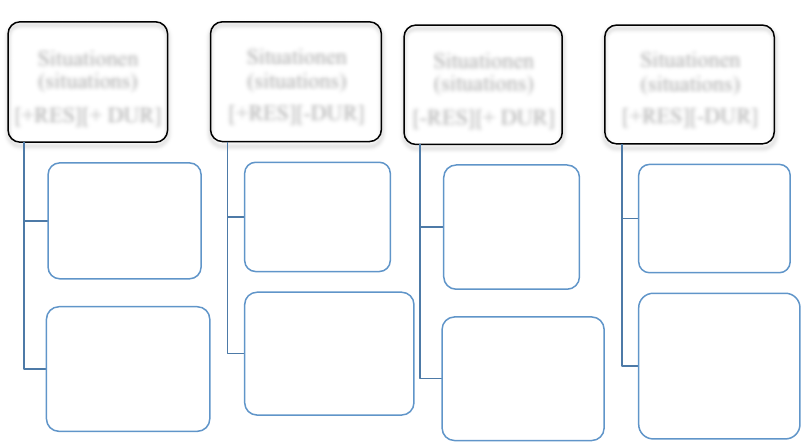

Various scholars classify situationtypen differently: Veronika Ehnrich (2007), for

example, classifies them in features, actions and activities. The first refers to specific

characteristics like blond sein (to be blond) while the latter is depicted as follows:

13

Situationen

(situations)

[+RES][+ DUR]

Aktionen

(actions)

ein Haus bauen

to build a house

Prozesse

(processes)

genesen

(to recover)

Situationen

(situations)

[+RES][-DUR]

Akte

(acts)

eintreten

to go in

Vorkommnisse

(occurencies)

finden

(to find)

Situationen

(situations)

[-RES][+ DUR]

Aktvitäten

(activites)

tanzen

(to dance)

Zustände

(states)

sitzen

(to sit)

Situationen

(situations)

[+RES][-DUR]

Akte

(acts)

husten

to cough

Vorkommnisse

(occurencies)

aufschrecken

(to startle)

Figure 3: The classification of the situationstypes based on Ehrich (1992)

The main criterion for this classification is “resultative” [+/-RES]. [+RES] verbs denote

the achievement of a goal or a state and can be also classified as “+ durative” and “- durative”:

[+DUR] verbs like genesen (to recover) or [-DUR] like finden (to find). [-RES] verbs don’t imply

any realizations and don’t specify clearly the beginning or the end of the specific activity. These

verbs are divided in [+/-DUR]. [+DUR] verbs like tanzen (to dance) imply a longer activity then a

[-DUR] verb like husten (to cough).

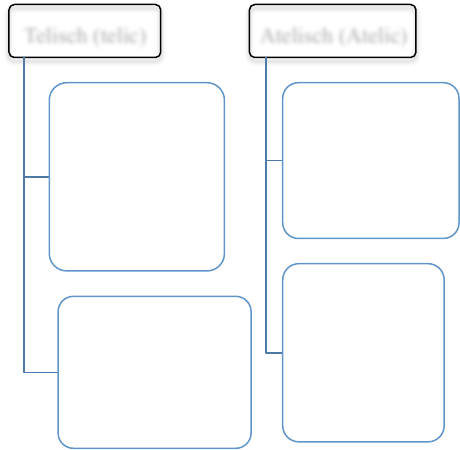

Nicole Schumacher uses slightly different terminology. She uses the term Situationtypen

(types of situations), which she describes as follows: “durch die lexikalische Bedeutung des

Verbs im Zusammenhang mit seinen Argumenten und Modifikatoren realisierte Kategorie, die

die inhärente Grenzbezogenheit einer beschriebenen Situation bestimmt. Einem telischen

Situationstyp ist eine Grenze inhärent, einem atelischen Situationstyp ist keine Grenze ihnärent”

(Schumacher, 2005, p. 151). [categories, which as realized through their lexical meaning together

with their modifiers and arguments, which defines the temporal boundaries of a situation. No

14

specific temporal boundaries are specified in the case of an atelic situation type. In the contrary,

with telic situation types these boundaries are implied]. The basic parameter in Schumacher’s

description is telicity and the difference between a telic and an atelic verb can be observed again

in the comparison between anrufen and telefonieren. Schumacher’s classification system is

provided as follows:

Figure 4: The classification of the Sytuationtypes based on Schumacher (2005)

The telicity of a specific situation, although potentially contained in the verb, is not

always realized. The presence of a direct object (den Apfel essen vs. essen – to eat an apple vs. to

eat), of a numeral adjective (ein Apfel essen vs. Äpfel essen – to eat an apple vs. to eat apples) or

of a preposition (schlafen vs. auf dem Bett schlafen – to sleep vs. to sleep on the bed) determines

the perfective of imperfective reading of the specific event expressed by the verb (Schumacher,

2005).

In German there are the lexical features of the verbs that carry information about the

duration of an action, and not the tense itself. As highlighted by Schumacher (2005), “Das Perfekt

Telisch (telic)

Achivements

[-DUR][+DYN]

sich entlarven

(to reveal one's

true charachter)

schaffen

(to achieve)

Accomplishment

[+DUR][+DYN]

ein Buch lesen

(to read a book)

verstummen

(to fall silent)

Atelisch (Atelic)

Activities

[+DUR][+DYN]

Cds brennen

(to burn cds)

schneien

(to snow)

States

[+DUR][-DYN]

wohnen

(to live)

tot sein

(to be dead)

15

beinhaltet keinen aspektualen Wert in Bezug auf Perfektivität/Imperfektivität in seiner

Konstruktionsbedeutung, d.h. es enthält keine Festlegung dahingehend, ob eine Situation mit oder

ohne einen Endpunkt perspektiviert wird. Deshalb kann das Perfekt perfektive und imperfektive

Vergangenheitslesarten realisieren” (p. 174). [the present perfect contains no spectual values in

relation to perefectivity and imperefectivity in its construction’s meaning. This means that it does

not incorporate any fixing properties about the duration of the action expressed by the verb.

Therefore the present perfect can express both past perfective and imperfective meainings].

Time of Comment and Time of Narration. Harald Weinrich wrote another relevant

work on the German tenses in 1964. In his book, Tense: narration and comment, he suggested a

completely different approach to the function and meaning of the German tenses. He divided

them into two different groups, namely, the group of comment and the group of narration. In the

group of comment, we find the present and the present perfect, while in the tense group of

narration, we find the simple past and the past perfect. The main difference between these two

groups reflects the intent of the speaker or writer: when he or she wants to comment on

something, the tenses of the first group will be used. When he or she wants to tell a story, then the

tenses of the second group will be used. Weinrich also discusses the different attitude of the

speaker and the listener. There will be more expectant in the case of the comment and more calm

and relaxed in the case of narration. The tenses of the first group are used in dialogues, poetry,

scientific essays and so on. The tenses of the second group are used in stories, narration (spoken

or written), historical documentation and so on. According to Weinrich, German tenses carry out

specific pragmatic and communicative functions, which reflect the perspective of the speaker in

relation to the information contained in the texts. It is not the mode of communication, (spoken or

written) which determines the choice of one tense instead of the other, but the communicative

intentions of the writer or speaker.

16

Other scholars follow Weinrich’s theory and relate these differences to aspect of

narration. Klaus Welke (2010) from the Humboldt University in Berlin claims that „das Perfekt

ist auf Grund seiner spezifischen semantischen Eigenschaften das Tempus des konstatierenden

Berichten [vom Vergangenen] und das Präteritum auf Grund seiner spezifischen semantischen

Eigenschaften das Tempus des fortlaufenden Erzählen [vom Vergangenen]“ (p. 22). [The present

perfect is the past tense of the comment because of its semantic features, while the preterite is the

past tense of the narration because of its semantic features]. In the same way, Schumacher (2005)

also asserts that „die Differenz [zwichen Perfekt und Präteritum] liegt in der subjektiven,

sprecherbezogenen Dimension der Distanz begründet, die sich durch Weinrichs (1993) Konzepte

des Erzählens und Besprechens erfassen last“ (p. 191). [The difference between Present Perfect

and Preterite lies in the subjective dimension of “DISTANCE”, which refers to Weinrich's

categories of comment and narration] and „um die Gebrauchspräferenzen von Perfekt und

Präteritum in Vergangenheitskontexten zu veranschaulichen, sind nicht mehr temporale und

aspektuale Phänomene, sondern die Subjektive Ausprägung von Distanz herauszuziehen“

(Schumacher, 2011, p. 22). [In order to highlight the usage differences between preterite and

present perfect, the temporal and aspectual phenomena do not have to be considered, but the

subjective markedness of the “DISTANCE”].

These claims show a lot of similarities with what Harald Weinrich theorized in his work:

the usage of the tenses reflects the subjectivity of the speaker or writer and his or her relation to

the information that he or she wants to communicate. The transition from a part with present

perfect to another with simple past reflects the writer’s change of perspective. The same

observations have been made for the English language in relation to the main difference between

the same tenses, present perfect and preterite. As claimed by Eva Clark (1990), if the speakers

choose preterite instead of present perfect they mean something slightly different that the other

tense wouldn’t be able to express and vice versa.

17

In this brief analysis, it can be observed that there are two main different directions in the

depiction of the present perfect. The first one grounds in the representation of the tense through

Reichenbach’s parameters situated on the temporal axis, which implies a direct connection

between grammatical tenses and the category of time. The second one puts emphasis on the active

role of the speaker, which is aware of the pragmatic values involved in the use of the present

perfect and uses it to express something specific that it couldn't be express using another tense.

2.2 The Present Perfect in Textbooks and Didactic Grammars

As can be seen in previous sections of this chapter, the present perfect in German

conveys various meanings, is used in various grammatical contexts and occurs in a wide variety

of registers. The theoretical discussion above shows the complicated nature of this topic. As is

evident in theoretical materials, learners are exposed to this variety of views in material for

German as a foreign language. In order to demonstrate the different and conflicting view of the

present perfect is described in pedagogical material, several different German textbooks and

grammars were analyzed. All textbooks were written for learners of German as a foreign

language in the United States:

• Deutsch heute (3

rd

Edition)

• Assoziationen

• Alles klar

• Wie geht’s?

• Stationen

• Kontakte (5th Edition)

• Kaleidoskop (8

th

Edition)

• Vorsprung (3

rd

Edition)

18

The analysis of these textbooks used here show a simplistic way to describe the present

perfect in comparison to what the theoretical works analyzed previously. All the material

analyzed refers to it as the tense for spoken German, used in informal contexts and conversations

with family and friends. The usage of this tense to express present and future meaning is not

mentioned at all. This kind of depiction supports also a binary opposition between present perfect

and preterite, emphasizing the misleading assumption that the difference between them simply

lies in the mode (spoken vs written) and in the context (formal vs. informal). As examples of how

the present perfect is treated, consider three of the textbooks that were explored:

1. Augustyn, P. & Euba, N. (2008) Stationen. Cengage Learning: in this textbook the

present perfect is described as “the conversational way to speak and write about past

events in German”.

2. Terrell, T.; E., Tschrner; Nikolai, B. (2003). Kontakte (Fifth edition). Mcgraw-Hill: this

textbook claims that “in conversations, German speakers generally use the perfect tense

to describe past events”.

3. Moeller, J.;Adoph, W. (2013). Kaleidoskop (Eighth Edition). Cengage Learning: in this

textbook the present perfect tense is depicted as follows: “The present perfect is also

tense is often called the conversational past because it is used most frequency in

conversation to refer to events in past times. Is also used in informal writings such as

personal letters, diaries, and notes, all of which are actually a written form of

conversation”.

The didactic grammars analyzed here, normally used to allow students to deeply focus

exclusively on grammatical structures, were all published in Germany and are used in DAF

(German as a Foreign Language) in Germany and in different European universities:

• Übungsgrammatik Deutsch als Fremdsprache

• Übungsgrammatik Deutsch als Fremdsprache für Fortgeschrittene

19

• Übungsgrammatik der deutschen Sprache

• Lehr und Übungsgrammatik der deutschen Sprache

• Deutsche Grammatik. Ein Handbuch für den Ausländerunterricht

• Grammatik mit Sinn und Verstand

• Deutsche Grammatik. Laut. Wort. Satz.

• Deutsche Grammatik

• Deutsche Grammatik. Ein völlig neuer Ansatz

The depictions of the present perfect seem a little bit more exhaustive than the

descriptions in the textbooks from the previous section. The present perfect is described as the

tense for complete actions in the past, which means that it gives the events expressed by the verbs

a perfective meaning. Almost all grammars also mention the ability to express present and future

meanings with this tense, giving a more complete view of the possible uses of the present perfect.

As examples of didactic grammars that were explored, consider the following three examples:

1. Helbig, J. & Buscha, J. (2001). Deutsche Grammatik. Ein Handbuch für den

Ausländerunterricht. Berlin: Langenscheid. Present perfect: Bezeichnung eines

vergangenen Geschehens. Bezeichnung einer vergangenen Geschehens mit

resultativem Charakter. Bezeichnung eines zukünftigen Geschehens (In this

grammar the present perfect is described as a tense that can express not only past,

but also future meaning. In both cases the action is described as perfective.).

2. Hentschel, H. (2010). Deutsche Grammatik. Berlin/ New York: Walter De

Gruyter. Present perfect: Das Perfekt gehört zur grammatischen Kategorie

Tempus. Die Perfekttempi signalisieren, dass eine Situation vorzeitig zur eine

Referenzzeit noch relevant ist (The present perfect is used to express events in the

20

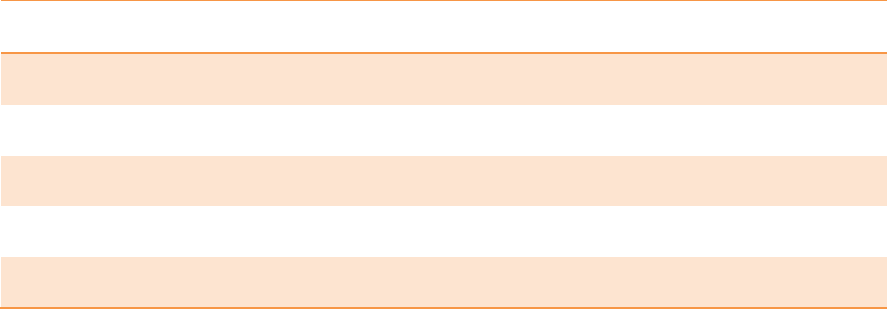

!"#!$%%&'"!!

#$%&'()*+$,)-!!

.,/$'0)-!

()(*+!)+,-.*//*.'"!

!#$,%&'()*+$,)-!!

1&'/&2*+%&!0&),+,3!

!!1)(*4!1'&(&,*4!56*6'&!!

0)1-2)'!)+,3%.&'"!!

1&'/&2*+%&!),7!.08'&/&2*+%&!0&),+,34!1)(*4!

1'&(&,*!),7!56*6'&!

3")1.)+45,3"0+4"5,6*.&5,0%/$*.()"!

!9&,(&!$/!#$00&,*!

1'&(&,*!1&'/&2*!

past that are still relevant to the reference time, which is the time expressed by

the conjugated verb form and it is often specified by temporal adverbs).

3. Dreyer, H. & Schmidt, R (2009). Lehr und Übungsgrammatik der deutschen

Grammatik. Ismaning: Max Hueber. Present perfect: Sprechtempus für

vergangene Handlungen, Vorgänge, Zustände. Sprechtempus auch schriftlich in

der direkten Rede. Für Informationen, die zeitlich vor einen allgemeinen gültigen

Aussage stehen (This grammar defines the present perfect using the register: it is

a Sprechtempus (speech tense), but is can be also used in the written language in

direct speech acts).

2.3 Discussion

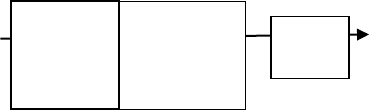

The analyses of the different material in this first part displays divergences not just between the

different categories of material (theoretical works, teaching material and didactic grammars), but

also inside the same category, where depictions sometimes seem to contradict themselves. The

graph below offers a visual representation of the results obtained:

Figure 5: The different depictions of the German present perfect

21

There is a lot of divergence in the way the meaning and the functions of the German

present perfect are depicted in the material analyzed here. In particular, the textbooks in section

2.2 offer a simplistic and misleading view of this tense, defining it as the tense for conversation

and informal contexts. The didactic grammars do a little bit better in the comparison, giving an

ampler picture of the uses of the present perfect. Lastly, the theoretical works, as already

mentioned, can be divided in two groups. One uses the three temporal points originally elaborated

by Reichenbach and describes grammatical tenses along a particular spot on the temporal axis.

The other involves pragmatics and a definitely more active role of the speakers who are aware of

the meanings and functions of every tense and use them to express their attitude in relation to the

information they are communicating.

2.4 The Grammaticalization of Linguistic Structure

In the previous two parts of this chapter, we looked more closely at ways in which the

present perfect in Modern German is described. The question I want to deal with now is, how its

meaning and functions came into being over time or, in other words, I want to focus on the

grammaticalization of the present perfect as a commentary tense, using Weinrich’s terminology.

Grammaticalization refers to the process whereby new constructions come to be used in a

language because of the reanalysis of them through the increased frequency of usage. The

construction acquires a new meaning, which allows the growth of the number of contexts in

which it can be used. Grammaticalization also highlights the dynamic feature of languages and

the historical changes in which they are involved. Grammaticalization can be seen as a part of the

of the Emergent Grammar framework, as theorized by Hopper in 1999. At the same time, it can

be considered compatible with a Complexity-Theory approach, which sees languages as complex

adaptive systems: “When linguistic structure is viewed as emergent from the repeated application

22

of underlying process, rather that given a priori or by design, then language can be seen as a

complex adaptive system” (Bybee, 2010, p. 2).

Complexity Theory offers a new approach to applied and historical linguistics today,

fostering a change in the way we look at human languages. In particular, Complexity Theory

views languages as continuously evolving systems with emergent structures, developed through

usage and repetition. “From a complexity theory perspective, a language at any point in time is

the way it is because of the way it has been used” (Larsen-Freeman and Cameron, 2009. p. 80). In

this perspective also human languages are viewed as complex adaptive systems, which interact

with their environment, adapt to it through self-organization and, as a result of these processes,

they change over time. Larsen-Freeman and Cameron underline the dynamic nature of the human

languages in their work “Complex Systems and Applied Linguistic” and consider the linguistic

patterns as “epiphenomena of interaction”, emphasizing in this way the essential roles of the

agents and their contribution to language change and evolution. Human languages are no longer

studied as an autonomous set of grammar rules developed on their own and learned by speakers

of a specific linguistic community. but they are rather viewed as dynamic systems strictly related

to their speakers and to their environment. The authors highlight that “language structure is

shaped by the way that language is used” (Larsen-Freeman and Cameron, 2009, p. 93), and,

quoting Nettle’s, claim that “the structure of language has emerged from the kind of message

speakers wish to convey and the kind of cognitive, perceptual, and articulatory mechanisms they

have to convey them, either by biological evolution, or cultural evolution, or more likely by some

combination of the two” (Nettle, 1999, p. 12).

Complexity theory draws attention to the strong connection between speakers and

languages and how the first influences the seconds and vice versa. Larsen-Freeman and Cameron

explain magisterially this phenomenon when they claim that “language emerges upwards in the

sense that language-using patterns arise from individuals using the language interactively,

23

adapting to another’s resources. However, there is reciprocal causality, in that the language-using

patterns themselves, downwardly entrain emergent patterns” (Larsen-Freeman and Cameron,

2009, p. 80). In other words, a Complexity-Theory historical linguistics approach assumes that

both synchronic and diachronic analyses should be combined, because “language change is not

just a peripheral phenomenon that can be tacked on to a synchronic theory; synchrony and

diachrony have to be viewed as an integrated whole” (Bybee, 2010, p.2).

Because of the importance of combining synchronic and diachronic analyses, the study of

the development patterns involved in the grammaticalization of grammatical structure is vital to

understanding how linguistic constructions came to have their modern meaning and functions.

Different scholars have studied this phenomenon focusing on different languages. In particular,

Bybee (2003), studied grammaticalization of the verb “can” from the Old English Era to Modern

English. In her article “Mechanisms of Change in Grammaticization: The Role of Frequency”,

Bybee describes how the increase of frequency of use of a specific grammatical structure

contributes to the loss of the semantic force of the particular structure. This process is called

semantic bleaching or generalization and implies the loss of specific features of meaning. As a

consequence, the number of contexts in which the structure can be used increased progressively.

The verb “can” in Old English was used to expresses various types of knowing and with a noun

denoted a person, a skill, or a language. The sense of knowing came from knowing an

acquaintance or an acquired knowledge or skill. Cunnan had very limited use with infinitive

objects in the Old English period and it was used with just three semantic classes of verbs. Due to

the bleaching of meaning, it started to be used in combination with an increased number of verbs.

As noticed by Bybee (2003), the Chaucer texts reveal that the use of can with infinitives has

expanded to other semantic classes of verbs. These include verbs denoting states of mind that are

not strictly intellectual, like love, suffer and have patience; verbs denoting states that are not

mental or emotional; finally, verbs indicating a change of state in another person and verbs

24

indicating an overt action like to ride, to go, to send, to climb, to steal, etc. New pragmatic

associations are now available to this verb, which is capable of taking on new discourse functions

that arise from the contexts in which it is commonly used. The verb “cunnan” also underwent

phonological reduction due to the frequency of use and today has the modern form of “can”. The

loss of specific semantic nuances allows the formation of new combinations with this verb and

contributed to the acquisition of the modern meaning and function of this modal verb.

A Complexity-Theory approach takes into account such dynamic processes (like

grammaticalization) that are involved in the historical changes in a specific language, since they

are not mere descriptions based on synchronic observations, but they also provide a satisfactory

explanation of “why” these structures are the way they are today. The role of frequency is also

relevant in this approach, since influences the meaning and the morphology of the units involved

and contributes to language change. An increased frequency may cause, for instance, the

weakening of semantic values and may determine the further development of a particular

structure, which will emerge in new context and with a different meaning.

The goal of this work is, indeed, not only to understand the meaning of the German

present perfect, but also to gain some insights into how this tense came to have the meaning it has

today in Modern German. Therefore, a Complexity-Theory approach can be considered as the

most suitable for the purpose of this thesis, because it also emphasizes the role of the speakers in

these evolutionary processes, seeing both speakers and languages as a whole and not as separated

entities.

The next two chapters focus on both synchronic and diachronic observations on the

German present perfect on written texts from different historical periods of this language.

25

CHAPTER 3. METHODOLOGY

In this chapter, I will present a description of the texts that I have included in my analyses

and the way I went through them in order to find evidences for my claims. Since this study

contains both synchronic and diachronic sections, I will present first the text from Modern

German and then, the texts from Old and Middle High German. The main purpose of this chapter

is to explain why I have chosen this particular corpus and which examples were relevant for my

analysis.

3.1 Modern German

The analysis on Modern German was based on 25 articles of Der Spiegel, one of the most

well known magazines in Germany, which deals with a significant amount of topics concerning

politics, economy and society. The particular issue that I analyzed is from November 2013.

The reason behind my selection is because I wanted to include texts written in a variety

close to Standard German, in order to avoid strong dialect influence. I say “strong” because I’m

well aware of the fact that every speaker cannot lose completely all the diatopic features from the

area she or he comes from, even if they are less visible in written forms of communication. This

could be seen as one of the limitations of this work, but also as a more general one when we

approach written texts. Another limitation of which I’m aware is that the articles I chose cannot

offer a complete view of the usage of such tenses in German today. They can give a certain idea,

26

which is also valuable, but a much larger number of texts needs to be taken into consideration if

we want to get a better understanding of this topic.

In these articles, I looked at the preterite and the perfect forms. For what concerns the

present perfect, I didn’t include the forms found in direct speech because I wanted to focus on the

journalist’s writing and the way she or he uses both tenses to communicate particular uses. I

wanted to to show that in some of the articles, the amount of the first were higher and in others,

the amount of the latter was larger. Furthermore, I especially focused on an article, Herr

Meinhardt ist frei (Mister Meinhardt is free; the full article can be found in Appendix C) This

article deals with the right-wing conservative politician Patrick Meinhardt at the end of his career,

after his party lost the election in Baden-Württemberg. The analysis of this particular text was not

just a mere count of forms. I also looked at the type of information that was present in that

particular section that showed a higher number of various tenses. For instance, in the parts in

which the author was narrating the biography of the politician, the number of simple past forms

were higher than present and present perfect forms. In the other parts of the article, we can find a

higher number of present and present perfect instead.

3.2 Old and Middle High German

The part that focuses on the diachronic analysis contains texts from the Old and Middle High

German periods. These texts were particularly useful for finding evidence about the

grammaticalization of the German present perfect. Due to the nature of this work, the corpus will

be limited to three texts from the Old High German period, and two from the Middle High

German period. I chose these particular texts because they are similar in genre and they are not

translations from any Latin work. They are also representative of these periods of the history of

German. All the texts are in poetic form. This insures a homogeneous type of text to work on. If

27

textual similarities are found, there is a higher possibility that the examples are well established

and could be considered acceptable evidence for the study in this thesis. The works included here

are:

Old High German:

• Hildebrandslied

• Ludwigslied

• Muspilli

Middle High German:

• Nibelungslied

• Der arme Heinrich

The first two are heroic Old High German lays, the Hildebrandslied (The Lay of

Hildebrand) and the Ludwigslied (The Lay of Ludwig) and the third, is the remaining part of the

an epic poem called Muspilli. The first was written around 820 AD “on the blank front and back

pages of a Latin manuscript from the monastery of Fulda and is written in an impossible mixture

of High and Low German because someone has tried, but failed, to translate a High German

original into Low German” (Hasty, Hardin, 1995, p. 196). The second one “celebrates the victory

of the West-Frankish Ludwig III over the Normans at Saucourt in 881” and was found in a

French monastery (Collitz, 1910, p. 96). The “dialect is Rhenish Franconian with an admixture of

Low and Middle Franconian.” (Hasty, Hardin, 1995, p. 217). The third one was composed in the

Bavarian area around 870 and it is a mixture of christian and pagan traditions and figures. The

beginning and the last part are missing, while the central part of the poem is the only remaining

piece. Although there is not a strict linguistic homogeneity, both lays can be considered part of

Old High German literary sources.

28

The Nibelungenlied, one of the most important literary texts in Middle High German, is a

heroic poem written between 1190 and 1200, “it is handed down in thirty variants, partly

complete and partly incomplete and written in an area between the cities Passau and Vienna”

(Collitz, 1910, p. 147). Der arme Heinrich is a narrative poem written by Hartmann von Aue. The

poem tells the story of a knight condemned by God to suffer with leprosy, who can save himself

with the blood of a virgin.

For both Old High German and Middle High German, I looked at the examples of the

present perfect, taking also into consideration the specific verse or stanza where I found them.

This procedure allowed discerning between the usages of the present perfect in direct speech from

the forms used in narration. The focus on the forms used in the narrative parts were particularly

useful to gain a better understanding of the function of this tense in its early stages of

development.

As already stated for the analysis in Modern German, I am aware that the texts that I

choose cannot offer a comprehensive view of the usage of such tenses in German today. Like the

articles from Der Spiegel, they offer a closer look at the function and meaning of the present

perfect, but also here, more texts need to be included if we want to get a bigger picture of this

topic.

In conclusion, the corpus included here could be considered as the basis for further

research on the present perfect and an example of the methodology that could be used to enrich

the number of instances for additional studies.

29

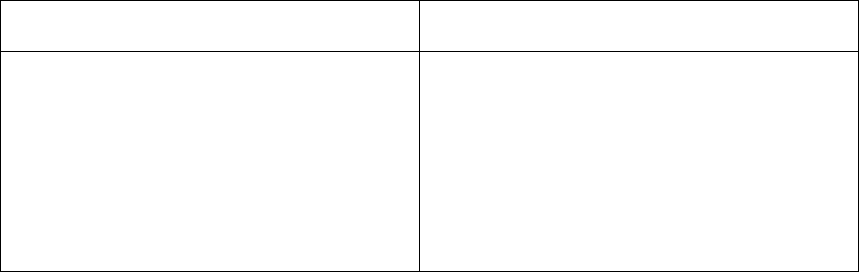

CHAPTER 4. THE PRESENT PERFECT IN MODERN GERMAN

This chapter focuses on the use of the present perfect in Modern German using authentic

written texts. The data collected in this section come from 25 articles of Der Spiegel from

November 2013, and refer to the usage of both present perfect and simple past in written

language. In these articles, I was able to find 198 forms of the first and 516 of the latter. Although

the number of simple past forms is definitely higher than the number of forms of the present

perfect, the distributions of them throughout the articles was considerably varied, as shown in the

table below:

Table 1: The distribution of present perfect and past simple, examples from 5 articles

Article title

Preterite

Present Perfect

Ein Profi für Runde zwei

28

11

Brennende Unterhosen

12

7

Pik ohne zwei

12

9

Machtprobe

10

13

Der emotionale Kurzschluss

6

13

30

The table shows a relative equal distribution of both tenses in the articles. Some of them have a

majority of preterite forms, while others contain more present perfect forms. The number of

present perfect forms found here contradicts the description of this tense in the didactic material

analyzed in the first chapter, which defines it as the tense used in spoken German. It seems that

there are some gaps between the use of this tense and how textbooks and didactic grammars

describe it.

I focused on an article in particular, Herr Meinhardt ist frei (Mister Meinhardt is free), in

order to gain insight into the usage of the present perfect in written German. The article addresses

the topic of the right-wing conservative politician Patrick Meinhardt at the end of his carrier, after

his party lost the election Baden-Württemberg. The following text is an excerpt from the first part

of the article:

(1) „Es ist seine eigene Wahlparty, auf der das Leben von Patrick Meinhardt für drei Sekunden

zum Stillstand kommt. Er steht mit verschränkten Armen in einem Hotel in Karlsruhe und wartet

zusammen mit seinen Gästen aus der Partei auf die erste Hochrechnung. "4,5 Prozent für die

FDP", sagt die Moderation vom ZDF. Meinhardt weiß, dass das der Moment ist, in dem alles aus

dem Gleis springt. Er ist bildungspolitischer Sprecher der FDP und seit acht Jahren Mitglied des

Bundestags. Auf der Landesliste Baden-Württemberg steht er auf Platz neun. 7,2 Prozent hätte

seine Partei für ihn erreichen müssen. Sein Kopf ist rot, er schwitzt, niemand im Raum rührt sich,

bis einer sagt: "Mein lieber Gott!" Meinhardt sucht die Blicke der anderen. Fünf Kilo hat er im

Wahlkampf gelassen, seit Juni ist er pausenlos unterwegs gewesen, 22!000 Kilometer durch

seinen Wahlkreis Karlsruhe-Land gefahren, alles mit Bus und Bahn, denn er hat keinen

Führerschein. 22!000 Kilometer ist einmal um die halbe Welt. 11!500 Postkarten hat er

verschickt, noch am Vortag stand er an den FDP-Ständen von sechs Städten und verteilte 300

Bananen mit den Worten: "Darf ich Ihnen ein bisschen Energie geben?", immer getragen von der

Hoffnung, er könne es noch schaffen.“ This part contains 17 present forms, 2 simple past forms

31

and 4 present perfect forms. The whole article has in total 201 present tenses, 25 present perfect

tenses and 81 simple past tenses. The distribution of these forms throughout the article also

allowed the identification of particular sections: in some of them, the author uses a high number

of preterite forms. In others, there is a majority of present and present perfect tenses. The parts of

the article are broken down below according to their tense distribution:

Part 1:

(2) „Es ist seine einige Wahlparty, auf der das Leben von Patrick Meinhardt für drei Sekunden

zum Stillstand kommt. Es steht mit verschränkten Armen in einem Hotel in Karlsruhe und wartet

zusammen…“.

Präsens: 91 - Präteritum: 2 - Perfekt: 8

Part 2:

(3) „Meinhardt wurde 1966 als uneheliches Kind geboren, er wuchs bei seiner Oma auf, in einer

billiger Wohnung, an einer der teuersten Straßen von Baden-Baden…“.

Präsens: 6 - Präteritum: 28 - Perfekt: 2

Part 3:

(4) “Welche Funktionen könnte sie heute noch haben? Von einem Politiker wie Meinhardt, der

als persönliche Bilanz nicht mehr zu bieten hat, ist keine überzeugende Antwort zu erwarten“.

Part 4:

(5) „Und Meinhardt selbst? Er begann nach dem Abitur ein Theologiestudium…“.

Präsens:0 - Präteritum: 4 - Perfekt: 0

Part 5:

(6) „Bis dahin hat er noch Zeit. Seine Idee ist, sich wieder selbstständig zu machen…

Präsens: 56 - Präteritum: 5 - Perfekt: 7”.

The five parts individuated can be distinguished not only through the types of tenses

used. If we look closer at the information included in each part, we can notice that, for example,

32

the sections with a really high number of preterite deal with the biography of the politician. Using

Weinrich’s terminology, we can say that the author is combining comment and narrative parts,

and the transition from a part to another is realized by changing from present and present perfect

to preterite. A closer analysis of the passages where the present perfect is used reveals that it is

sometimes combined together with the preterite. The following text excerpts display all the

present perfect forms found in the first portion of the article:

(7) 1. Fünf Kilo hat er im Wahlkampf gelassen, seit Juni ist er pausenlos unterwegs gewesen,

22!000 Kilometer durch seinen Wahlkreis Karlsruhe-Land gefahren, alles mit Bus und Bahn,

denn er hat keinen Führerschein. 22!000 Kilometer ist einmal um die halbe Welt. 11!500

Postkarten hat er verschickt, noch am Vortag stand er an den FDP-Ständen von sechs Städten und

verteilte 300 Bananen mit den Worten: Darf ich Ihnen ein bisschen Energie geben?", immer

getragen von der Hoffnung, er könne es noch schaffen.

(8) 2. Als die meisten seiner Gäste gegangen sind, sitzt er im Hotelgarten unter Geranien, drückt

sich ein Taschentuch über seine Tränen und sagt: "Ich mache natürlich weiter!"

(9) 3. Als hätte es diesen Abend gar nicht gegeben, an dem die FDP nach 64 Jahren aus dem

Deutschen Bundestag geflogen ist. Was lernt man daraus als Mann von der FDP? Was bedeutet

so ein Ergebnis für einen, der dafür mitverantwortlich ist?

(10) 4. Wie die meisten Politiker seiner Generation hat Meinhardt keine große Idee, an die er

glauben könnte, schon gar keine Vision, in ihm lodert auch keine politische Leidenschaft. Er hat

das Gebetsfrühstück eingerichtet, so wie andere Menschen einen Adventsbasar einrichten.

(11) 5. Die Themen, für die Meinhardt sich einsetzt, sind die, in denen es vor allem um

Chancengleichheit geht. Er selbst hat in seinem Leben davon profitiert, dass es Menschen gab,

die ihm die gleichen Chancen gaben wie anderen.

(12) 6. In der Oberstufe sammelte ein anderer Lehrer Geld, damit Meinhardt mit auf die Rom-

Fahrt konnte. In der Wahrnehmung der Bürger ist die einst liberale FDP zu einer

33

Wirtschaftspartei geworden, die sich vor allem um die Interessen einer einzelnen Gruppe

kümmerte, die des Mittelstands.

In these examples, the author combines both tenses and the change from a tense to

another seems to be related to a change of perspective concerning a particular information. In

these specific cases, the usage of the present perfect in a context with a majority of simple past

forms has the function to highlight and emphasize a certain part of the discourse. Also Alessandra

Lombardi (2008) claims that the change of tenses in German is related to a change of perspective.

Hyun-Sun Park (2009) in her work, Tempusfunktionen in Texten also argues that we express three

different intentions through tenses. In the examples listed here the author witches from one tense

to the other. Unlike what the textbooks in chapter 2 indicates about the present perfect, the change

is not related to any variation from a formal to an informal context or from a conversational to a

written mode of communication, since the examples come from the same source. The depiction

there doesn't match the usage of this tense that was observed here. Park (2009) also claims that

when the present perfect is used together with the preterite, it is because he or she wants to

emphasize the specific information stated in perfect. In the next examples, the sentences contain

preterite forms before or right after the present perfect:

(13) “Er selbst hat in seinem Leben davon profitiert, dass es Menschen gab, die ihm die gleichen

Chancen gaben wie anderen”.

(14) “In der Wahrnehmung der Bürger ist die einst liberale FDP zu einer Wirtschaftspartei

geworden, die sich vor allem um die Interessen einer einzelnen Gruppe kümmerte, die des

Mittelstands”.

(15) „. Er hat das Gebetsfrühstück eingerichtet, so wie andere Menschen einen Adventsbasar

einrichten“.

In these three sentences, the writer is highlighting the information using a different tense.

German speakers are aware of the contrast between both present perfect and preterite and use it to

34

communicate their change of perspective with regard to that particular fact or event. The most

relevant part of the discourse is stated in present perfect, while the rest is in simple past. These

sentences can be seen as a realization of the principle of contrast of which Eva Clark (1990) talks

in her work. The different attitude of the speakers in regard to a specific information, which is

considered more relevant, is expressed through the change of tenses.

The results of the analyses of the articles from Der Spiegel can be used to answer the first

question stated in the introduction to this work:

How is the present perfect used in Modern German written texts?

The present perfect can be considered a tense used to comment in Weinrich’s sense, and speakers

make specific use of tense in order to convey their speech attitude towards the information they

are communicating. Among all depictions mentioned in the second chapter, Weinrich (1964)

Welke (2011), Schumacher (2005) and Park (2009) better capture the usage of the present perfect

in Modern German, since in the examples from the articles:

• the perfect was used in a written form;

• the context was formal;

• it expressed both perfective (11, 500 Postkarten hat er verschickt) and imperfective (Er

selbst hat in seinem Leben davon profitiert) meanings.

The examples included in this section also show how pragmatics play a key role in the usage of

tense, and how the representation through Reichenbach’s parameters are unable to capture this

important aspect related to tense. The separation of grammar and pragmatics does not offer a

satisfactory approach to the meaning of tenses, since the first one determines the usage of specific

tenses in different communicative acts.

As already mentioned in the introduction to this work, a synchronic analysis is not

enough when our aim is to understand the meaning of a specific grammatical structure. It must be

combined with a diachronic study. Therefore, the next chapter deals with the historical

35

development of the present perfect and it includes examples in written texts from the early stages

of German: Old and Middle High German.

36

CHAPTER 5. THE PRESENT PERFECT IN OLD AND MIDDLE HIGH GERMAN

In the previous chapter, the analysis of written texts in Modern German show which

function the present perfect has today. German speakers use it to express their attitude in regard

to a specific information. However, as already mentioned in the introduction of this study,

synchronic data often are explained and described well in light of diachronic analyses. Therefore,

this chapter focuses on the present perfect constructions in Old and Middle High German. The

translations in this part, if no other way specified, have to be considered mine.

5.1 Old High German

The verb flection in Old High German is determined by the grammatical categories of

person (1

st

, 2

nd

and 3

rd

), number (plural or singular), tense (present and past simple) and mood

(indicative, conjunctive and imperative). There are also infinitive forms, that is, forms not

determined by person or number: the infinitive and the two participles, present and past. The past

participle is formed by adding the prefix “gi” (neman-ginoman). Some verbs already with a prefix

maintain it in the participle (firneman-finoman) while others formed the participle by changing

the stem vowel (treffan-troffan) (Bergmann-Pauly-Moulin Fankhänel, 1999 p. 31-32).

Zieglschmitd (1929), Leiss (1992), Kotin (1999), Zeman (2010) analyzed in their works the first

combinations of eigan/habên plus past participle and claimed that it has to be considered as an

adjectival structure, in which eigan/habên are full verbs with no auxiliary, like the examples

below:

37

(1) phigboum habeta sum giflanzotan in sinemo uuingarten

a fig tree has someone planted in his wine garden

‘Someone has a fig tree planted in his wine garden’

(102,2) Tatian (ca. 830)

(2) ir den christanum namus intfangan eigut

the one the name of Christ accepted has

‘The one who has the name of Christ accepted’

(Exhoratio 9,5) Tatian (ca. 830)

In the next pages the same kind of combination will be analyzed in texts mentioned in the

third chapter: Hildebrandslied, Ludwigslied and Muspilli.

In the Hildebrandslied, the poet makes frequent use of the simple past. It is used to describe past

events and it is used also in the dialogic part, where the protagonists, father and son, are talking to

each other. In this poem past participles are also used:

(3) want her do ar arme wuntane bauga, cheisuringu gitan

Whereupon he from the arm removed the ring from the emperor’s gold forged

‘Whereupon he removed the ring, forged from the emperor's gold’

Verse 33-34

(4) unti im iro lintun uttila wurtun, giwigan miti wabnum

until them their lindens little grew worn with the weapons

‘until both of the lindens little grew, all worn with weapons’

Verse: 67-68

38

In these parts, the participle forms characterize the nouns they precede or follow with a

resultative aspect, implying that “a past process brought about the state” (Slobin, 1994, p. 124).

Michael Kotin (1998) in his work about the development of the passive in German claims that

without an auxiliary the past participle exclusively denotes the substantive as a result of a finished

action or a closed process. In this lay, the past participle is used to denote a noun with a

resultative state.

In the Ludwigslied there are mainly simple past forms used in the narration and in the

dialogues. However, if this lay is compared with the first one, there are a lot of combinations that

include the past participle with uuerdhan, uusan and one with eigan (here heigan):

(5) So thaz uuarth al gendiot

When that was all completed

‘When all this had been completed’

(Verse: 9)

(6) Sume sar uerlorane Uuurdun sum erkorane

Some were lost, were some saved

‘Some were lost, some were saved’

(Verse: 13)

(7) Heigun sa Northman Harto biduuungan

Have them the Norsemen hard oppressed

‘The Norsemen have sorely oppressed them’

(Verse: 24)

(8) Sang uuas gisungan, Uuig uuas bigunnan

Song was sung fight was began

‘The song had been sung, the fight had begun’

(Verse: 48)

39

In relation to these sentences, Kotin (1999) suggests that there is no difference between

the sentences we analyzed before and the sentences listed above, in which the participles are used

in combination with these verbs. In other words, they are not auxiliaries yet at the time. The

resultative meaning of the past participle appears with and without an auxiliary, which means that

the participle keeps its original meanings in any case (Kotin, 1999, p. 82). In the sentence - Sang

was gisungan, Wig was bigunnan – there are the two forms of uuesan in the past with their

imperfective meanings and the two forms of the past participle, which give the nouns Sang and

Wig a resultative feature, collocated in the past because of the past simple forms of uuesan. Both

participle and auxiliary refer to a particular grammatical aspect, which is independent from the

other. However, the combinations of a past participle with eigan in the 24

th

verse of the lay,

seems to have a really close meaning to the present perfect in Modern German. The verb eigan

means haben (to have) and is a classified as a Präterito-Präsens, which means that the form in

present and in simple past is the same and it always has a PRESENT meaning. If eigan has a

present meaning, the past and resultative meaning of the whole structure (heigan biduuungan) is

determined by the combination of both auxiliary and past participle.

Bybee, Pekins and Pagliuca (1994) claim ”the modern perfect develops out of early

resultatives as the participle loses its adjectival nature and becomes part of the verb rather than an

adjective modifying a noun” (Bybee, Perkins, Pagliuca, 1994, p. 68) and that “a resultative

expresses the rather complex meaning that a present state exists as the result of a previous action”

(Bybee, Perkins, Pagliuca, 1994, p. 69). The connection between resultative and past, which

involves cognitive association and generalization, should represent the first step of the

development process of the German present perfect. But if the writer wanted to indicate an event

in the past, why he didn’t use the simple past, like he did in the rest of the lay? Dan Slobin in his

article “Talking Perfectly: Discourse Origin of the Present Perfect”, analyzed a similar structure

in Old English (Ic haebbe gibunden pone feond pe hi drehte) and claimed that it had two different

40

readings, an adjectival and a perfect one. The first was really similar to a report (I inform you that

the enemy is bound and in my possession), while the second was really similar to a claim and a

negotiation (It is I who captured the enemy, so give me my reward). The have + past participle

constructions contrasted back then with a preterite, which focused only on the subject’s past

agency, and not the present state of the enemy. The Old English hearer, in drawing an inference

from the possessive construction, must also have had a background knowledge of the contrasting

option of the preterite and this option must have played a role as soon as the ancestor of the

perfect contrasted with the preterite in a given speech context (Slobin, 1994, p.127).

Both adjectival und perfect readings could have been present as well in the verse of the

Ludwigslied and in a similar construction in Muspilli:

(9) Heigun sa Northman Harto biduuungan

Have them the Norsemen hard oppressed

‘The Norsemen have sorely oppressed them’

(Verse: 24)

ADJECTIVAL: The Normans have them burdened

PERFECT: The Normans have burdened them

(10) denne der paldet der gipuazzit hapet

the one can be happy that penance done has

‘Who has done penance may be happy’

(Verse 99)

ADJECTIVAL: The one, who has penance done, may be happy

PERFECT: The one who has done penance, may be happy

41

Like the Lay of Ludwig, Muspilli is written using the simple past in almost all past events

reports but in one of them we find the past participle combined with habên/eigan. In both cases

the authors were probably already aware of the pragmatic difference between past simple and the

combination of habên/eigan plus the participle.

What is relevant here, as highlighted by Slobin as well, is ‘the intent of the speaker’ in

choosing the perfect rather than the simple past. The claim reading of this construction could be

considered the original core of the German present perfect, which arose with the usage of this

construction. As Bybee claimed, citing Traugott and Dasher, “inferences arising frequently with a

construction can become part of the meaning of the construction. Given that the inference of

intention often accompanies the use of this construction, the result is that ‘intention’ becomes part

of the meaning of the construction” (Bybee, 2006, p.721).

In the early stages of the development of the German present perfect, it is possible that

both readings coexisted. However, with the repeated usage of this form, the intention of the